Dr Carole Nakhle

India, the world’s largest democracy, is increasingly asserting its influence on global energy and climate change discussions. With an expanding economy, a growing population and an increasing dependence on fossil fuels, particularly coal, India’s energy policies and consumption are being watched closely by world leaders and energy experts.

India is set to overtake China as the world’s most populous country by 2030. A large and growing population, combined with rapid economic growth, translates into a higher demand for energy. India’s new Prime Minister Narendra Modi is pursuing the agenda of the previous government albeit more aggressively. Mr Modi’s priority is to revive the economy, eradicate poverty and provide access to electricity to all Indians by 2022. Despite the government’s aim to become self-sufficient, experts expect India to become increasingly dependent on imported energy, raising domestic concerns about security of supply. India’s largest energy source is coal, the main culprit behind the country’s rank as the third largest CO2 emitter in the world, after China and United States. If India pursues its economic growth targets, it is expected to have the world’s highest growth in energy demand by 2035.

INDIA is set to overtake China as the world’s most populous country by 2030. It has nearly 1.3 billion inhabitants increasing by 1.3-1.6 per cent annually. A large and growing population, combined with an expanding economy, translates into a higher demand for energy: More people with larger incomes mean an increase in energy consumption. As described by the Indian government, ‘for a growing economy, large doses of energy are a must to maintain a high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate.’

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is pursuing the agenda of the previous government – albeit more aggressively. Mr Modi’s priority is to revive the economy, eradicate poverty and provide all Indians access to electricity by 2022.

Policy logjam

These are ambitious targets but in line with the country’s 12th Five Year Plan (2012-2017) ‘Faster, More Inclusive and Sustainable Growth’, whereby the Indian government has set a target of eight per cent economic growth for that period. A failure to achieve that target has been described as ‘policy logjam’ resulting in a growth of five to 5.4 per cent.

India is the tenth largest economy in the world after the United States, China, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Italy and Russia. According to official studies, if India achieves an average annual GDP growth rate of 7.4 per cent, it would be the third largest economy in the world, after China and the US, by 2047.

After growing at an average eight per cent over the period 2007-2011, India’s GDP decelerated to below five per cent in 2014, the lowest level in a decade, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The Fund describes such a slowdown as ‘unusual among emerging markets in its severity’.

Slowdown

The Indian economy has been affected by the slowdown in other economies. Domestic factors, such as supply bottlenecks, delayed project approval and implementation, and heightened policy uncertainty, have played an equally important role.

The outlook for the economy looks brighter under the new government, which, so far, has boosted investors’ confidence. Goldman Sachs predicts a 6.3 per cent economic growth for 2015, with India outperforming other emerging markets. The growth is supported by declining commodity prices particularly oil, contributing to inflation control. India’s import bill for crude oil reached US$160 billion in 2013, when the oil price averaged US$111 per barrel. As the price dropped to less than US$60 per barrel, the import bill will halve.

India’s economic outlook can be improved further if the government continues its reforms over energy subsidies and price, as part of its wider new policy agenda, including cutting red tape, liberalising markets and encouraging competition. Fuel subsidies and regulated prices have traditionally encouraged wasteful consumption and hindered investment.

Consumption

Economic growth and energy consumption are intertwined in India, hence the central importance of security of supply – that is, the availability, reliability and affordability of energy resources. As put by the Indian government, ‘The term energy security has a large connotation for the country including economic stability and ensuring well-being of the people of the country.’

The government aims to achieve self-sufficiency to reduce its exposure to supply disruptions elsewhere. Experts, however, expect India to become increasingly dependent on energy imports. Although domestic production will increase, it will be outpaced by the growing demand. According to BP World Energy Outlook, by 2035, India’s natural gas imports will rise by 573 per cent, oil imports by 169 per cent, and coal by 85 per cent.

While import dependence can worsen the balance of payment and deplete foreign exchange reserves, especially at periods of high energy prices, it is not necessarily a threat to security of supply; a dependence only on domestic supplies does not guarantee secure supplies either. Energy security can be achieved through several means, mainly the diversification of energy resources and sources, and improvement in energy efficiency.

