Dr Carole Nakhle

Iraq has emerged as the most recalcitrant member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), hampering the group’s attempts to cut oil production and push prices up. Stressing disparities in production data and pointing to its burdensome fight against insurgent forces, Iraq is resisting any output reductions.

The enthusiasm following the September 2016 informal OPEC gathering in Algiers is rapidly fading. At that meeting the organization agreed to reduce production, sending a signal to the market that it could still act coherently. Earlier attempts to reach a deal on freezing or reducing output in February and April had failed, primarily because of disagreements between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

In Algiers, those differences were set aside and Iran was exempted from any cuts, at least until it restores production to pre-sanctions levels. Libya and Nigeria were also given exemptions because domestic political unrest has significantly constrained their production capacity. By the same logic, Iraq argued that it should also be shielded from any output cuts because of its ongoing war against Daesh (also known as Islamic State or ISIS).

Iraq is a founding member of OPEC. Its quota and Iran’s were set at equal levels after the war between the two countries ended in 1988. That arrangement was short-lived, however. Iraq has not participated in OPEC’s quota system since its 1990 invasion of Kuwait. In 1998, it was given an exemption to allow it to recover from years of sanctions and conflict.

Prior to the collapse of the oil price in the summer of 2014, Iraq toyed with the idea of rejoining the quota system. Doing so would have been conditional on it reaching a certain level of production. Back in August 2010, then Iraqi Oil Minister Hussain al-Shahristani said that his country would consider abiding by OPEC quotas once production rose to at least 4 million barrels a day (Mb/d). He later revised that figure to 5 Mb/d.

Statistical disparities

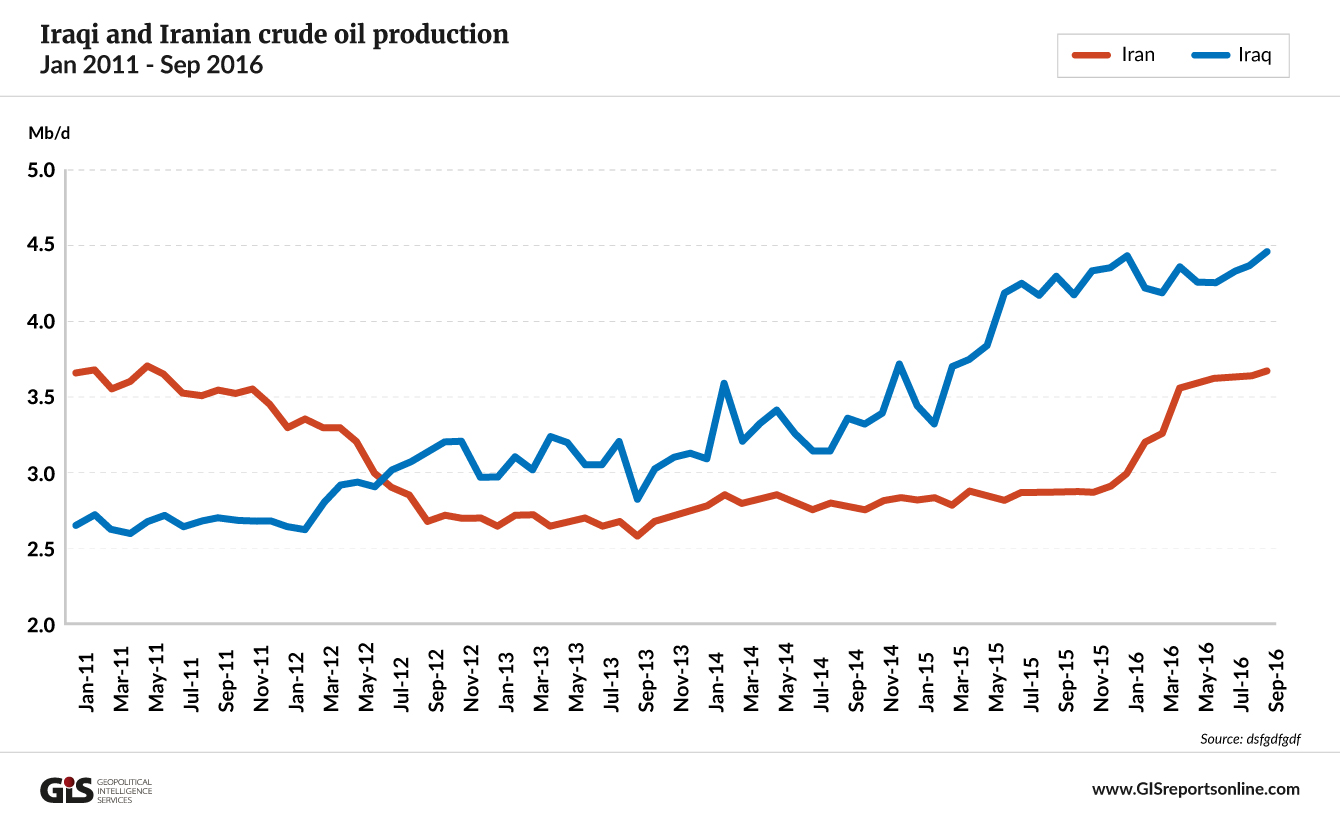

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Iraq’s oil production reached a record high of 4.46 Mb/d in October 2016. This includes output from the Kurdistan Region and well exceeds the country’s previous peak of 3.5 Mb/d, achieved back in 1979.

