Dr Carole Nakhle

Since 2009, international interest in the Eastern Mediterranean’s offshore oil and gas resources has followed a cycle from widespread excitement, to a stall in activity, to disappointment and back to excitement again. The Levant Basin has seen several discoveries that could have a big impact on domestic economies. However, unless circumstances locally, regionally and globally align favorably, the area will not fulfill its potential as a gas exporter.

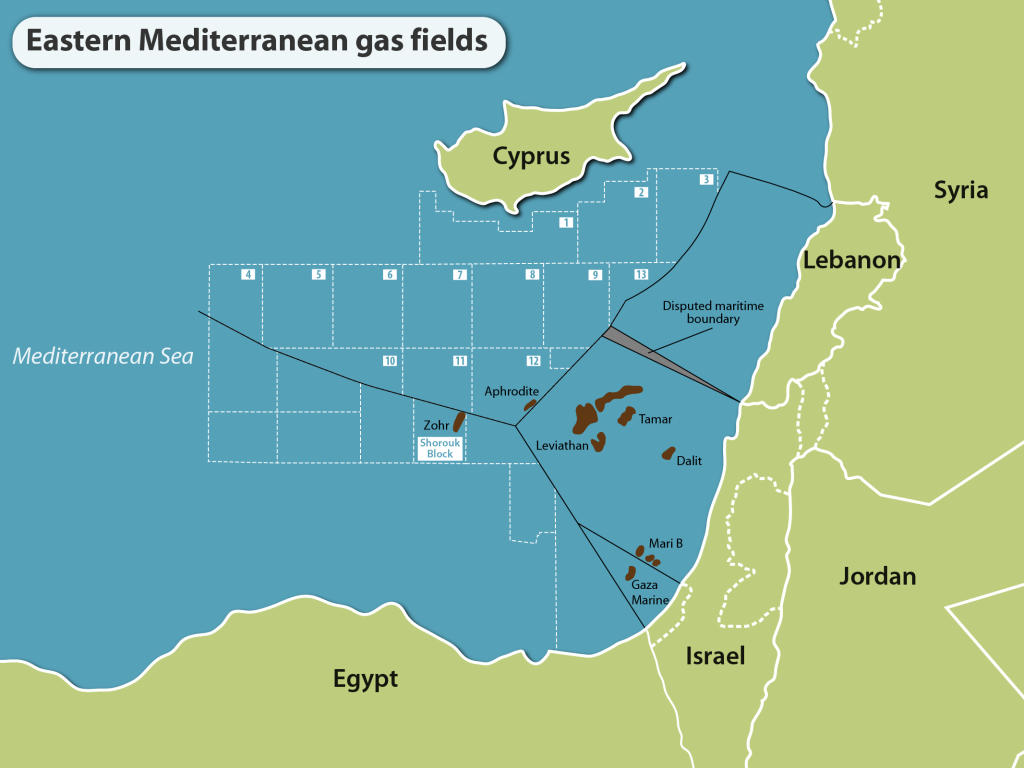

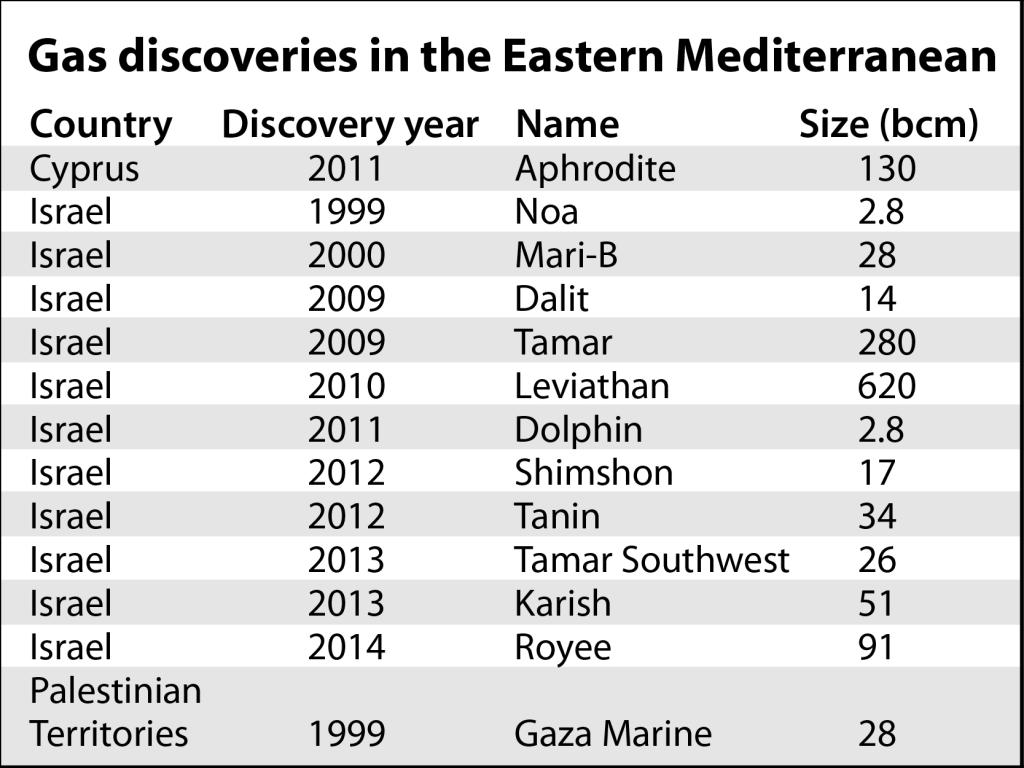

The best known discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean are Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan fields, discovered in 2009 and 2010, respectively. These were hailed as the two biggest gas discoveries of the last decade. Excitement in the region’s potential was stoked by the March 2010 publication of a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) report on the Levant Basin, which said there were 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and 3,500 billion cubic meters (bcm) of recoverable gas possibly lying under the seabed (see map).

So far, only the basin’s gas potential has been proven, mostly in Israeli waters. British Gas (BG) announced the discovery of Gaza Marine in the waters of the Palestinian Authority in 1999. Cyprus made its first, and to date only, discovery – the Aphrodite field – in 2011. Lebanon is yet to initiate a licensing round that would give the green light to exploration. Syria was a small oil and gas producer before its civil war erupted in 2011, when exploration was put on hold.

Transformative potential

Following the discoveries, analysts repeatedly described gas from the Eastern Mediterranean as having the potential to transform the region and global energy markets. It was thought the resources could reshape local domestic economies, frame regional geopolitics and provide an alternative source of gas to Asia and Europe, reducing the latter’s dependence on Russia.

It is true that local economies stand to reap big economic benefits when the gas is exploited effectively and sustainably. A notable feature among most of the region’s countries is the absence of natural gas from the energy mix. Cyprus and Lebanon generate their electricity almost entirely from oil products, resulting in hefty import bills, especially when oil prices are high. Until 2004, coal imports dominated Israel’s power sector. However, natural gas has increasingly gained market share following the start of production in the Mari B field. The Palestinian authorities depend heavily on Israel for meeting their energy needs.

