Dr Carole Nakhle

AlI around the world, one cannot but notice the remarkable effort towards achieving greater gender equality and empowering women across various industries. The energy sector is no exception. The list of benefits from such a noble cause is extensive, whether for the economy and society or individual organisations and companies.

A closer look, however, reveals that, despite the enthusiasm, a lot remains to be done. When it comes to women’s participation, the oil and gas industry, in particular, is starting from a very low base, even though it is more than a century old. That base further dwindles in higher echelons.

In an era where the global fight against climate change is strengthening countries’ determination to transition to the post oil and gas age, the industry can ill afford to be influenced by gender considerations. Supporting and promoting women’s contribution in all ranks can bring vital new perspectives and reinvigorate the industry’s image that may well have been lacking in ‘traditional oil’, to the industry’s great cost.

Many gender equality initiatives mushroomed following the United Nations’ (UN) declaration of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, then their successors, the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. In both agendas, gender equality is set as a standalone objective for all nations to realise, with women’s empowerment portrayed as a core condition to achieving sustainable development.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – Source: UN, 2015

Sustainability

Gender equality is more than just a question of morality and fairness. The UN states that “gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world”.

“For the global economy to reach its potential, we need to create conditions in which all women can reach their potential”, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Economic Counsellor and Director of Research, recently argued. In its 2017 annual report, the IMF shows that countries of all income levels would see significant increases in their gross domestic product if women’s labour force participation were increased to match men’s. Additional benefits include: achieving greater economic diversification, and more equal income distributions. Similarly, in its World Development Report (2012), the World Bank maintains that eliminating barriers discriminating against women in certain sectors and occupations could increase labour productivity by 25%.

At a company level, the case for supporting women’s participation is equally compelling. A global survey of 21,980 firms from 91 countries carried out by the Peterson Institute shows that a move from no female leaders to 30% representation is associated with a 15% increase in the firm’s net revenue margin.

In its report ‘Investing in Women’s Employment: Good for Business, Good for Development’, the International Finance Corporation identifies several benefits for companies which are investing in good working conditions for women, including enhancing productivity and improving the company’s relationship with local communities.

Despite the evidence and the good intentions, the road ahead is steep. The gender gap, which measures the difference between women’s and men’s labour force participation rates, best illustrates the situation. At a global level, the gap decreased between 1995 and 2015, but the change was quite small (less than 5%), according to the International Labour Office. The largest gender gap was recorded in the Arab region at 55%, followed by Southern Asia and Northern Africa each at 51%.

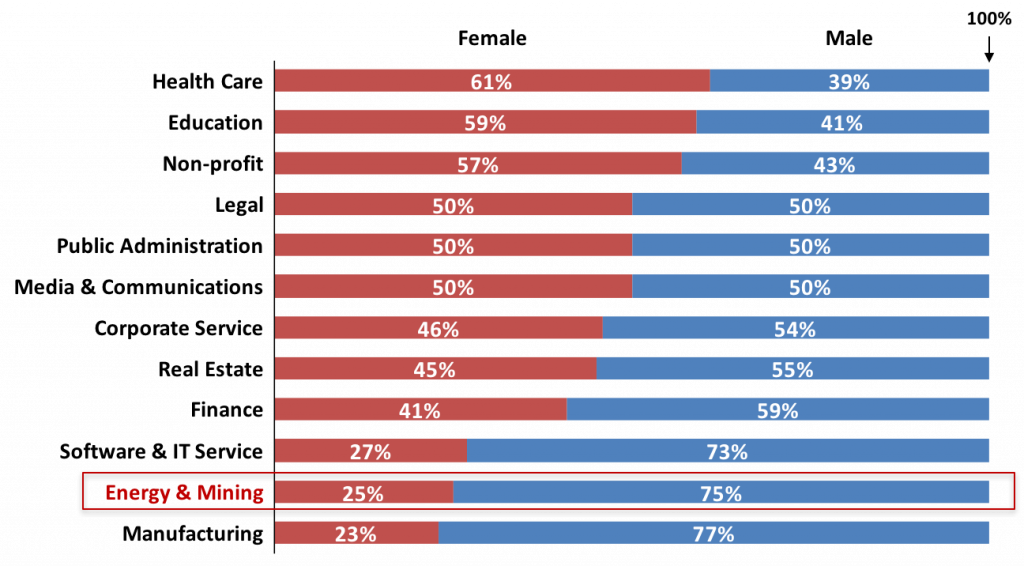

In the energy sector, the disparities between men and women are more alarming. The sector has one of the lowest women participation rates with 25% (including mining) according to the World Economic Forum. The figure further worsens with rising seniority. The Boston Consulting Group found that the share of female employees in the oil and gas industry is around 25% at entry and mid-career levels, dropping to a deficient 17% at senior and executive ranks.

Although the international oil companies have double the female participation compared to national oil companies, the number of such companies from both quarters which ever had a female CEO is remarkably low, so is the number of female energy or oil ministers. In the entire oil and gas rich Arab region, for instance, Tunisia is an exception, with its female Industry, Energy and Mining Minister appointed in 2016.

Employment Share by Gender in Selected Industries – Source: World Economic Forum, 2017

Even industry events remain dominated by men, with one session after another ignoring the startling modern reality of balanced representation. Gatherings that fall on the other extreme typically focus on women’s experiences and related issues, unintentionally risking the danger of weakening their drive for showcasing female capabilities and expertise in the sector.

No Excuse

Several reasons have been given for such a disappointing performance, but one can hardly find a single convincing answer. Traditionally, the industry was seen as a male preserve of tough well-head operatives and oil spattered engineers struggling with giant spigots – not a profession that was physically appealing or that women could discuss openly and proudly in social circles. Such an image is so outdated; the advance in technology, and the use of sophisticated computer models have brought huge simplifications, radically reducing the need for physical effort. Muscle has simply become less important than analytical ability. Gender matters not at all.

Then there is the argument that the industry did not grow fast enough in the 1970s to open up and change, especially the composition of students, towards more women, as happened in the medical field. It takes time to attract petroleum engineers and geologists to change the face of an entire industry. The plain fact today is that too many graduates regard oil and gas as yesterday’s energy sectors and want to concentrate instead on trendy areas such as wind power or solar power. The oil and gas industry is going to need all the talent it can find.

The long-term outlook of the industry is looking increasingly austere. The whole energy scene is changing, and serious challenges are constantly emerging; the growing concern about peak oil demand is one prominent example. While technology and innovation can help, the longevity of the industry will depend on the supply of well-educated and experienced employees, both male and female. Any great industry, such as energy, or any society or economy trying to advance while favouring only half the workforce over the other is bound to stagnate and retreat.

The article was first published by Oil and Gas Middle East