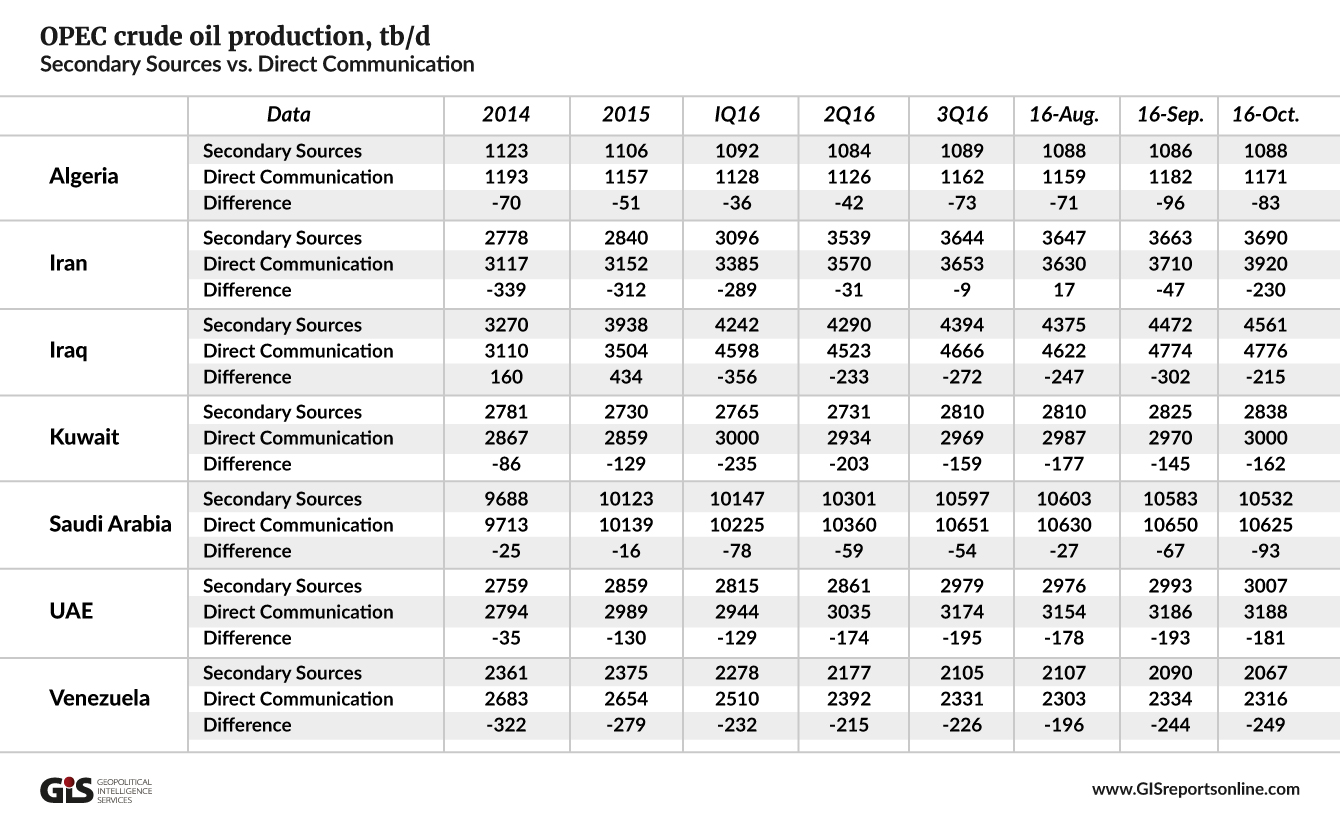

But Iraq has questioned the accuracy of third party data sources such as the IEA, which, according to the country’s current Oil Minister Jabbar al-Luaibi, significantly underestimate the country’s capacity. These so-called “secondary sources” provide one of the two sets of production data that OPEC includes in its regular publications and that are compiled from external sources such as news agencies and intergovernmental institutions. They are considered a more accurate reflection of output. The other data source, known as “direct communication,” is based on submissions from the individual members themselves.

Disparities in figures from the two sources are common. The secondary sources tend to be more conservative than the direct communication. For Iraq, that difference has been particularly pronounced throughout 2016, amounting to several hundred thousand barrels per day. In September, the disparity exceeded 300,000 barrels per day – nearly half the proposed production cut that OPEC announced in Algiers. Iraq’s complaints are echoed by Iran and Venezuela, which argued that the self-reported numbers should form the basis for allocating production cuts. If the secondary data is used, these countries would be allowed to produce much less.

