Lord Howell

The energy scene is usually regarded as too complicated for everyday discussion — best left to technicians, scientists, government officials and giant corporations as long as the lights stay on, machinery turns, cars and buses roll and the thousand and one needs of a largely electric world are satisfied.

Yet beneath the surface lurk dark forces that can topple governments, destroy nations, trigger massive violence, start wars, promote disasters and inflict unimaginable suffering.

The energy year just ending had all these features.

Directly or indirectly the big shifts in the global production pattern of hydrocarbons — oil, gas and coal — and changing energy technologies have contributed to further upheaval in an already chaotic Middle East, further threatened the world environment, stirred civil unrest in both Europe and Asia, and sent shivers through governments and the world’s financial systems.

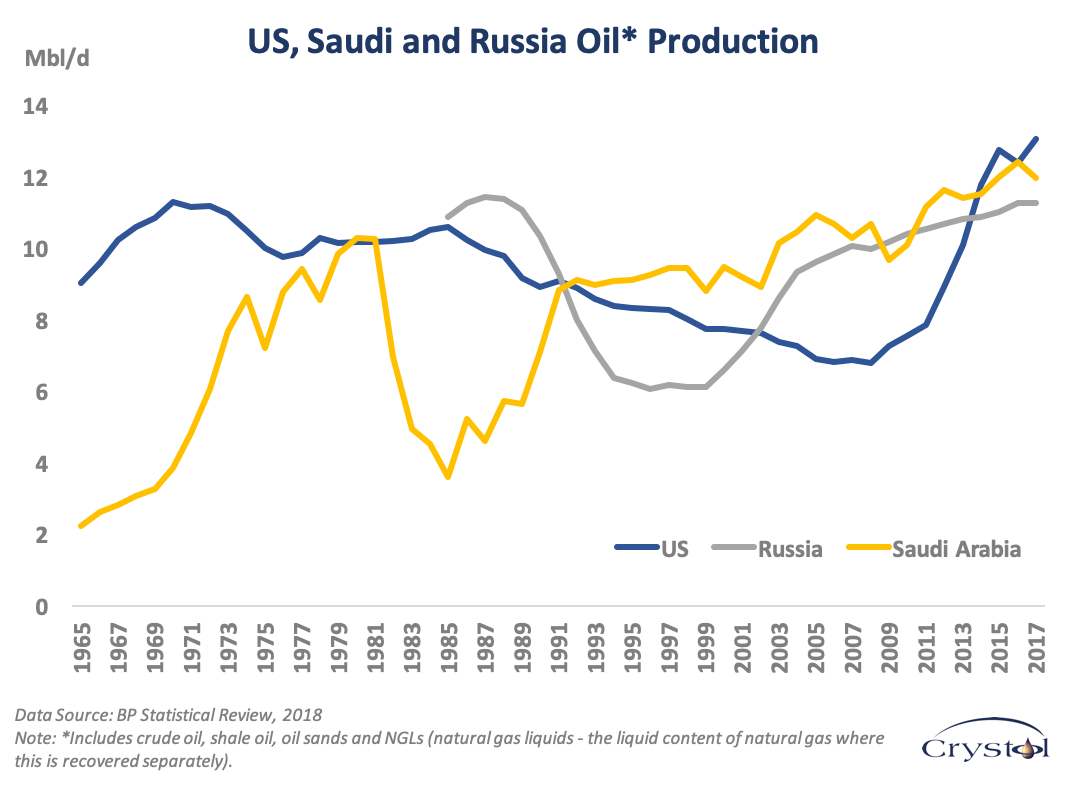

By far the biggest immediate feature, although scarcely commented on, is the soaring level of U.S. oil and gas output, making the United States the world’s No. 1 oil and gas producer, challenging the other two energy giants — Russia and Saudi Arabia — sending cracks through the once all-powerful OPEC oil cartel, adding to Saudi difficulties and piling more misery on ill-governed Venezuela, as crude prices slide downwards.

There was once a time when Western reliance on Arab oil, and particularly the high level of U.S. oil imports, underpinned relations between the West and the Gulf kingdoms and emirates. Back in the early 1980s U.S. Energy Secretary James R. Schlesinger was telling this author, then his opposite number in the United Kingdom, that if ever American oil imports exceeded 40 percent of its daily needs, American entanglement in the oil-producing countries of the Middle East would deepen dramatically.

Imports duly rose to 40 percent, and then at one stage 60 percent, of U.S. oil consumption, with many repercussions on U.S. foreign policy and activity. But now, incredibly, it is zero — indeed less than zero — as the U.S. becomes a net exporter of both oil and gas.

The obvious consequences flow. The U.S. has less reason to be involved in the Middle East or support Saudi Arabia. Conversely the Saudis have to work harder to keep Washington sweet and fulfil President Donald Trump’s wishes, especially when they face general condemnation for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul and when they are bogged down in a miserable proxy war with Iran in Yemen. These American wishes are first to keep the oil price just right and not too high to hurt American consumers (and voters) and not too low to discourage still more domestic shale investment and production.

Second, Trump wants the Saudis and other Arab states to ally with Israel in a general confrontation with Iran — a strategy that is full of danger and making little progress.

Meanwhile Trump’s deep but contradictory impulse — to withdraw America out of the Middle East quagmire — is also driven by the country’s self-contained energy power. Feeling he can safely walk away whenever he chooses no doubt plays some part in his hotly disputed decision to pull troops out of Syria and Afghanistan.

