Dr Carole Nakhle

TUNISIA initiated the Arab Spring wave which toppled decades of dictatorship in several countries. Its success in charting a course for itself after President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled the country in January 2011 will allow its people to move into a new era of fairer political representation, sustainable economic development and wider social inclusion. It will also be a model to aspire to for all those who are desperate to see that their revolution was worth it. The road, however, will not be smooth.

Small but powerful

TUNISIA is a small yet powerful country: it opened a new chapter in the history of the Arab world. The country initiated the wave of the Arab Spring which saw several dictators toppled – from President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia in January 2011, to the fall of Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011 in Egypt and the ousting of Libya’s President Muammar Gaddafi in October 2011. The ability of Tunisia to transition from 23 years of control under President Ben Ali to a well-functioning society and robust economy post-Ben Ali has been watched closely by many across the world. Success will prove that the revolution was worth it.

Tunisia, however, remains in the grip of political instability and its economic recovery remains frail. It would have been simplistic to expect a rosier outcome. As acting Prime Minister Mehdi Jomaa said, the Tunisian economy needs at least three more years of painful reforms to revive its growth.

Many experts believe this is optimistic. It will require a strong government to maintain the coherence of the country during such a challenging, lengthy period. The Tunisians are proud that they started the ‘Arab Spring’ but some are increasingly nostalgic for ‘the good old days’, as they suffer the burden of transition.

The revolution

Before the revolution, Tunisia was seen as the most stable Arab country. Some analysts argued it could become a ‘North African Singapore’. The country’s GDP was nearly twice that of Morocco, and Tunisia came 40th in the world on Global Competitiveness Index 2009–2010 rankings and the most competitive economy in Africa.

Today, the Tunisian economy is registering modest growth. GDP was 2.8 per cent in 2013 compared with 3.6 per cent in 2010, as the agricultural and the oil and gas sectors have declined while manufacturing stagnated. Tunisia was pushed down on the global competitiveness scale, scoring 87 in 2013. Tunisia’s 15.3 per cent unemployment rate, while declining, remains above the pre-revolution level of 13 per cent.

However, to conclude that the Tunisians were better off during Ben Ali’s dictatorship is simplistic. Before the revolution, Tunisia sat near the bottom of social freedom lists.

When President Ben Ali allowed the nation’s first multiparty elections in 1999, he claimed more than 99 per cent of the presidential vote, while maintaining monopoly over business despite some economic reforms.

Notwithstanding an overall positive assessment in its 2010 report, the World Bank warned about the Tunisian economy’s inability to generate sufficient jobs to employ the growing labour force, with young and educated individuals increasingly hit.

European trading partners

The economic slowdown is not only linked to domestic conditions. A study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2010 concluded that Tunisia’s annual growth rate was increasingly synchronised with the growth rate of its main European trading partners.

Tunisia’s economy is highly dependent on the European Union (EU) for exports, tourism receipts, remittances, and Foreign Direct Investment inflows.

Europe accounts for around 75 per cent of Tunisia’s total exports and around 85 per cent of total remittances and tourism receipts.

When the economic recession hit the EU in 2008, the Tunisian economy suffered after experiencing growth rates of more than six per cent in 2007. The country has also suffered from the unrest in Libya, which is a substantial market for, and employer of, Tunisians.

Supported by the international community, the Tunisian government has embarked on a number of policy reforms, including reducing energy subsidies and improving the investment climate, in an attempt to support faster economic recovery.

The implementation of these measures continues to be hampered by political volatility.

Wasteful consumption

Energy subsidies weigh heavily on the government budget. Their cost tripled from an average of 0.9 per cent of GDP before 2010 to 2.8 per cent in 2012, mostly benefiting the richest population. According to the IMF, the highest income households in Tunisia benefit almost 40 times more from energy subsidies than those on the lowest income.

The government increased fuel and electricity prices by around eight per cent over the last two years, with a view to gradually phasing out subsidies.

The reduction in energy subsidies not only eases the fiscal burden but also helps to reduce wasteful consumption and improves energy accutane purchase uk efficiency – the latter being another essential target of the new energy agenda.

In 2013, the government launched the National Energy Dialogue, where open, public debates have been organised across the country to discuss the future of energy in Tunisia by 2030. This is a positive step.

