Lord Howell

Here is a tricky international dilemma. What does a country do when it has two powerful friends with whom it wants — and needs — to have ever closer and better relations, but when unfortunately the two countries concerned dislike and even fear each other intensely?

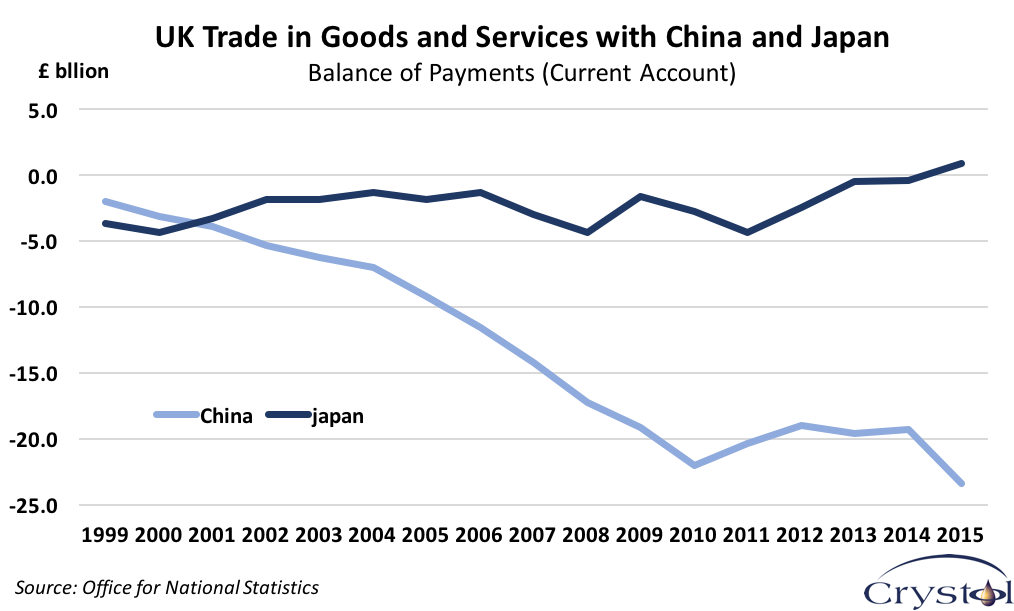

This is precisely the United Kingdom’s position in the case of China and Japan. As the U.K. looks outside Europe to expand new markets, and new sources of investment, following the Brexit decision to leave the European Union, it becomes increasingly important to be on excellent terms with both these key Asian and global powers with their colossal consumer markets.

But for the U.K. this means maintaining a delicate and skilled balance to avoid accusations of unduly favoring one source or the other, or letting down friends or similar complaints.

In recent weeks Japan has clearly been the favored one in British minds. This is because the Japanese giant Softbank has arrived with a substantial inward investment bid to purchase a leading British company, ARM Holdings, the world-beating chip manufacturer. This has come at just the right time psychologically when fears had been growing that Brexit would deter foreign inward investment, on which the British economy relies.

In recent weeks Japan has clearly been the favored one in British minds. This is because the Japanese giant Softbank has arrived with a substantial inward investment bid to purchase a leading British company, ARM Holdings, the world-beating chip manufacturer. This has come at just the right time psychologically when fears had been growing that Brexit would deter foreign inward investment, on which the British economy relies.

To the relief of the new British government, the billions from Japan seem to prove these fears unfounded and that the U.K. still exerts its powerful attractive charm to world investors. The deal is doubtless also a shrewd and timely one when the pound sterling has been dropping.

This has also acted as a strong reminder of the central role Japan has long played over many years in British business, including of course in the revival of its highly successful motor industry, in the economy of South Wales, in electronics, in railway equipment and in many other areas.

But back last year it was a different picture. The U.K., it seemed, was going all out to cultivate its Chinese connections, leading the support for a new Chinese development bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, inviting Chinese involvement in British railway and infrastructure modernization and welcoming the Chinese into its revived civil nuclear program. At that time the British appeared almost to have forgotten that Japan, not China, had long been their best friend in Asia, and that the U.K. had long been regarded as Japan’s best friend in Europe.

Instead all the talk was of China as the U.K.’s new “best friend” and partner, with special privileges for Chinese banks and Chinese business visitors, placing them in a more favoured position not just than Japanese travelers to the U.K., but also giving them a better deal than visitors even from other key countries such as India — supposedly a close Commonwealth ally.

British eyes and hopes, it appeared, were firmly focused on China’s immense plans for covering Central Asia with a maze of new roads, railways and gas pipelines — vast projects in the construction and financing of which the U.K. was determined to be involved.

No wonder there were alarm signals in other capitals, including Tokyo, that the U.K. might be, so to speak, spending too much time with China at the expense of ties with other old friends.

But now the balance has been restored. Japan, or at least Japanese business, has shown that it remains a true ally and, as the saying goes, a friend in need is a friend indeed.

Two other factors may have helped balance out a tricky situation. First the Chinese response to the Hague-based Permanent Arbitration Court’s ruling over the Scarborough Shoal, and by implication other islets and rock formations in the South China Sea — namely to turn it down flat — has been worrying for those in the West doing business with China.

Second, the planned new French-designed nuclear power station in the U.K. at Hinkley Point C, for which Chinese financial support was so badly needed, looks less and less likely to be built, thanks to spiraling subsidy estimates, untried technology and construction costs. The truly important projects in the British new-build civil nuclear program lie elsewhere (in North Wales and in Lancashire) and both of these rely on Japanese-led consortiums.

All in all it could turn out that the dilemma is not so difficult. The U.K. really has no choice but to build the strongest possible ties with both countries. Modern supply chains now wind across the digitalized world, globalizing not only trade but actual production processes. In these new circumstances no major trading nation, and especially not the U.K., can afford for one moment to be anything but very closely linked to both China and to Japan at all levels, from small business and cultural ties up to the handling of major global issues, like climate change, security, anti-terrorism and world health.

Best of all would be if one day Japan and China could sink their differences despite the horrific legacies of the 20th century and get on as neighbors, just as the Europeans have done.

That may look unlikely now but it would be a clear win-win situation all round for global prosperity and peace — in fact for everyone.

The article was originally published in The Japan Times.