Dr Carole Nakhle

After several years of negotiations, Iran and six world powers reached a deal on Tehran’s nuclear programme on 14 July 2015. The deal, if respected, will create exciting dynamics in the oil and gas markets. Investing in Iran, however, will require confident planning and strong nerves.

The international community has, on balance, welcomed the deal between Iran and the six world powers. The deal would end the painful economic sanctions that have damaged the economy. From the oil and gas markets’ perspective, such a deal cannot be downplayed given Iran’s prominent position as a hydrocarbon reserves holder and producer.

How much oil and gas Iran will bring to the markets in the near future remains to be seen but the uncertainty will not stop zealous investors from chasing potential opportunities. In the end, it is the balance between risks and rewards that will determine capital commitment. The Iranian government has promised more lenient contractual terms in an attempt to lure investors but the devil remains in the detail. Iran’s ‘come back’ to the global oil and gas scene coincides with another important development: an oil price staying below US$60 per barrel, which is likely to put a premium on cooperation, especially within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Deal

The deal between Iran and the six world powers – the P5+1 of China, France, Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom, plus Germany, whereby Iran agreed to scale back its uranium enrichment programme brings Iran back into the international fold. Thousands took to Iran’s streets to celebrate the prospect of an end to the painful economic sanctions that have damaged the economy.

From the oil and gas markets perspective, the deal cannot be downplayed. Iran is an established oil and gas producer and exporter, sits on one of the world’s largest oil and gas reserves, is a member of the OPEC, and has the potential to alter existing oil and gas market dynamics. If Iran manages to ramp up its exports, then the oil price will face additional downward pressure, everything else being the same. But the oil market is global and several forces may come into play: OPEC may be forced to introduce production cuts, US oil shale production may not be able to keep up, and demand may respond positively to falling prices thereby reversing the decline.

It is unlikely that Iranian oil and gas will flood the markets overnight. It will take some time before the Iranians are fully able to unlock their hydrocarbon potential and deliver a significant quantity of additional oil and gas to international markets.

Potential

According to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Iran has the largest proved gas reserves in the world (18.2 per cent of the world total) and the fourth largest proved oil reserves (9.3 per cent), after Venezuela (17.7 per cent), Saudi Arabia (15.8 per cent) and Canada (10.3 per cent).

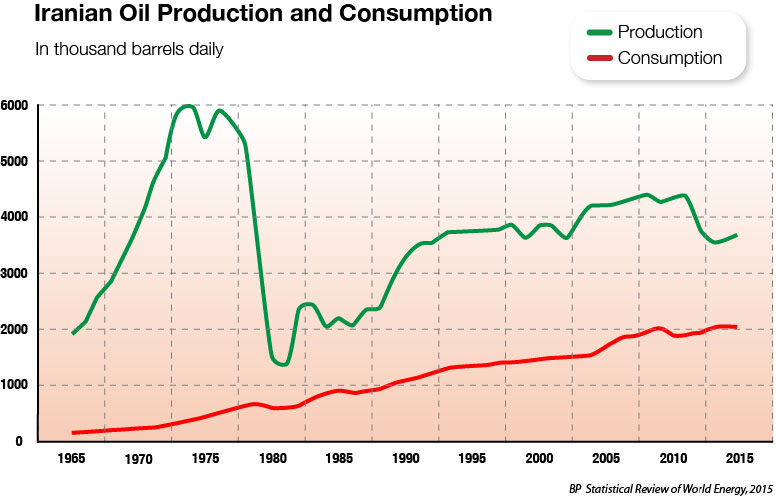

Despite the sanctions, Iran has remained a sizeable oil and gas producer.

It is the fourth largest gas producer after the US, Russia and Qatar. Despite this impressive level of production, the Iranian gas sector is underdeveloped, thereby offering sizeable investment opportunities. To date, most of the gas production has met domestic demand, with only a small supply surplus since 2012. Iran’s limited gas exports have largely targeted Turkey through the Tabriz-Ankara pipeline, then Armenia and Azerbaijan, also via pipelines. Iran could become a major gas exporter but large investment is needed first to build the necessary infrastructure for pipelines and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) exports.

Iran’s oil potential is equally important. In terms of oil production, the country ranks seventh in the world after Saudi Arabia, Russia, US, China, Canada and the United Arab Emirates. Iranian oil production reached a peak of more than 6 million barrels per day (Mb/d) in 1974 and has been in decline since because of lack of capital and technology, exacerbated by sanctions. Nonetheless, Iran produces more oil than its neighbours Iraq and Kuwait.

The international sanctions, which have targeted Iran’s energy sector since 2010, have limited Iran’s oil exports to an average of approximately 1Mb/d. There is no doubt that the lifting of the sanctions, which have almost halved Iranian oil exports, will restore some of the country’s export capacity.

Opportunity

Following the announcement of the nuclear deal, the media was full of stories about international companies, particularly European, rushing to Tehran to get in first on this large and growing market. According to the World Bank, Iran has the second largest economy after Saudi Arabia in the Middle East and North Africa.

