Dr Carole Nakhle

Russia’s growing political and military role in the Middle East has captured international attention, especially since the country got involved in the Syrian conflict in 2015. Russia’s activities in the region, however, go much further and increasingly include economic and financial ties, a trend that has been on the rise since 2014.

That year was a tough one for Russia. Its annexation of Crimea in February 2014 prompted Western governments, led by the United States and the European Union, to impose sanctions. These have restricted Russian access to international capital markets, making project financing more difficult.

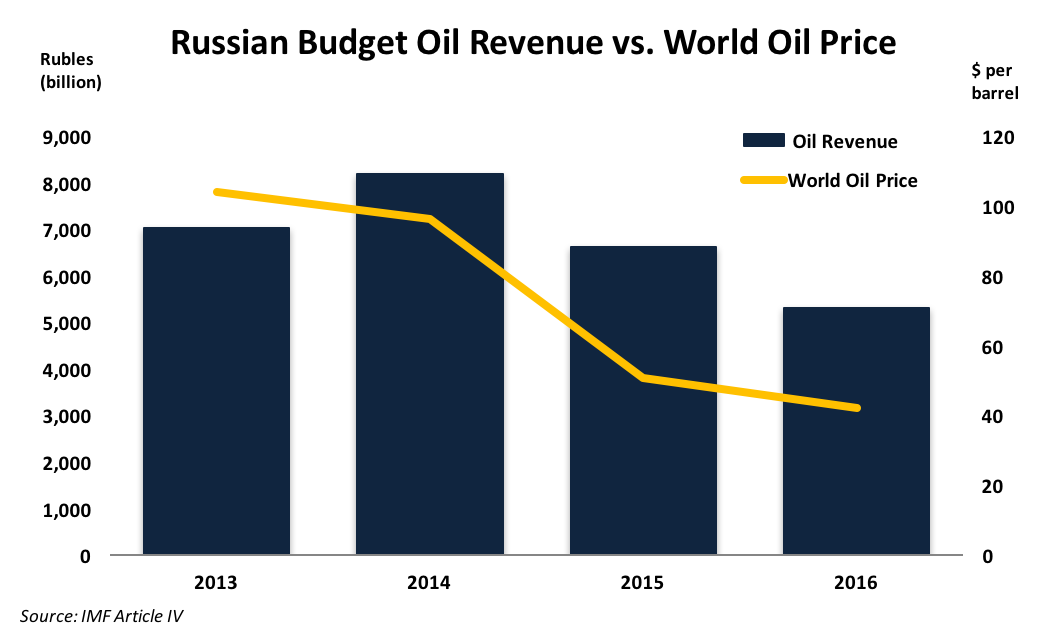

Then, in the summer of 2014, oil prices more than halved, collapsing from a high of around $110 per barrel in June and ending the year at less than $60 – a threshold they still have not yet managed to regain. For an economy where oil and natural gas account for about half of the federal budget revenue, the collapse in prices hit hard.

There is no doubt that the sanctions and the drop in oil prices have put pressure on Russia’s economy. But one would have expected this double whammy to inflict serious enough damage for the Kremlin to soften its stance on Syria and Ukraine. So far, neither has happened. On the contrary, although vulnerabilities remain, the Russian economy’s resilience has surprised many.

