Dr Carole Nakhle

Back in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Caspian Sea was described as the next Alaska or North Sea for the oil and gas industry. But it could never be that, for the simple and obvious reason that the Caspian is landlocked. Moreover, its five littoral states – Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan – have yet to resolve their long-standing territorial disputes, which have prevented full exploitation of the Caspian Sea’s energy potential.

The end of this stalemate may well be within reach, as the region’s leaders have recently advocated a resolution by the end of this year. While this is surely good news, local producers will have to adapt to new realities – especially in the oil and gas markets, which look very different from 30 years ago.

Sea of peace and friendship

The Caspian Sea lies at the heart of the truly central region in the world, connecting Central Asia to Europe and Russia to the Middle East. It has often been described by the heads of the littoral states as the “sea of peace and friendship.” Its long-disputed legal status, however, tells a different story.

Prior to 1991, only two nations bordered the Caspian Sea: the USSR and Iran. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the number of littoral countries increased to five, leading to complex and intractable disputes over territorial claims and legal status. Although the Caspian is called a sea, some bordering states have argued that it should be legally defined as a lake. Each classification has different implications for the delimitation of the borders and ownership of offshore resources.

If the Caspian is a sea, then the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (UNCLOS) would apply and the seabed would be divided according to each country’s coastline. If it is defined as a lake, however (making it the largest lake on Earth), then its floor would be divided evenly between the bordering states. Not surprisingly, the country with the shortest coastline, Iran, has opposed the sea definition and has called for an equal division (20 percent each) of the body of water.

Until a single definition is agreed upon, the Caspian’s legal status will remain unresolved and its offshore hydrocarbons potential will not be fully exploited. For instance, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan have overlapping claims on the Serdar (Turkmenistan)/Kyapaz (Azerbaijan) field, which is located on the median line between the two countries and still awaits development.

The legal dispute has also hindered the buildup of oil and gas export infrastructure. If the Caspian is defined as a lake, then all countries would have to agree before a pipeline is constructed across it. The Trans-Caspian pipeline that would run from Turkmenbashi to Baku before connecting to the European gas market – a crucial element of the European Union’s Southern Gas Corridor – was first suggested more than two decades ago, but opposition from Iran and Russia has stalled its construction.

Recently, however, there have been hopeful signals, particularly from Kazakhstan and Russia, that the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea is almost ready to be signed by the five states. Should this prospect materialize, the region has a better chance to tap its oil and gas resources.

A little history

The history of oil in the Caspian Sea is much older than its bordering countries as we know them today. The first offshore oil well is believed to have been drilled back in the 19th century, when Caspian oil production accounted for around half the world’s oil supply, with the other half mainly coming from the United States.

Today, the region contains some of the world’s largest oil and gas fields. The Kashagan oil field, discovered in 2000 in Kazakhstan, was then hailed as the largest oil discovery in 50 years; it is currently the largest offshore oil field outside the Middle East. The Shah Deniz gas field in Azerbaijan is the largest gas field in the Caspian Sea and among the 20 biggest in the world. Another key installation is the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, an important export route that transports Caspian oil and gas – mainly from Azerbaijan – to European and global markets.

After 1991, the U.S. had hopes that the Caspian Sea could become an alternative to the Middle East as a source of oil, especially because its states, apart from Iran, do not belong to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Around that time, the high level of American enthusiasm was shown by a bumper sticker popular with U.S. diplomats in Central Asia, which read: “Happiness is multiple pipelines.” The EU also hoped that supplies from the region would reduce its dependence on Russian gas. There were also the Indians, Japanese, Turks and of course the Chinese – all energy-hungry and looking for new oil and gas suppliers.

However, a cruel reality gradually sank in: the availability of oil and gas resources in the ground is no indicator of future production performance. Several factors can hinder the transformation of proven deposits into usable product.