Any domestic production should therefore improve these countries’ finances, while bringing in foreign capital and promoting job creation throughout the supply chain. For natural gas in particular, building the infrastructure will prove a major undertaking.

Exploitation and export

Israel is far ahead of Cyprus and Lebanon in exploiting offshore gas resources. Several Israeli fields already produce gas for the domestic market.

For Cyprus, the Aphrodite field has been a mixed blessing. A 2013 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that even if Cyprus gasifies its entire economy and no new discoveries are made, there would probably still be enough gas left to consider exporting from the field.

However, exporting is fraught with technical difficulties. Compared to offshore pipelines, the more sensible option would be liquefied natural gas (LNG). Yet in order to commercially justify the building of an LNG plant, the minimum field size would need to be in excess of 170 bcm. The size of the Aphrodite field was estimated to be 142 bcm. This means that Cyprus would need to make new discoveries and/or obtain additional supplies from its neighbors for re-export. However, aside from the Aphrodite discovery, exploration has so far been unsuccessful. Groups that have carried out exploration activity include a consortium of Italian energy firm Eni and South Korea’s Kogas (which holds Blocks 2, 3 and 9), and France’s Total (Blocks 10 and 11).

Regional cooperation

Cyprus hopes to become a regional gas hub, but the animosity among its neighbors, including Lebanon and Israel, which are still officially at war, has been a challenging hurdle to overcome.

Earlier this year, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to strengthen energy cooperation between their countries. What that will mean in practice remains unclear. A pipeline from Cyprus to Greece would be expensive and technically challenging because of the structure of the seabed between the two countries. Geopolitical tensions between Cyprus and Turkey make a pipeline between those two countries unlikely. Exporting Israeli gas to Cyprus for re-export has been mooted on several occasions, but little material progress has been made so far.