Russian efforts

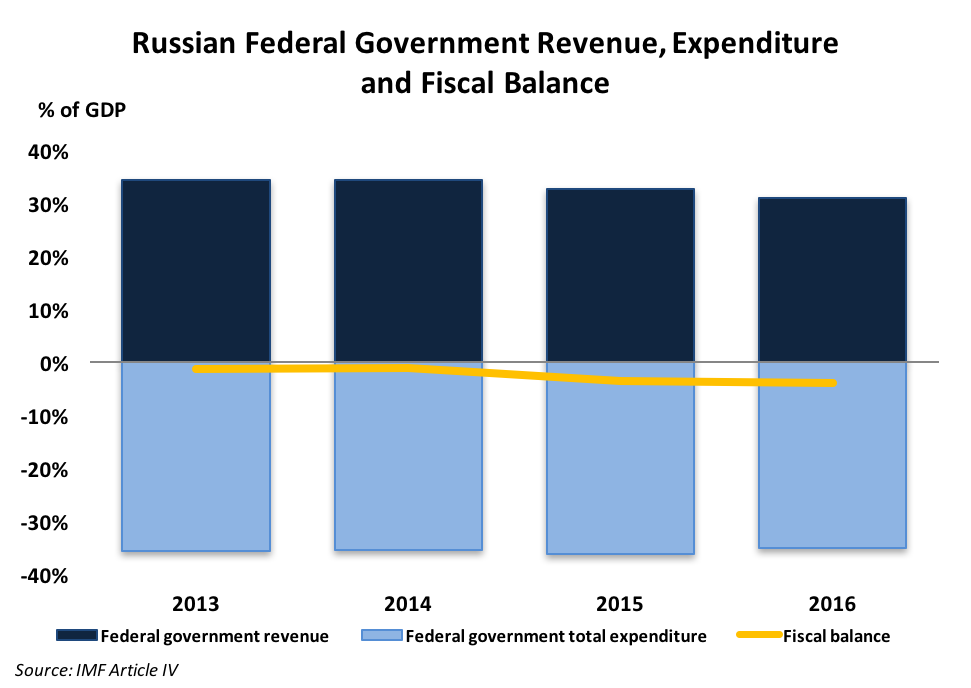

The Russian government quickly took several steps to cushion the economic impact. It implemented structural reforms that have received praise from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In its 2016 report, the IMF pointed out that Russia’s “economic contraction is nonetheless shallower than previous recessions as a stronger external position and the authorities’ economic package – a flexible exchange rate regime, banking sector capital and liquidity injections, limited fiscal stimulus, and regulatory forbearance – cushioned the shocks, helped restore confidence and stabilized the financial system”.

The tighter fiscal and monetary policies have contributed to a decrease in inflation from almost 16 percent in 2015 to about 7 percent in 2016. Russian unemployment is at 5.6 percent, near minimum levels, according to the World Bank.

Having a flexible exchange rate also helped ease Russia’s economic downturn. Unlike many Middle Eastern oil producers, Russia’s currency, the ruble, is not tied to the dollar (it was unpegged in November 2014). This has softened the effects of the collapse in oil prices. Though it receives fewer dollars for each barrel of oil, those dollars can now be exchanged for more (weaker) rubles, which it can use on domestic expenditures. Producers with fixed dollar exchange rates, like Saudi Arabia, have no such luxury.

Another feature that distinguishes Russia from other major oil producers is the size of its economy – the sixth largest in the world. This has made it easier for the government to implement an import substitution policy that has particularly benefited the country’s agriculture sector. In August 2014, it imposed retaliatory sanctions on the West, banning EU food imports until the end of 2017 and boosting domestic production.

A little help from its friends

Aside from using the savings that had built up in Russia’s sovereign wealth fund (SWF), the now nearly depleted Reserve Fund, the government generated crucial funding from privatizations. The most notable of these was the 2016 sale of a 19.5 percent stake in Russia’s largest oil company, Rosneft, to the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the commodities trader Glencore. The price tag was $11.3 billion, the largest foreign direct investment in Russia since the imposition of Western sanctions. The QIA is planning to spend a further $2 billion in Russia. Other major investments from the Middle East have been announced since the sanctions were imposed.

Since its inception in 2011, the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) has received more than $25 billion from global investors, 90 percent of whom are from Asia and the Middle East. In an interview with weekly magazine Arabian Business, RDIF CEO Kirill Dmitriev called the partnership with Middle Eastern investors “a match made in heaven”.