Counting potential

Before elaborating on those factors, it is worth putting the potential of Caspian oil and gas into perspective. All estimates of resources have an inherent level of uncertainty. In the Caspian, this is particularly true because the region’s geology has yet to be fully explored. Initial estimates for the Caspian turned out to be particularly over-optimistic, leading to hyperbolic claims that the region would become the next Middle East.

In 2003, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated the Caspian basin area to hold 48 billion barrels (bn bls) of oil and 292 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas in proved and probable reserves. Because these figures conflate proven and probable reserves (proven reserves have a better than 90 percent chance of being produced, while probable reserves have a better than 50 percent chance), they are closer to a high-end estimate.

By comparison, the Middle East’s proven reserves alone amount to more than 803 bn bls of oil and about 2,827 tcf for gas. (This estimate includes Iran, which holds about 158 bn bls of oil and 1,201 tcf of gas. This suggests that the Caspian’s oil and gas potential, while far from negligible, can hardly threaten that of its not-so-distant neighbour – the Persian Gulf.

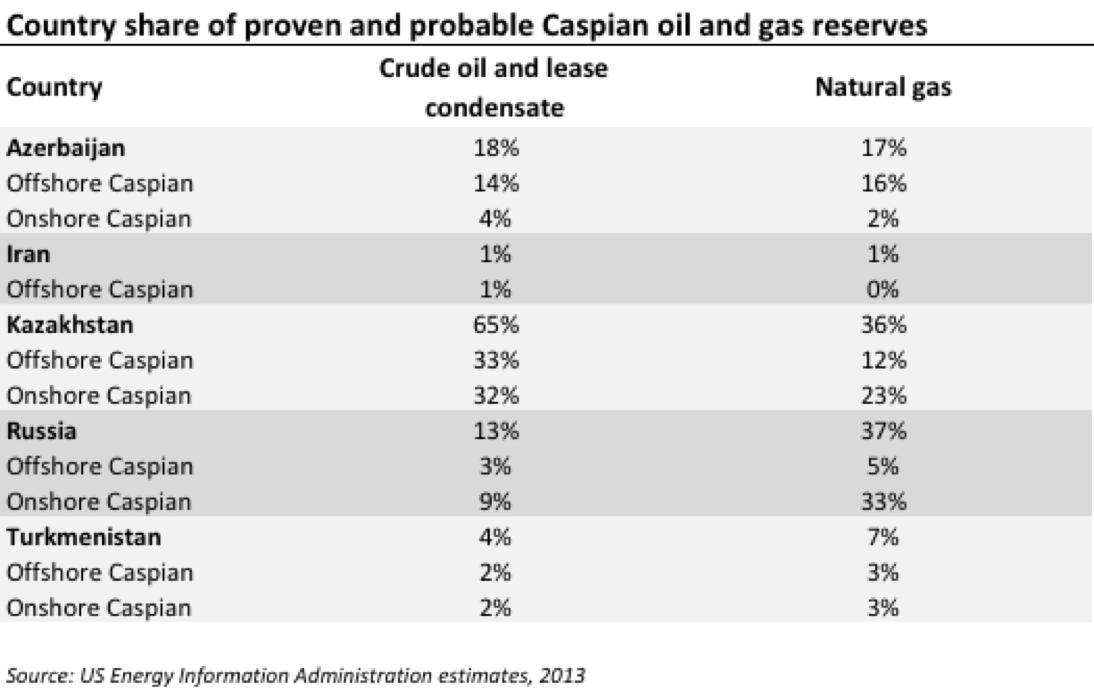

Interestingly, Iran’s Caspian reserves are relatively very small and dwarfed by the shares of the other littoral countries. Kazakhstan has the lion’s share in terms of oil, and it is on par with Russia with respect to natural gas.

‘Project from hell’

The region’s hydrocarbons endowment has been a mixed blessing – as the Kashagan oil field demonstrates. What should have been one of the most attractive and profitable projects in a generation turned into a headache for its investors.

The field was originally scheduled to enter production in 2005, but this start date was continually pushed back by a series of technical and environmental glitches. Commercial output began only at the end of 2016, meaning that the investors missed out on several years of high oil prices.

