Dr Carole Nakhle

Dr Carole Nakhle

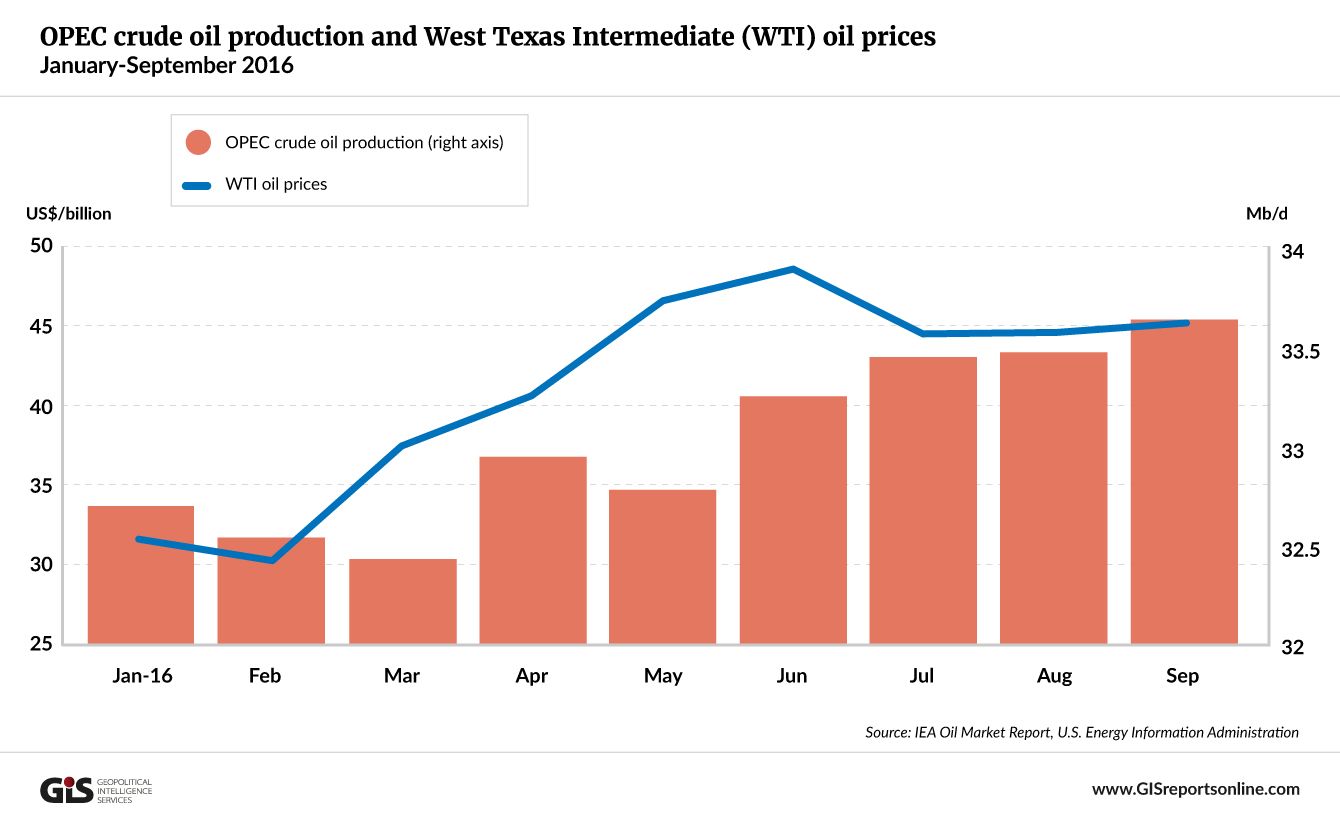

For the first time since 2008, OPEC has announced a coordinated production cut of approximately 0.5 million barrels a day (Mb/d), limiting its total output to 32.5-33 Mb/d. The decision at an informal OPEC meeting in Algiers surprised the international community, because it broke with the organization’s relatively recent practice of not trimming output after crude prices collapsed in the summer of 2014.

Over the past two years, OPEC has focused on regaining market share; the forces of demand and supply were allowed to set prices. A preliminary attempt to change that course was tried in Doha in April 2016, but it failed – primarily due to disagreements between Iran and Saudi buy accutane online acne.org Arabia, which have each raised oil output by more than 1 Mb/d since late 2014.

Saudi Arabia, the organization’s largest producer, clearly stated before the Doha meeting that it would not apply any production freeze or cuts unless all members followed suit. Iran would not abide by this proviso because it wanted first to restore production to its level before Western sanctions were imposed. At Algiers, these differences seem to have been overcome, probably because Iran got some sort of exemption from the production cap.

