Dr Carole Nakhle

In 1938, Mexico became one of the first countries in the world to nationalize its oil industry. Until 2013, it remained one of the few countries – and the only member of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – to close its upstream oil and gas sector to private international investment. With a leftist ruling party that monopolized the political scene for more than seven decades, Mexico stood out among its peers when it cut oil production in 1998, together with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), in an attempt to stop the decline in prices.

However, Mexico broke with these long-standing policies three years ago, when a sweeping overhaul of the energy industry was approved as part of a wider government program of economic and social reforms. The constitutional changes ended the 75-year monopoly enjoyed by the state oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), and opened the sector to international oil companies.

The government hopes that these reforms will modernize its oil and gas industry and help stabilize and then reverse a steep fall in domestic oil production. The authorities have moved fast, as several licensing rounds to auction oil and gas blocks were announced in 2015 –with mixed results. Several risks to the reform process remain and it is unlikely that Mexico will return to the output levels of its pre-peak heyday anytime soon.

Reform drivers

In oil-dependent economies, reforms are often triggered by a sharp decline in global prices. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 development strategy is a prime example. Mexico appears to be somewhat of an exception to this rule, as its reforms were announced when oil prices were around $100 per barrel.

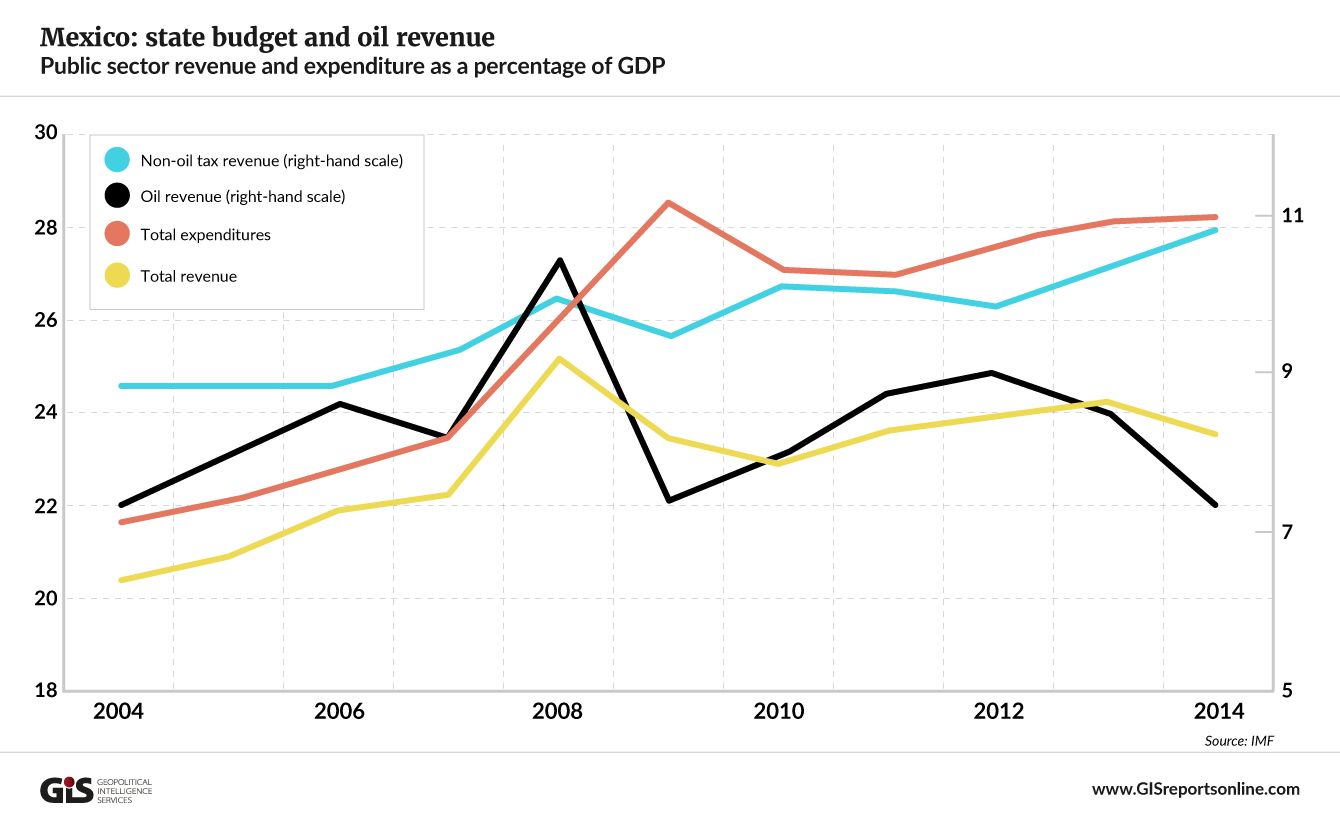

One can argue that the country’s economy is more diversified than many of its peers, making the price of crude a less powerful trigger. Nevertheless, the country remains the world’s 12th-largest producer and oil revenue is a vital component of the state budget, with Pemex funding one-fifth of all expenditures. Furthermore, the decline in oil production over the past decade or more has outweighed any benefits derived from higher prices, and has exacerbated the implications of their decline in recent years.