Lebanon has been stuck in a political stalemate, with no president since May 2014. Two essential decrees – the contract terms and block delineation – have been pending government approval since 2013. Without these, the country’s first licensing round, which has already been postponed several times, cannot go ahead. Seismic surveys carried out in Lebanese waters have indicated significant potential. However, until companies are able to start exploration activities, one cannot know for sure if the resources are there.

As for Gaza Marine, the future of the field’s development remains highly uncertain, especially in the light of the continuing buy accutane online in canada conflict between Israel and Hamas. As put by the Brookings Institution, a think tank, the development of the field primarily depends on Palestinian-Israeli cooperation.

Regulatory risks

Even in Israel, investors have faced difficulties. Energy security is, understandably, a sensitive topic in a country that sees itself as a politically isolated island in the region. Many Israelis are uneasy about the country exporting its natural wealth.

The political and business risks in Israel are high. Between 2000 and 2013, the country’s regulatory and fiscal framework for upstream oil and gas was revised on several occasions, denting investor confidence. In 2012, the government announced that it would cap gas exports at just 40 percent of potential reserves in order to guarantee domestic supply for the next 25 years. There have also been calls to impose additional taxes on future gas exports.

More recently, the development of Israel’s largest gas fields was put on hold after the antitrust authority voiced concerns over a lack of competition and called the consortium of Noble Energy and Delek, which controls the Tamar and Leviathan fields, a monopoly. Although last year a deal was reached that required the partners to sell off some smaller assets, further interruptions could still occur.

Prices and competition

The decline in oil and gas prices has amplified the difficulties in the region and brought into question whether developing the fields is commercially viable. The fall in the oil price by more than 70 percent since the summer of 2014 has led to project cancellations and delays.

Gas prices have also declined substantially. Combined with increasing competition from new LNG supplies coming from Australia and the United States, a substantial increase in gas prices – as witnessed in 2013 – may not occur for some time. Accordingly, Cyprus has indicated that it may alter its LNG plans. In February 2015, the island signed a memorandum of understanding to deliver gas from the Aphrodite field through an offshore pipeline to Egypt for re-export. Aphrodite is due to start production in 2020.

Competition has also come from within the region. Eni’s 2015 discovery of 850 bcm of gas in the Zohr field offshore Egypt has not only altered that country’s market, but has forced its neighbors to revisit their own plans. Both Cyprus and Israel had originally hoped to export some of their gas to Egypt. However, since Zohr is set to start production as early as 2019, their supplies will not be needed.

Fired up

On the positive side, the discovery of the Zohr field has reignited excitement in the region. Since the field is located in Egypt’s Shorouk Block, adjacent to Cyprus’s Block 11 where Total carried out its initial exploration, and near Block 12 where Noble Energy found the Aphrodite field, its discovery will boost exploration activity nearby. The Cypriot government and the Eni-Kogas consortium recently agreed on a two-year extension of the initial exploration phase for the consortium’s blocks. Total, which previously was rumored to be considering giving up its rights, now plans to do more exploration.

Officials in Lebanon have started to push hard for the two pending decrees to be finalized. They fear that the country is being put at a disadvantage by further delays while its neighbors are rushing to secure their future markets.

Wider impact

It is unlikely that Eastern Mediterranean gas will transform world gas markets in the near future. The discoveries made so far are not large enough to make such a big difference, while exports may only begin well after 2020.

Given the limited export options, many experts hope that the development of Eastern Mediterranean gas resources can encourage countries in the region to cooperate, starting with a cautious rapprochement between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Reconciliation between Lebanon and Israel is not expected in the foreseeable future. However, it cannot be completely dismissed – economic interests may prove more powerful than politics. If relationships between bigger powers, such as Iran and the U.S., are normalized, this could help provide impetus. The result would be a new gas export market that will bring significant change to local economies and regional politics.

- In 1999, Israel made its first offshore natural gas discovery – the Noa field

- The Tamar discovery was the largest conventional gas discovery in the world in 2009, while Leviathan was the largest deepwater natural gas discovery in the world over the past decade

- Israel has agreed to supply gas to Jordan and Palestine

- If Cyprus fully gasifies its economy and no new discoveries are made, the reserves in the Aphrodite field would last 16 years. If Cyprus gasifies its power sector alone and does not export, the gas would last nearly a century (MIT, 2013)

- Around 52 international oil companies submitted the pre-qualification applications for Lebanon’s first licensing round and 46 were short-listed, in 2013

- The Zohr field is the eighth largest gas discovery since 2005

Article reproduced with the kind permission of Geopolitical Intelligence Services

The article was first published on 1 March 2016