The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), which in 2012 became the first Gulf-based SWF to co-invest with the RDIF, doubled its investment to $1 billion in 2015. The United Arab Emirates’ investment company, Mubadala, launched a $2 billion co-investment fund with the RDIF to pursue opportunities in Russia, while the Abu Dhabi Department of Finance committed $5 billion managed by Mubadala to invest in Russian infrastructure projects. Another partnership with Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) was also announced in 2015, whereby the PIF agreed to invest $10 billion in Russia. In 2016, Bahrain’s SWF, Mumtalakat, announced it would invest $250 million in Russia’s fund for direct investments.

Previously, Middle Eastern SWFs had been more oriented toward investments in the U.S. However, a combination of Western suspicions about the motives behind such investments and a growing perception that the Obama administration was turning its back on the region encouraged the Gulf countries to revise their investment strategies.

Oil rapprochement

The deals will draw Middle Eastern oil producers and Russia closer. OPEC Secretary-General Mohammad Barkindo was reported as saying that the Qatar-Rosneft deal would strengthen the relationship between OPEC and non-member oil producers, describing the deal as “very strategic for all the parties involved”.

In November 2016, OPEC confirmed its first production cut since 2008. What made the deal more striking was that OPEC convinced the largest non-member producers to join in. Altogether, they agreed to cut output by 600,000 barrels per day, with Russia accounting for half of the reduction. Russia’s stance came as a surprise, because it had previously been an unreliable partner for OPEC, making promises to cut but never delivering. Prior to the November deal, Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin downplayed OPEC’s power to influence the oil market and had consistently opposed potential cooperation.

In the end, the Kremlin’s voice was more powerful. News agency Reuters reported that Russian President Vladimir Putin “played a crucial role” in bringing about the agreement, “helping OPEC rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia set aside differences”. Russia benefited from stopping the oil price’s free fall; that it was producing at a record high since the collapse of the Soviet Union made it easier to join the cuts.

Two-way street

With more than 80 projects carried out in the Middle East between 2003 and 2016, Russia’s footprint in the region is becoming more visible. In the energy sector, Russian companies are active in petroleum exploration, production and trading. Russian oil and gas companies Lukoil and Gazprom Neft Middle East B.V. are involved in projects in Iraq. In 2016, Russia and Iran signed a strategic five-year plan that included 13 agreements focusing on energy, construction and trade. Rosneft is offering advance payment for future crude oil deliveries from Iraq’s Kurdish Region.

Russian firms are also playing a big role in the development of nuclear power in the Middle East. Russia built Iran’s first nuclear power plant, in Bushehr, and in 2014 agreed to build eight more nuclear reactors in the country. Rosatom, the state-owned nuclear corporation, will build Jordan’s first nuclear power plant, which is projected to become operational in 2023. Russia and Saudi Arabia signed an agreement to cooperate on nuclear energy development in 2015.

Game of chess

Russia is not after the Middle East’s natural resources. After all, it is a vast, resource-rich country. It also sits on the world’s second-largest proven gas reserves (after Iran) and sixth-largest oil reserves (after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Iran and Iraq). It has the world’s largest shale oil deposits and ninth-biggest shale gas deposits (after China, Argentina, Algeria, the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Australia and South Africa). Furthermore, Russia produces its oil and gas at low cost.

Energy deals, particularly in the nuclear sector, are known for their long-term nature. They can therefore support wider economic and political cooperation initiatives spanning decades to match such projects’ long life cycles. It is likely that more deals will be announced between Russia and countries in the region, especially considering Moscow’s growing political role there.

However, such deals will not be without controversy, primarily because of the tense political rivalries between Middle Eastern countries – Iran and Saudi Arabia, for instance – and within them, such as the Kurdish Region and the Iraqi government in Baghdad. Navigating such complex geopolitical realities will require some very smart maneuvering.

The article was originally published on Geopolitical Intelligence Services