Energy needs

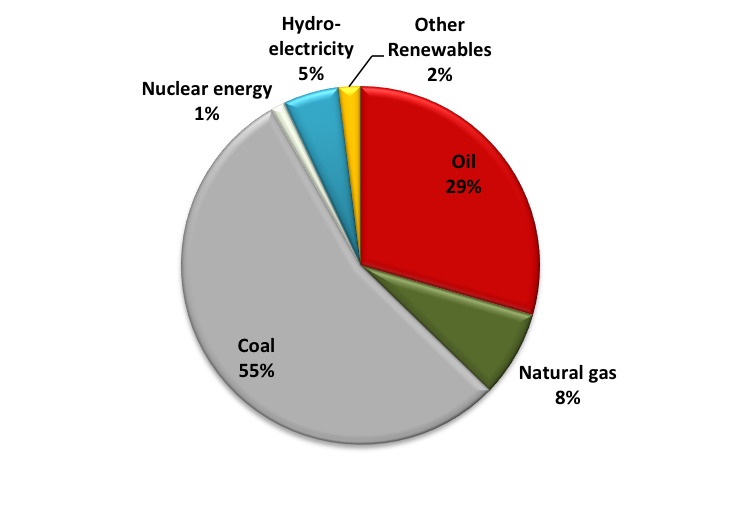

India’s largest energy source is coal, followed by oil and natural gas which, together, meet almost 92 per cent of the country’s total energy needs. The rest is from hydropower, traditional biomass and waste.

Coal is also the main fuel for electricity production, accounting for more than 71 per cent. In 2013, India saw its second largest volumetric increase in coal consumption on record.

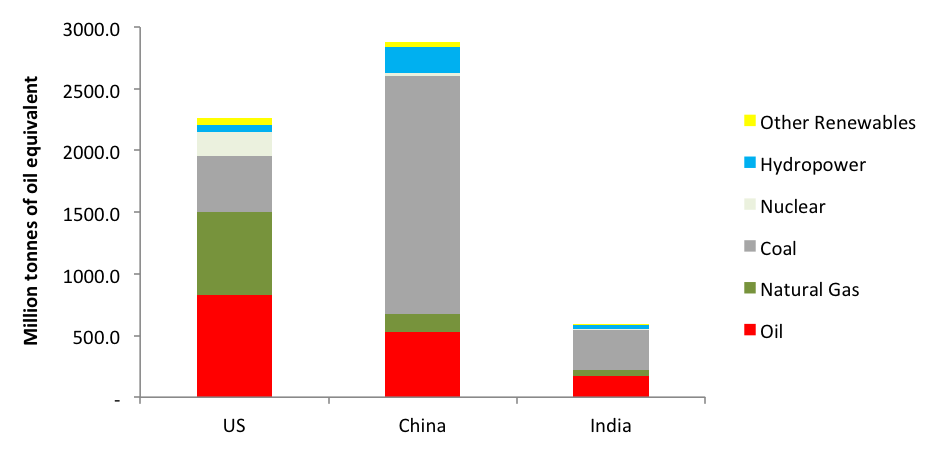

With an 8.5 per cent share of the world’s total consumption, it is the third largest consumer of coal after China (50 per cent) and the US (12 per cent).

India has the fifth largest coal reserves in the world (6.8 per cent), after the US, China, Russia and Australia, and is also the world’s fifth largest producer (almost 6 per cent), after China (48 per cent), US (13 per cent), Australia (7 per cent) and Indonesia (7 per cent).

In 2013, India displaced Norway to become the fifth largest global hydropower producer after China, Canada, Brazil, US and Russia. The monsoon season, however, has a direct correlation with hydropower generation; a drought or weak monsoon season leads to a fall in hydropower generation with the coal power plants balancing the system.

Renewables

Despite the government’s effort to diversify its sources of energy mainly by increasing the share of renewables (wind and solar), and its desire to make India the world’s largest destination for renewable energy, experts expect the country’s energy mix to evolve buy accutane online very slowly over the next 20 years, with fossil fuels accounting for 87 per cent of demand by 2035.

India’s primary energy mix: Experts expect it to evolve very slowly over the next 20 years

(BP Statistical review 2014)

(BP Statistical review 2014)

The dominance of fossil fuels, in particular coal, is the main culprit behind India’s rank as the third largest carbon emitter in the world, after China and United States.

The country’s energy-related emissions are set to more than double by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and confirmed by India’s environmental minister, Prakash Javadekar, who said at the UN Climate Summit in 2014 that carbon emissions were expected to continue to rise for the next 30 years.

India is the world’s fourth largest primary energy consumer after China, US and Russia. The country’s per capita energy consumption is only one-third of the global average while its electric power consumption per capita is 684 kWh per day, compared with China (3,298 kWh) and the United States (13,246 kWh). It is therefore not surprising to see that if India pursues its economic growth targets, it is expected to have the highest growth in energy demand by 2035.

Carbon emissions

This can of course be bad news for the control of carbon emissions especially if India’s consumption of fossil fuels increases accordingly. However, India is unlikely to agree to put limits on its carbon emissions at the expense of its economic growth. The country’s per capita GDP is significantly below China’s and a long way off the US’s.