Oil politics plays a cross-over part in the other big energy-related drama of 2018 — namely, the battle against climate change.

The supposed great energy transformation to a carbon-free world is not going well.

In October the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, meeting in Kyoto, warned that even if Paris agreement emissions targets are met it will not be enough to avert severe climate disruption. More recently, at the latest United Nations climate change conference (COP 24) in Katowice, Poland, a hard-won new agreement papered over many disputes and some inconvenient realities.

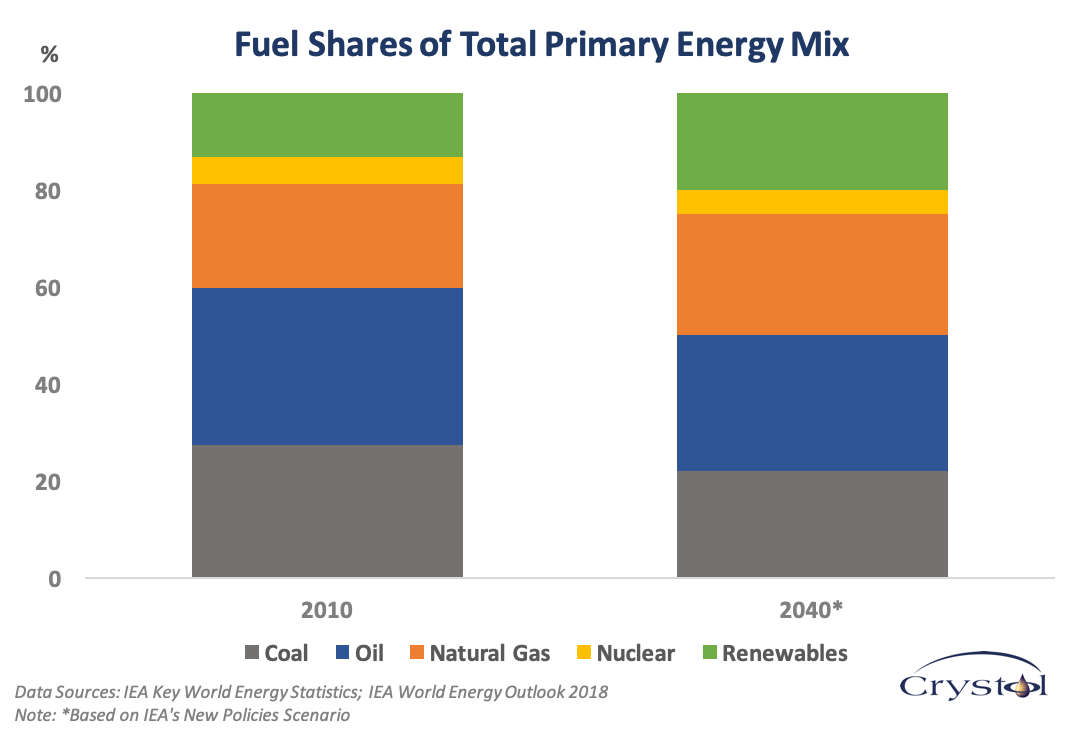

One of these realities is that, despite the growth of renewable energy, and some useful cost declines, oil and gas are set to remain the dominant energy sources. The International Energy Agency’s World Outlook tells us that oil, gas and coal still account for the same percentage of world energy (81 percent) as it did 10 years ago and will still account for 74 percent 20 years from now.

Cheaper oil (in a world with a surplus of both oil and gas) could slow the green changeover still more. As for coal, the biggest consumer, China, having checked coal demand earlier, is now back-tracking by burning more coal and is planning a colossal 220 gigawatts of new coal-burning plants. India, too, although not on the same scale, is staking its cheap energy future on massive coal plant expansion.

Cheaper oil (in a world with a surplus of both oil and gas) could slow the green changeover still more. As for coal, the biggest consumer, China, having checked coal demand earlier, is now back-tracking by burning more coal and is planning a colossal 220 gigawatts of new coal-burning plants. India, too, although not on the same scale, is staking its cheap energy future on massive coal plant expansion.

As for the highest per capita energy consumer, the U.S., President Donald Trump is now encouraging it to expand coal, keep energy cheap and ignore the Paris targets altogether. Meanwhile Russia shows no interest in climate goals as long as it can sell its gas and oil and keep the Kremlin regime afloat.

One more lesson in climate backlash comes from France, where President Emmanuel Macron has had to reverse extra fuel levies intended to curb oil consumption, and make other concessions as well, to prevent further violent rioting both in Paris and right across the nation.

As the renowned energy commentator Nick Butler has observed, (in the Financial Times) the present world’s plan to curb carbon dioxide is just not working. Carbon dioxide emissions are now 40 percent higher than in the year 2000.

There has to be a Plan B. The ugly truth is that the emissions battle will not be won or lost in Europe. It will be won or lost (and at present is being lost) thanks to the energy policies of China, India, the U.S. and Russia.

Only if those can be changed, with the aid of massive advances in technology and science, with lower nuclear power costs, cheaper storage and super-efficiency in energy use, will the real disasters of global warming be contained. Some say they are already with us, as tsunami, hurricanes and earthquakes claim many lives.

So energy policy is in practice dominating geopolitics, dominating daily lives and dominating the future — not so remote and purely technical after all!