For oil and gas companies, the prize is precious. The lifting of the sanctions has surely played a role, but an earlier development had already whet oil companies’ appetites: Iran announced it would offer investors a new contractual arrangement – the Iran Petroleum Contract (IPC).

Long before the sanctions were imposed, the Iranian constitution had restricted foreign investment in the exploration and production of oil and gas. Furthermore, prohibitive contractual terms have impeded investment. Traditionally, international companies can operate in Iran only under very restrictive contracts, called Buyback. Under this type of agreement, companies receive a fixed remuneration fee for their services, in addition to recovering some of their costs, but they are not entitled to any ownership of production. The Buyback contracts are also short term – less buy brand name accutane than ten years. The oil companies have to fund all investment costs and implement exploration and/or production operations on behalf of the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) for an agreed work programme. Once the service is ‘completed’, the NIOC takes over the project.

Further details are yet to be revealed about the new IPC, but Iranian officials have stated that these contracts would be more attractive than the Buybacks, starting with a longer term contract (20-25 years), and be more competitive than those offered by neighbouring countries. However, a cautious attitude needs to be adopted until the actual details are known.

Risks

Oil companies will have to assess whether the new contracts will be enticing enough to commit significant capital in the country. Offering more lenient contractual terms is surely an attractive feature for oil and gas companies but many complications remain.

There are many examples of oil and gas rich countries that have failed to attract sufficient investment because of a series of so-called above ground factors arising.

In Algeria, for instance, project delays caused by slow government approval, an unstable legislative and regulatory environment, protectionist policies, a tough tax regime, corruption, and high security risks have all led to the country’s disappointing production performance. This does not realise the country’s resource potential.

More recently, Mexico, which remained closed to foreign investment for 75 years, has not attracted the originally hoped international interest during its first licensing rounds in 2015 because of contractual terms deemed unattractive to investors. Despite the initial rush to Iraq following the country’s first post-war licensing rounds in 2009, some oil companies have scaled down on their investment, while others withdrew completely. The originally optimistic production targets of 12Mb/d by 2017 have now been halved.

In Iran, additional concerns have been raised about the nuclear agreements ‘snap back provisions’, whereby the US or any signatory, can reimpose sanctions in the event of a perceived violation of the deal. The legal community is yet to clarify this process and its implications on investors. However, the inclusion of such a provision increases the risk of doing business in Iran.

Price

Price

Iran’s return to the global oil and gas scene coincides with another important development: an oil price of US $60 or less, compared to the previous highs of more than US $100 between 2011 up until mid-2014. Such a fall has been blamed on the additional supplies coming from North America – largely thanks to the shale revolution, a weaker than expected global demand and the reluctance of OPEC to implement any production cuts.

Scenarios

Rapid ramping up unlikely

Should Iran restore its pre-sanctions exports and increase its production further under such circumstances, the oil price is likely to come under additional pressure. Consuming countries will surely welcome such an outcome, although tackling the green agenda might become more challenging.

It would be premature, however, to predict that the oil and gas markets will be immediately flooded with new Iranian supplies. Many technical and legislative bottlenecks remain. The sanctions will not be lifted overnight; it will be a gradual and probably lengthy process, especially for American sanctions, which might easily take two years to be removed in full. Experience in Iraq, Libya and Venezuela also shows that many oil-producing countries that faced domestic unrest struggled to increase their production to pre-crisis level. Even if Iran is technically able to increase its production drastically, the country is restricted by OPEC’s quota policy. Given the current oil price realities, there will be a premium on co-operation especially within OPEC.

New investors to take their time

As for oil companies, risks are an inherent feature of their business. Initiating talks with the host government while the situation is still unfolding is also typical. After all, dedicating one or two years for that is marginal in an industry where a project’s life can easily exceed 30-40 years. Oil majors such as Total, Eni and Shell are showing renewed interest in Iran but many companies are remaining cagey about their involvement.

For more than a century, oil companies have had to peer through various risky ventures and political circumstances, especially in the Middle East, and take a view of prospects years or even decades ahead. Committing substantial capital in Iran today will, however, require a considered approach and patience.

FACTBOX

- Iran’s oil industry was nationalised in 1951. Following the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and until 1995, there was no direct foreign participation in Iran’s upstream oil sector.

- The giant South Pars gas field, Iran’s and the world’s largest gas field, includes over 27 per cent of Iran’s total proved natural gas reserves.

- The oil sector is dominated and managed by the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC). The National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) is responsible for natural gas infrastructure, transportation, and distribution.

- China is Iran’s largest trading partner and biggest oil importer.

- Armenia exports electricity to Iran to compensate for the natural gas volumes it receives, while Azerbaijan repays Iran for the gas sent to its Nakhchivan exclave by exporting similar volumes to North-Eastern Iran (Energy Information Administration, EIA).

- The World Bank ranks Iran 130 (out of 189 economies) in its Doing Business 2015 report.

- Around 56 per cent and 97 per cent of Iranian oil and gas respectively are consumed domestically.

- Since 2010, Iran has reduced its energy subsidies – a move described by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as exemplary.

Article Reproduced with the kind permission of Geopolitical Intelligence Services

The article was first published on 20 August 2015