Mexico’s oil production peaked in 2004 at 3.8 million barrels a day (Mb/d). The country was then the third-largest non-OPEC producer after Russia and the United States. Output has been declining ever since. In 2015, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Mexico recorded the largest decrease in production, losing 200,000 b/d from the previous year to reach 2.6 Mb/d, 33 percent below its peak. Although domestic oil consumption fell between 2013 and 2015 after steadily rising for many years, output dropped even faster – declining 7 percent compared with a less than 1 percent fall in consumption.

The result has been a shrinking export capacity. According to a November 2015 assessment by the International Monetary Fund, shrinking domestic oil production continues to be a drag on the economy, knocking approximately one-quarter of a percentage point off the country’s growth rate in 2015.

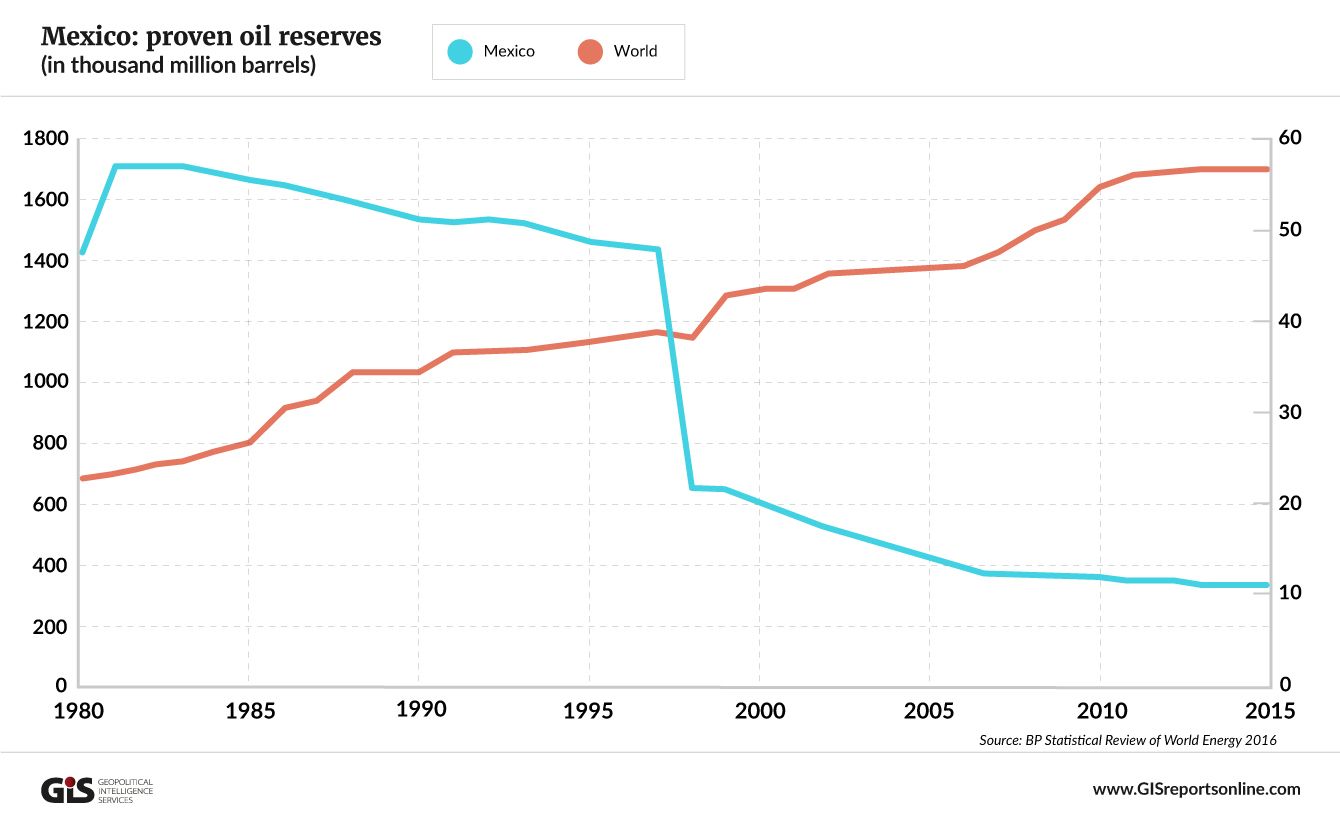

What is more astonishing is the shrinking reserves base, where Mexico has moved in the opposite direction from the rest of the world. Globally, proven oil reserves increased by 22 percent between 2005 and 2015. In Mexico, they declined by 21 percent over the same period. That does not mean Mexico is running out of oil; proven oil reserves are as much a function of economics as of geology. They grow as a result of new discoveries and technological progress.

Neither exploration nor innovation has been a strong point of Pemex, Mexico’s biggest company and a textbook example of the inefficiencies of state ownership. The pre-2013 constitutional arrangement shielded Pemex from the competitive pressures that typically induce efficiency in a company’s operating practices, while denying it access to advanced technologies through partnerships with international oil companies.