Big questions

For oil producers, this is surely a positive development because it restores OPEC’s image as an organization that can act cohesively despite the (political) rivalries between its members.

Prior to the Algiers meeting, some commentators declared OPEC was dead. Considering that the organization still supplies more than 40 percent of the world’s oil, such statements are rather premature. However, there are still strong forces at work in the global oil market – both on the demand and supply sides – that are likely to weaken the impact of OPEC’s intervention in the short to medium term.

What is notable in the post-Algiers announcement is the absence of details and specific targets for each country. These were left for the organization’s next meeting in November, when the Algiers agreement is expected to come into force.

It remains to be seen whether the terms of the deal will be implemented and respected, and more importantly, whether the announced production cut will be enough to achieve its aim of putting upward pressure on oil prices.

Record month

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), OPEC crude production reached a record high of 33.5Mb/d in August 2016, with most of its largest producers in the Middle East aiming high.

Saudi Arabia regained the throne it lost to the United States in 2014, becoming the world’s largest oil producer at 10.7 Mb/d. Production from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kuwait climbed to record highs of 3.07 Mb/d and 2.9 Mb/d, respectively.

Iran is edging closer to its pre-sanctions level of 3.8 Mb/d as output has expanded gradually to over 3.6 Mb/d. But Iranian ambitions appear to extend beyond the pre-sanction levels. The country is hoping for a bigger production boost after its next licensing round, which will see a new type of oil contract offered to foreign companies. According to Iran’s authorities, these buyback contracts, called Iran Petroleum Contracts (IPC), will attract significant international interest.

Iraqi production has also continued to expand rapidly, although its momentum is beginning to slow. In 2015, the country posted the world’s biggest annual increase in oil output of 23 percent, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy. In August 2016, Iraq reached 4.4 Mb/d.

Saudi cuts

Against this background, one cannot help but wonder which OPEC member will actually cut output and by how much. An even more important question is whether those reductions will be enough to have any meaningful impact on the market.

On the positive side, Saudi oil production typically slows down in the autumn, as local power demand eases along with the desert heat. This seasonal pattern is linked with the heavy electricity usage in summer months from air conditioning and cooling systems. But even if Saudi Arabia makes its traditional output adjustment to lower domestic demand, it will not be enough to satisfy OPEC’s new production target. It remains to be seen whether the kingdom is willing to assume in full the additional reductions necessary.

The burden of this cut becomes even greater if Iran is allowed to keep expanding its production to the pre-sanctions level. The situation could deteriorate further if Libya and Nigeria – high-capacity exporters that have suffered from significant supply disruptions – manage to resuscitate their production. Meanwhile, a race for market share appears to be taking place inside of OPEC, with Iraq and Iran increasing their slice of the pie at the expense of Saudi Arabia and the GCC countries.

Russian factor

No wonder OPEC is trying to entice Russia, the second largest non-OPEC producer after the U.S., to join forces in taming global production growth.

This is not something new. Several attempts have been made over the years, and all met the same unhappy fate. This history has only deepened the prevailing mistrust between OPEC and Russia. One example is OPEC’s abortive 1999 agreement with some major non-OPEC producers, including Mexico and Russia. In the end, only Mexico delivered on its promises, while Russia enjoyed a free ride.

The truth is, OPEC has found the Russians hard to convince, despite their habit of making the occasional supportive statement and showing solidarity by attending a few OPEC meetings. It is unclear why the current situation should be any different, for all the happy talk by OPEC and Russian officials.

Wild Cards

If one assumes a scenario of successful coordination between OPEC members, compounded by the (unlikely) support of Russia, then oil prices should increase – assuming everything else remains the same.

But even under this optimistic scenario, timing is an issue. On the demand side, the outlook is shaky. The IEA has revised its forecasts downward, stating that “global oil demand growth is slowing at a faster pace than initially predicted.” Meanwhile, OECD inventories are at a record high. Under current market conditions, it will take years for the existing excess of supply in the market to be absorbed, thereby limiting and delaying the effect of any production cuts.

There is also the more important question of how high the oil price can go before it triggers a widespread reopening of North American shale production. Shale oil is perhaps the biggest unknown in today’s global oil market. It is a new phenomenon in the history of this more than century-old industry. Unlike conventional oil, shale is “flexible”: operators can respond much faster to changes in market conditions than is the case with conventional oil, where long lead times between development and production are the norm. Furthermore, shale oil operations have shown impressive improvements in cost efficiency, which means that the previous break-even price of more than $70 per barrel is no longer needed to justify drilling.