The Kashagan field is described as one of the most complex projects in the world. Specialists familiar with its conditions have called it “the project from hell.” The field lies in very shallow waters that freeze over for about five months each year. The geology is extremely complex. The oil deposits have large sulphur concentrations and contain many pockets of natural gas under very high pressure. The result has been significant cost overruns and disappointment to the Kazakh government, which expected major tax revenue to flow from the project as soon as 2005.

More broadly, the Caspian Sea is a costly region for oil and gas because of the need for infrastructure to move those resources to distant markets. On top of this, transit fees, winter freezes, regulatory uncertainties and, more recently, rising security risks all inflate investment and operating costs.

Wider conditions

In due course, new developments emerged that further diminished the international competitiveness of the Caspian oil and gas – whether from an investment perspective or from changing perceptions of its potential to enhance the security of energy supplies to Europe and the U.S.

Today’s oil and gas prices are well below their levels of a few years ago, imposing strict discipline on investors in terms of capital allocation. They have also caused deep economic pain among the oil- and gas-dependent Caspian economies, whose growth has suffered from of the loss of export revenue.

The sanctions on Russia and Iran have not helped either, especially given the economic interdependency of the Caspian states. It is therefore no wonder that Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Russia decided to join forces with OPEC in December 2016 to implement production cuts in hopes of putting upward pressure on oil prices – an effort that has yet to bear fruit.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is getting closer to achieving its desire of energy self-sufficiency, thanks to the shale revolution. The EU is also enjoying the repercussions of that revolution on natural gas supplies and prices, benefiting from intensifying competition between major producers, especially in the light of large gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean, right at Europe’s doorstep.

Of course, China’s appetite for energy can help make up for diminished Western demand, but catering to the Chinese market will also require the development of new transport infrastructure. Further, just as consumers do not want to depend on one or a few suppliers to meet their energy needs, producers do not want to be at the mercy of a single customer, preferring to maintain a diversified market base.

Competition

Relations between the Caspian states remain in flux, oscillating between collaboration and competition, friendly statements and accusations – though the latter seem more prominent given the prevailing atmosphere of mistrust. Russia’s cutoff of gas imports from Turkmenistan, Turkmenistan’s dispute with Iran over gas payments, and Iran’s threats that the Trans-Caspian pipeline would damage the “friendly” status of the Caspian are just some recent examples. Each state has its own needs, interests and priorities that often clash with those of its neighbors. Iran, for instance, gets little oil or gas production from the Caspian, while Azerbaijan is fully reliant on it.

The drastic changes in global energy markets and the tight economic situation in each of the Caspian states argue for closer regional cooperation. Progress on the legal status of this body of water would be a major step in the right direction, while a breakthrough could potentially open a new chapter for the region. But it is far from a sure thing that common sense will prevail in an increasingly competitive global energy market.

- Most offshore oil reserves are found in the northern part of the Caspian Sea, while the bulk of offshore natural gas reserves is in the south (EIA)

- One of the biggest production sharing agreements, the so-called “contract of the century,” was signed by Azerbaijan in 1994 with a multinational consortium of 11 foreign oil companies from seven countries

- The Caspian Sea also contains valuable fishery resources, including 90% of the world’s stock of sturgeon

- The BTC pipeline runs for 1,768 kilometers from the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli oil field in the Caspian Sea to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. The route includes a 443 km segment in Azerbaijan, 249 km in Georgia, and 1,076 km in Turkey. Since it became operational in 2006, the pipeline has carried about 2.61 bn bls of oil that were loaded on 3,425 tankers (BP)

- Turkmenistan is one of the most energy-dependent economies in the world, with the hydrocarbons sector accounting for half of gross domestic product, more than 90% of exports, and more than 80% of fiscal revenue (World Bank)

- In 2009, part of the Gazprom-operated Central Asia-Center pipeline that runs from Turkmenistan to Russia exploded. Each country blamed the other for the incident

The article was first published in Geopolitical Intelligence Services