Pemex’s finances have been in dire condition with an unsustainable level of debt and a bloated workforce, in addition to a large tax bill making it the largest contributor to the state budget. These factors, in addition to political interference among others, have severely hindered Pemex’s ability to invest efficiently to safeguard and expand its production capacity. Some experts consider the company to be a hopeless case; in 2013, The Economist described Pemex as “unfixable” despite the government’s reforms and urged its full privatization instead.

National pride

Pemex’s problems did not emerge recently; they have been ongoing for at least two decades. The government tried to address them by making some changes back in the 1990s, and then again in 2008 following the financial crisis. Such tinkering was not enough, however, because it failed to address the underlying problem: Pemex’s monopoly on upstream operations.

Whatever its inefficiencies, Pemex is considered to be a source of national pride. Public sentiment remains strongly in favor of national ownership of Mexico’s oil, which for many years blocked any drastic reforms that could jeopardize Pemex’s monopoly.

Several factors have contributed to weakening this mindset. Chief among them was the breakup of the political monopoly wielded by Mexico’s ruling party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which lost its first election in more than 70 years in 2000. This reinforced a conviction, even with the party’s own ranks, that the old order needed to change. Ahead of the 2012 presidential election, the PRI’s candidate Enrique Pena Nieto promised to reform the hydrocarbon sector through constitutional changes, a pledge he fulfilled after winning the vote.

Apart from local conditions, the shale revolution that started right at Mexico’s doorstep simply meant that international competition was getting tougher. The U.S. is the largest market for Mexico’s crude oil exports, but its need for external supplies has diminished greatly with the development of domestic shale output. This has negatively affected Mexico’s already shrinking oil revenue.

Investment opportunities

For decades, Pemex has plucked the low-hanging fruit, relying on production from existing, easily accessible fields, both onshore and in shallow coastal waters. But many of these deposits, like the crown jewel Cantarell field that has fed Mexico’s exports since the 1970s, are now mature and in the declining stage of their production cycles. In such fields, significant investment is required to enhance oil recovery and extend their productive life.

Investment opportunities also abound in exploration, especially in the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. side of the Gulf is crowded, with more than 70 international oil companies drilling hundreds of wells every year in deepwater and ultra-deepwater fields. The Mexican side is much quieter, with Pemex drilling only a handful of wells while shying away from deepwater deposits and the Gulf’s more complex geologies.

As for unconventional resources, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) ranks Mexico as having the sixth-largest amount of technically recoverable shale gas in the world (after China, Argentina, Algeria, the U.S. and Canada) and the eighth-largest reserves of shale oil (after Russia, the U.S., China, Argentina, Libya, Australia and Venezuela). These resources, like deepwater deposits, require technology, know-how and capital to develop. Pemex has minimal technical expertise in both areas, let alone the capital needed to exploit them.

Auction process

The government kicked off its reform package in March 2014 with Round Zero (Rondo Cero), which gave Pemex the opportunity to inform regulators which fields it wished to retain for its own exploration or development.

After that, the sector was opened to outside competition in three auctions. The government awarded contracts to international companies between July and December 2015 for different types of fields – onshore and offshore, under exploration and in production.

The outcome of the first auction fell well short of the government’s expectations: only two of 14 shallow-water exploration blocks were awarded, and the winning consortium did not include a major oil company. The second auction went better, after the government relaxed the bidding terms and clarified some contractual ambiguities. Three of the five shallow-water production blocks on offer were awarded, one of them involving a contract with the Italian major Eni.

The third auction was even more successful. Twenty-five onshore blocks for producing fields were offered and 51 companies, mostly Mexican, participated in the bidding. All the contracts were awarded.

Interestingly, the three auctions took place over a period of declining oil prices. Their success hinged on whether the contractual terms matched the risk and potential reward of the opportunities on offer. For instance, the first auction’s disappointing results may have been caused by its focus on exploration. The second auction was for fields already in production, and its combination of improved terms and less risky ventures yielded a better outcome.

Outlook

With the increasing success of the bidding rounds, it seems that Mexico’s energy reforms have put the country on the right path toward stopping and reversing its production decline. The EIA estimates that the measures will lead to a stabilization of oil output at 2.9 Mb/d through 2020, after which production will gradually rise to 3.7 Mb/d by 2040. The agency warns, however, that its projections are contingent on the future success of the reforms, resource and technology developments, as well as world oil prices.

The current low price environment could jeopardize the investment private companies are willing to make in the sector. Given the geologies and technologies involved, takes time to develop oil fields.

There is also political risk to consider. The government did not find it easy to pass the reform legislation; opposition was pronounced, with many Mexicans equating the changes to “selling off” a national treasure – Pemex. Concerns have also been expressed about the 2018 presidential election, where polls show the early front-runner is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador – known for his opposition to the oil-industry reform.

It is still early to call Mexico’s energy overhaul a success. Just like any other major reform, it cannot be expected to change a country’s mindset and institutional structure overnight – especially if it makes a clean break with a long-standing and radical tradition.

The article was first published on Geopolitical intelligence Services