Following the meeting in Algiers, SOMO, Iraq’s national oil marketing company, released detailed data on oil production and exports from each of the 26 oil fields it controls – instead of the total production figure it usually releases. It also included a single output figure for the semiautonomous Kurdish region. The aim was to show that the secondary sources OPEC uses are inaccurate.

Following the meeting in Algiers, SOMO, Iraq’s national oil marketing company, released detailed data on oil production and exports from each of the 26 oil fields it controls – instead of the total production figure it usually releases. It also included a single output figure for the semiautonomous Kurdish region. The aim was to show that the secondary sources OPEC uses are inaccurate.

The discrepancies in the data appear to result from Kurdish production figures. According to Bloomberg, Kurdish oil production was 290,000 barrels per day lower in September 2016 than what the federal government reported for the region. SOMO appears to have double-counted production from two Kurdish fields.

Daesh dilemma

While most observers thought Iran would present the chief obstacle to OPEC reaching a deal, Iraq has emerged as the real challenge. All along, Iraq has supported introducing production cuts to drive up oil prices. Its economy depends heavily on oil, which provides around 90 percent of state revenues. According to the World Bank, the fall in oil prices left Iraq with about $35 billion less oil income in 2015 buy accutane 40 mg online than in 2014. This drove the country’s budget deficit to unsustainable levels.

The situation has been exacerbated by the Daesh insurgency, which began to gain momentum in early 2014, only a few months before the oil price collapsed. On top of huge expenditures on military operations to fight the insurgents, Iraq must also support more than 4 million displaced people, reconstruct liberated areas and repair infrastructure – including oil fields that Daesh set on fire.

Increasing oil production in 2015, even at lower prices, helped sustain the economy, especially because the non-oil sector has contracted significantly. Maintaining oil production at its current levels is crucial for Iraq. Its reluctance to join other OPEC members in cutting output is unsurprising, even as it waits for other members, mainly countries like Saudi Arabia that have recently seen their market share expand significantly, to take the lead.

Mr. al-Luaibi was quoted saying that if it weren’t for the war with Daesh, Iraq would be pumping out 9 Mb/d. He added that the country had lost market share to other producers as a result of the conflict. However, it is unlikely that Iraq would have been able to ramp up output so quickly, especially amid lower capital spending and infrastructure bottlenecks. Investment in storage and export infrastructure is needed to facilitate production growth. Even the more realistic target of 6 Mb/d by 2020 may be too ambitious under current circumstances.

Notwithstanding Mr. al-Luaibi’s comments, Iraq has enjoyed the biggest expansion of market share in OPEC: from just under 8 percent in 2011 to more than 10 percent in 2015. This increase has come at the expense of other members, particularly Iran, which lost more than 2 percent over the same period. Between 2011 and 2015, when international sanctions targeted Iran’s energy sector and curtailed its exports, Iraq gained much of what Iran lost. During that period, Iraq’s oil production exceeded Iran’s for the first time in almost two decades. Some observers contend that Iraq and Iran want to increase their combined slice of the pie to the point where it equals Saudi Arabia’s, thereby gaining a stronger voice within OPEC.

Saudi sacrifice

Back in 2010, Mr. al-Shahristani said Iraq would not produce more oil than the market can absorb and force the price of oil down. Today, it seems to be doing exactly the opposite, trying to expand its market share at the expense of maximizing government revenue. Iraq’s oil production has surged, recording the world’s biggest annual increase of 23 percent in 2015, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

The war on Daesh may justify exempting Iraq from OPEC cuts, but the Iraqi army has made progress recently, retaking the cities and the oil fields that were under Daesh control. Hopes are rising that the war is nearing an end, though the security risk will remain high. Other OPEC members who have committed to production cuts either face domestic unrest (Venezuela) or additional military expenses (the Gulf states) at a time when they all confront the troubling implications of lower oil prices. In this sense, Iraq is no exception.

In economic terms, the wounds have been largely self-inflicted. Iraq’s economy experienced serious challenges even when oil prices were high because of its ineffective institutions and high levels of corruption, which discouraged investment. Iraq scores poorly when it comes to the ease of doing business (165 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s ranking) and corruption (161 out of 168 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index).

These shortcomings make it difficult for Iraq to make a convincing case for concessions from OPEC. If it persuades the organization to use its self-reported production figures, other members, including Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela, can make the same argument. That would render the organization’s reduction target of between 240,000 and 740,000 barrels per day rather meaningless. Conditions on the global market make the situation worse. There is plenty of non-OPEC supply, shale oil production may rebound, demand is weaker than expected and inventories are full.

OPEC will therefore have to consider a bigger output cut. This is only possible if other countries, led by Saudi Arabia, are willing to carry that burden, sacrificing their own market share to allow other members to expand theirs.

The article was first published on Geopolitical Intelligence Services