Production decline

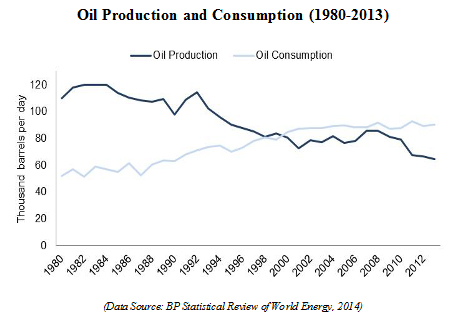

The Tunisians are concerned about the shift in the energy balance, since 2000, going from a surplus to a deficit and which is likely to continue as domestic consumption maintains its growth while production declines, thereby increasing the country’s dependence on imports.

The government wants to establish a more diversified energy mix especially by enhancing the contribution of renewable energy. The dominance of oil in the primary energy mix has been eroded, from 71 per cent in 1990 to 45 per cent in 2011. Natural gas has gradually crowded out oil to become the new dominant fuel; its share in the primary energy mix increased from 28 per cent to 55 per cent over the same period.

In 2013, 98 per cent of Tunisia’s electricity generation came from fossil-fuelled power stations, with hydroelectric and wind sources supplying only two per cent of total generation.

The government aims to raise the share of renewable energy to 30 per cent of electricity by 2030.

Another important target the government is focussing on is the development of national hydrocarbon resources, both conventional and unconventional, with the help of international oil and gas companies.

Corporate landscape

It is true that Tunisia is a relatively small oil and gas producer and unlike many Arab countries, its economy is diversified; its reliance on oil is limited as sectors such as agriculture, tourism and manufacturing, play equally, if not more, important roles. But, in the oil and gas sector, Tunisia has a diverse corporate landscape, with 60 companies actively operating in exploration.

Before the revolution, Tunisia was seen as an attractive area for oil and gas investment despite its limited potential. Between 2008 and 2010, Tunisia awarded the most exploration blocks in North Africa. Post revolution, investment has suffered from political instability, delays in getting oil and gas development plans approved, and demands for greater public say. Still, for British multinational oil and gas company BG Group – Tunisia’s largest gas producer – for instance, the country is a more reliable place than Egypt with respect to paying its bills on time.

Oil production has been steadily declining from its peak of 120,000 barrels per day (bl/d) in the mid-1980s to 60,000bl/d in 2013.

Gas production reached 66 billion cubic feet (bcf) in 2012, satisfying around 50 per cent of domestic demand; the rest is imported from Algeria.

Tunisia hopes to reverse its production declines and attract new investment by encouraging exploration of unconventional resources, which dwarf its conventional potential. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), Tunisia’s proved oil reserves are approximately 425 Million Barrels (Mbls), compared with 1,500 Mbls of technically recoverable shale oil resources. Similarly, proved gas reserves are only two trillion cubic feet (tcf) compared with 23 tcf of shale gas resources.

Since Shell expressed interest in exploring Tunisia’s shale resources, opposition has been fierce. The main concerns are over water scarcity and environmental impact, in addition to the absence of tailored legislation and regulations which take into consideration the specific features of shale oil and gas.

Despite existing criticism, the government announced it was considering the offers of different companies which want to drill for shale gas. The Anglo–Dutch multinational Shell is committed to drilling four wells if the new government approves the three-years pending licence.

Shale potential

The evaluation of Tunisia’s shale oil and gas potential is at a very early stage. There is no doubt that if the country’s shale potential is proven, the economic contribution will be significant. However, it is premature to engage in such forecasts. The success or failure of shale development in Tunisia, like in any other country, will depend on a combination of factors: the fiscal terms, planning procedures, environmental regulations, water management processes, local support, service sector availability and proven geology.

Open dialogue between potential investors and concerned communities, in addition to building local capacity, are therefore essential steps for investors to obtain the social licence to drill. An improvement in the oil and gas investment climate will have a positive spill-over in other sectors of the economy. The government has shown commitment to pursuing its economic and social reform agenda. As expected, it will continue to face many obstacles. But the commitment to transparency will remain an important remedy to lowering, and even removing, those obstacles.

The Tunisians have already expressed their tiredness of corruption, opacity and monopoly in the management of the country.

Article Reproduced with the kind permission of Geopolitical Intelligence Services