India’s position vis-a-vis curbing carbon emissions is in line with that of many developing countries who often refer to ‘the moral principle of historic responsibility’ – developed economies, chiefly the US, which spent the last century building their economies while pumping emissions into the atmosphere, should bear the greatest responsibility for cutting carbon emissions.

India’s share of global carbon emissions (5.5 per cent) remains very small compared with China (27 per cent) and the US (17 per cent), especially if taken on a per capita basis.

The increase in India’s income may not necessarily translate into faster growth of energy, on a per capita basis. The answer depends on energy intensity, which is a broad measure of energy per unit of GDP, therefore indicating energy efficiency.

China, India and the US: Primary energy consumption in 2013

(BP Statistical review 2014)

Economic growth

A decline in energy intensity restrains the overall growth of primary energy: The less energy an economy needs to produce one unit of GDP, the more efficient the system is, and the more economic growth can be fuelled with the same amount of energy.

The Indian government has long declared its intention to enhance energy intensity by 20–25 per cent by 2020. Currently, India’s primary energy efficiency is lower than the average of non-OECD countries.

Improvements in energy efficiency largely depend on prices and technology, which in turn requires a competitive market structure. Economies where markets do not allow prices to play a guiding function for energy use are very energy inefficient. Technology, typically driven by competition, allows leapfrogging: An economy which industrialises late does not replicate the technology of earlier periods; it simply uses the latest technology.

Scenarios identified

In its India Energy Security Scenarios 2047, the government has identified four for its energy future:

- ‘The least effort’ – the most pessimistic, passive scenario assuming little or no effort made in terms of interventions on the demand and the supply side

- ‘The determined effort’, which describes the level of effort deemed most achievable by the implementation of current policies

- ‘The aggressive effort’, which reflects the level of effort needing hard but deliverable change, and

- ‘The heroic effort’, the most optimistic which considers aggressive changes that push towards the physical and technical limits of what can be achieved.

Under the least effort scenario, by 2047, import dependence will rise to 84.5 per cent, carbon emissions per capita will increase from 1.4 tonnes to 7.7 tonnes per capita as the share of coal increases to 61 per cent of the primary energy mix while the share of renewables remain at four to five per cent.

By contrast, in the heroic effort scenario, the import dependence falls to 21 per cent, emissions per capita increase to 3.35 tonnes, coal’s share decreases to 42 per cent and renewables increase to 29 per cent.

The answer is likely to lie within those two extremes: the Indian government is already taking action to tackle its energy needs in a more sustainable way but ‘the heroic scenario’ is too ambitious and costly.

India will increasingly become an attractive destination for international capital. As put by the Power and Coal Minister Piyush Goyal, ‘energy is one sector where there is lot of excitement and interest that I am seeing from across the world.’

India energy

- The National Democratic Alliance government led by Narendra Modi won the 2014 general election. Mr Modi replaced Manmohan Singh as the new Indian Prime Minister

- India’s population was 350 million when it gained independence in 1947. Today it is 1.27 billion

- 40% of households lack access to electricity while electrified areas suffer from rolling electricity blackouts

- India and China will account for about half the world’s growth in energy demand by 2040

- India is the fourth largest oil consumer in the world, after the US, China and Japan

- India is heavily dependent on coal imports from Australia, Indonesia, South Africa and Canada, and the Middle East, mainly Saudi Arabia for oil and Qatar for Liquefied natural gas (LNG)

- Dependence on energy imports has been hovering at nearly 35%of annual demand over the last decade

- Around US$250 billion will be invested in the electricity and renewable sector by 2019

- India intends to increase its solar capacity to 100 GW by 2022

- India has emerged as a regional refining hub. With an oil refinery capacity of 4,319,000 barrels per day, it was the second largest oil refiner in the Asia Pacific after China, in 2013, and ranked fourth worldwide after the US, China and Russia

- PM Modi recently announced that the nationalised coal industry would be opened to allow private firms to compete with Coal India, which accounts for 80% of the country’s output

- On 25 January 2015, The White House announced a five-year Memorandum of Understanding on Energy Security, Clean Energy and Climate Change between India and the US. The two countries cooperate on several energy projects, including the US-India Partnership to Advance Clean Energy (PACE), a five-year initiative to enhance energy efficiency and promote clean energy in India, and Unconventional Natural Gas Cooperation under the auspices of the Global Shale Gas Initiative (GSGI)

Article Reproduced with the kind permission of Geopolitical Intelligence Services