Dr Gavin Graham

In the hope of getting a better insight into how the future might pan out, it is of interest to compare the oil price crashes of the past with the situation we find ourselves in today. While there are clear similarities, particularly with the “oil glut” of 1986, there are a great many more differences, lending weight to the argument that the present oil crash may indeed be ‘lower for longer’. The oil price continues to be driven by the supply-demand fundamentals but the dynamics that shape those fundamentals have changed – perhaps for good.

Film buffs will be aware that Oct 21st was “Back to the Future Day” – the day when, in 1985, Doctor Emmett Brown and Marty McFly planned to travel forward in time. Pushing the link perhaps more than it deserves, it is of interest to note what differences they might have seen.

Being of a scientific bent they might be interested, as many analysts have of late, to compare the oil price shock of 1985/86 to the situation we find ourselves in today.

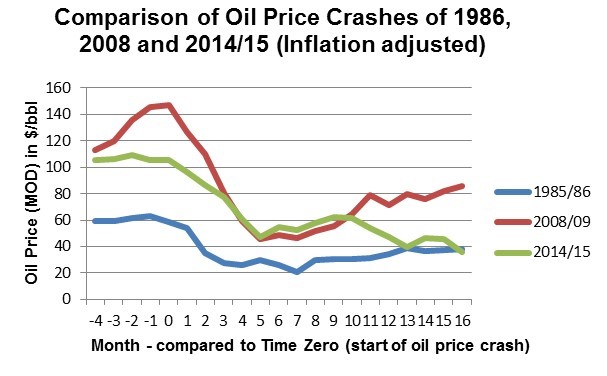

The two charts above compare the current situation with earlier oil price crashes. The 2008 oil price crash was closely related to the global financial crisis and brought rapid response from OPEC, reducing production quotas by 4.2 million barrels per day (Mb/d) within 5 months of the initial downturn. The second chart shows a closer comparison of the situation today with the 1985/86 oil price crash, in which prices have been inflation-adjusted and normalized to the oil price immediately before the crash.

Certainly there were similarities between the situation in 1985/86 and that of today. In both cases the fight was about market share, as oil prices came under pressure due to new sources of supply and weakening demand. Production growth in non-OPEC countries progressively ate into OPEC share, as US reliance on foreign oil imports significantly reduced – albeit for different reasons.

In both cases the tipping point came when Saudi Arabia abandoned the role of swing producer and went for market share – being the driver behind a 1.5 Mb/d increase in OPEC output in 1986 (from 16.3 to 17.8 Mb/d) and almost exactly the same in 2015 (from 30 to 31.5 Mb/d), although this time supported by Iraq. Thus while, according to Baker Hughes, US oil rig count has dropped nearly 65% to just 541 in little over a year, Saudi rigs increased by 15% to 154 during the same period. And in both cases, 1986 and 2015, reduced revenues seriously impacted the exporting countries and divided OPEC.

OPEC met twice during the early part of the 1986 crisis, in February and June 1986, three and six months respectively after prices began to fall, but could not agree on reduced production quotas. Already by the middle of 1986, however, the Gulf buy accutane from canada producers were looking for solutions and by the time they met in August of that year consensus was emerging that an oil price of between $17 and $19/barrel might be acceptable to producers and consumers alike. It took a few months more for the details to be worked out but, at its meeting on 19th December 1986, some 12 months into the crisis, OPEC agreed to reduce quotas by 1 Mb/d and oil prices were set on an upward trend.

Earlier in 1986, Sheikh Ahmad Zaki Yamani, the then Saudi oil minister, was quoted as saying: “We want to see a correction in the trends in the market. Once we regain control of the market by increasing our share, we will be able to act accordingly”.

While it may be dangerous to presume the same objectives today, were we to do so it becomes clear that the options open to OPEC today are not so clear-cut. In the two initial meetings held since oil prices began to fall (Nov 2014 and June 2015), OPEC did not propose to cut production and, despite speculation to the contrary, this did not change at the December 4thmeeting, some 15 months after prices began to fall. This in large part reflects the differences between the 1986 situation and that of today.

In 1986 the target of the Gulf producers was the high cost ‘conventional’ non-OPEC oil sector, whereas in 2015 it seems to be the US shale industry, which behaves more like an industrial manufacturing business and responds very differently to the conventional oil sector. In 1986 security concerns in the US and the real threat of tariffs resulting from a meeting between Vice President George Bush and King Fahd of Saudi Arabia in April 1986 played a role in convincing the Saudis to find a solution. Such political pressure is unlikely to be brought on OPEC producers today. In 1986 the OPEC members could agree on an oil price that suited both producers and consumers ($18/barrel) to end the oil crisis, whereas today the price is driven entirely by market forces. And in 1986 OPEC could gather support from others (Mexico, Norway and even Russia), whereas the possibility of such support is not (yet?) so clear today.

With Chinese growth slowing down, oil inventories running some 110 Mb/d above historic levels and Iran waiting in the wings, it is unlikely that the market today will readjust naturally in the short-term. Once again, it will require a calculated decision from Saudi and the other Gulf producers to take significant oversupply off the market.

They clearly have an incentive to do this. But the key question remains when will they blink. At current oil prices Saudi Arabia has to support its budget by upwards of $2 billion a week – to which must be added the significant costs of the military action in Yemen. With financial reserves estimated at some $746 billion a year ago – now reduced by some estimates to below $600 billion – the Kingdom could continue on the current strategy for two to three years, but not without significant pain. And the level of pain is far greater for other OPEC producers, most notably Venezuela, Algeria and Iraq, leading to concerns that instability within oil exporters may ultimately impact supply more than the targeted demise of the US tight oil producers or the $300 billion removed from investment plans by the majors.

Once OPEC members believe that the tide has turned on oil shale production in the US, they have it in their hands to take 1 to 2 Mb/d off the market. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) has reported a drop in US onshore production in the last three months. US rig count and storage have leveled off, but the question remains: for how long, and how irreversible, given the generally held belief that tight oil production can pretty much be switched on and switched off as oil prices shift.

US tight oil producers are indeed proving more resilient than perhaps anticipated by the Gulf oil exporters:

- Drilling and fracking costs and efficiencies are reported to have improved dramatically over the last year. It can now take as little as eight days to drill a well, down from 30-40 just a few years ago, with cost/foot down by over 40 percent in the Bakken since 2009, and initial production rates following fracking have improved by over 110 percent in the Eagle Ford – with talk now about re-fracking on the basis of detailed ‘reservoir’ modelling.

- While many US onshore producers may fail to re-emerge from the next debt redetermination in April 2016 – and the tight oil sector as a whole likely needs $65-70 for a sustainable future – the play ‘sweet spots’ may still be viable at $30/barrel.

- Up to 1 Mb/d production is reported to have been drilled but not fracked.

The jury remains decidedly out as to how fast and to what level oil prices will come back (note that, after the 1986 “oil glut”, prices stayed depressed for 20 years).

If they had indeed emerged thirty years later on ‘Back to the Future’ day, Doctor Emmett Brown and Marty McFly would have noted Bob Dylan playing at the Royal Albert Hall and a new James Bond movie about to premiere in Leicester Square. They might have been excused for believing that remarkably little had changed. Some things have however changed, quite possibly forever. Oil price dynamics are one of these.