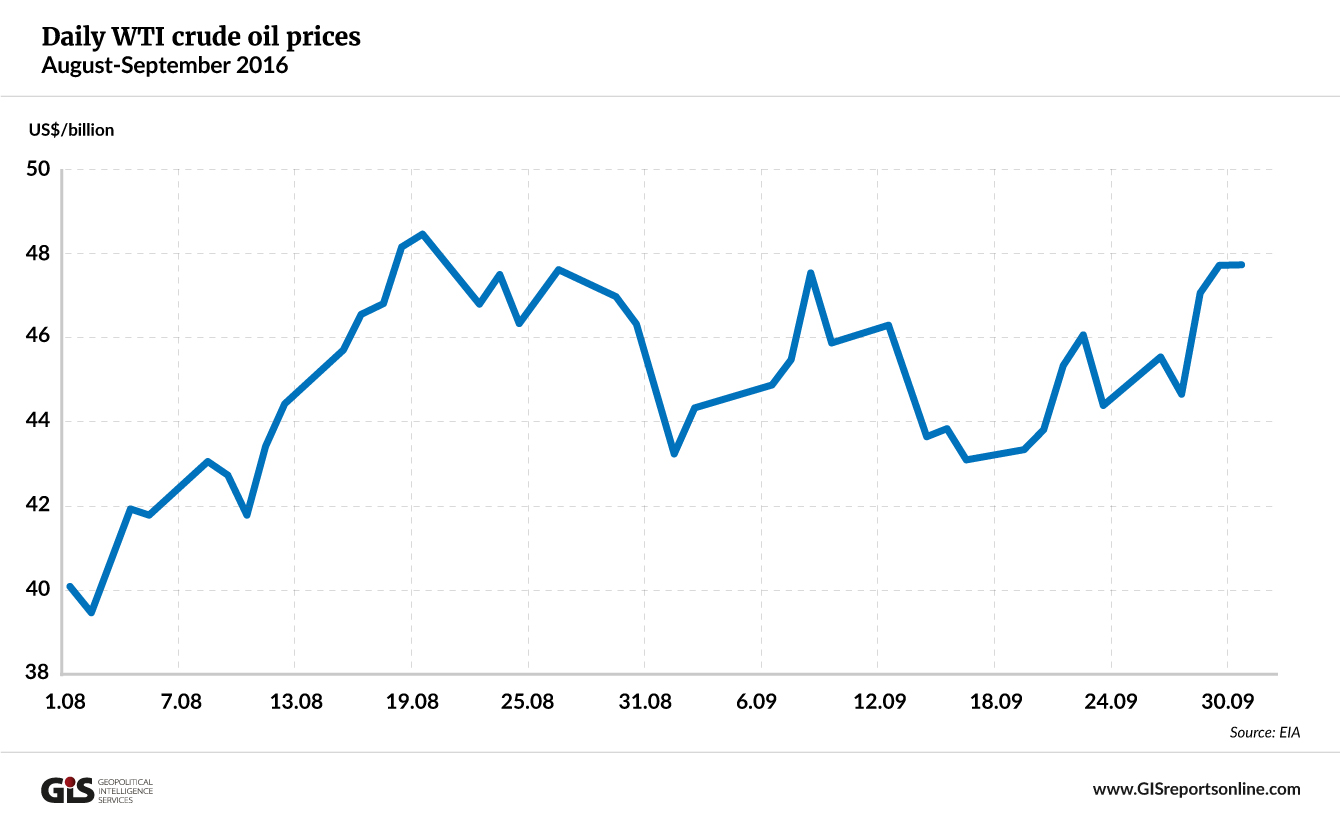

The strengthening in the oil price around the time of the Algiers meeting was expected and short-lived. Today it seems to have reached some kind of ceiling, hovering near $50, a bit more than half the level achieved in 2010-2014. That said, it is worth noting that the oil market is global and volatility is the norm: the track record of forecasting crude prices is remarkably poor.

On balance, OPEC will likely need to brace itself for a rough ride over the next three to four years. The organization’s ability to maintain cohesion during this period will be essential. As the impact of the recent cuts in capital expenditures starts to bite, OPEC may be able to restore its influence over the global oil market. But it won’t be long before the organization (as well as non-OPEC producers) faces another existential threat: climate change. Discussions about oil prices may be less relevant then.

The article was first published on Geopolitical Intelligence Services