Dr Carole Nakhle

The United States has played an important role in the oil markets since the beginning of the oil era nearly two centuries ago. However, its place on the stage has shifted from the center to the wings and back again over the years. In 1880, it accounted for 85 percent of global crude oil production and refining, but rapid growth in domestic consumption had shifted the U.S.’s position from a major net exporter to a net importer by the mid-1950s.

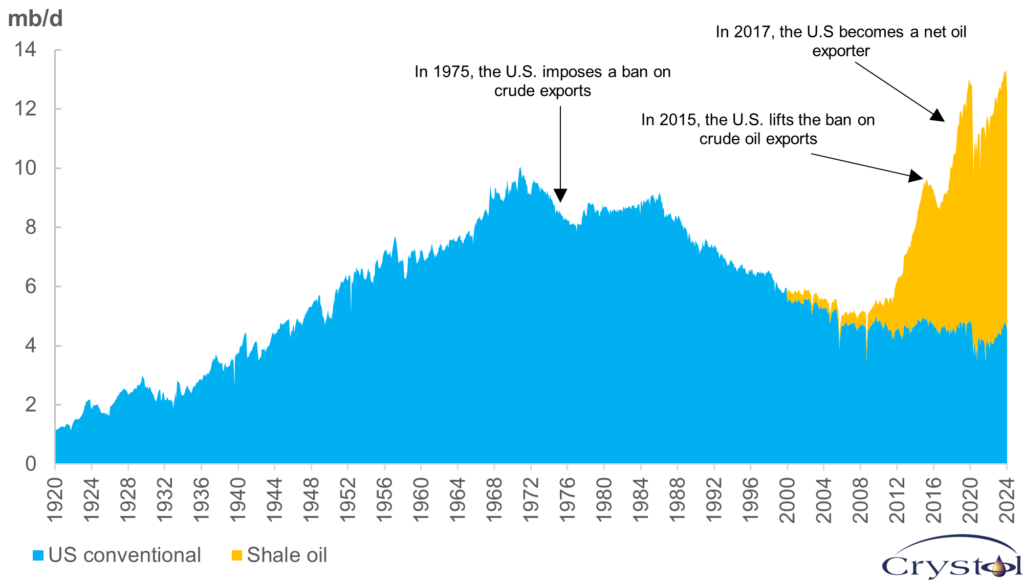

When U.S. conventional oil production peaked in 1972, and the first oil shock struck in 1973, the American people became alarmed by their dependence on oil imports from OPEC countries and the Middle East. So, on November 7, 1973, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced Project Independence, which he put in the same league as the Manhattan Project and the space program. The aim was “the strength of self-sufficiency” in energy – a goal that has been pursued by every subsequent president. It took around 70 years for the U.S. to achieve this, becoming a net exporter of oil in 2018, when it also outpaced both Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest oil producer.

At the heart of that achievement and transformation is U.S. shale oil, a resource long considered uneconomic that became accessible thanks to advances in technologies and higher oil prices. The remarkable success of the shale revolution was heralded by the rise in U.S. natural gas production. While conventional gas production peaked in 1973, thanks to shale, by 2009 the U.S. had surpassed Russia as the world’s biggest gas producer. In 2023 it became the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter in the world, outgrowing Qatar and Australia – two giants of the industry.

While the demise of U.S. shale oil and gas has been predicted many times, the industry has proven resilient even in the face of serious challenges over the years, including the collapse of oil and gas prices during the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent wave of bankruptcies, capital discipline and consolidations. The climate change agenda, aggressively pursued by the Biden administration, has also diminished enthusiasm for the sector.

Several factors determine the outlook for U.S. shale oil and gas. While prices will continue to play an important role, in the short to medium term the outcome of the U.S. elections will be key. President Joe Biden and presidential candidate Vice President Kamala Harris are widely perceived as unfriendly to the oil and gas industry. One week after taking office, the President Biden signed the “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad” to ban new oil and natural gas leasing on federal lands and waters; accused oil and gas companies of “war profiteering” in 2022; and then in 2024 announced a temporary pause on pending approvals of LNG exports to assess their environmental and economic impacts.

U.S. crude oil production

Data source: EIA

Vice President Kamala Harris has also championed the green cause throughout her political career. As a senator, Ms. Harris co-sponsored the Green New Deal, a resolution that emphasizes the need to transition to clean and renewable energy, create green jobs and address the impacts of climate change. The Green New Deal, while not legally binding, reflects the Democrats’ policy of shifting away from fossil fuels, including oil. During her previously unsuccessful campaign in 2020, she pledged to ban fracking.

On the other side of the spectrum is Republican Party presidential candidate Donald Trump, who is not seeking U.S. energy independence but eyeing energy dominance. “We will drill, baby drill,” he said in his speech at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee on July 18. Trump said increased domestic production of oil and gas would lead to a “large-scale decline in prices,” adding, “We will do it at levels that nobody’s ever seen before.”

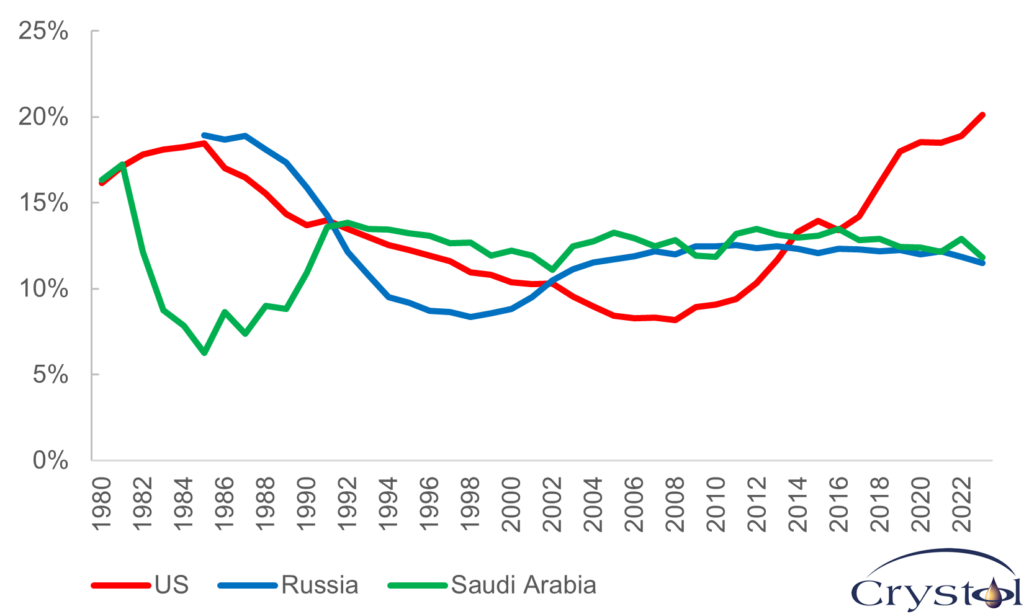

Powerful producer

The U.S. sits on the ninth-largest proven oil reserves (4 percent of global proven), after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Iran, Iraq, Russia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, and fifth in terms of proven gas reserves (7 percent of global proven) after Russia, Iran, Qatar and Turkmenistan. Yet despite its smaller reserves, it has bypassed all competitors and is currently the world’s largest oil and gas producer, accounting for 20 and 25 percent of global production respectively. This achievement illustrates the resilience and innovation of a competitive market structure where private companies – small and large alike – are engaged in healthy competition.

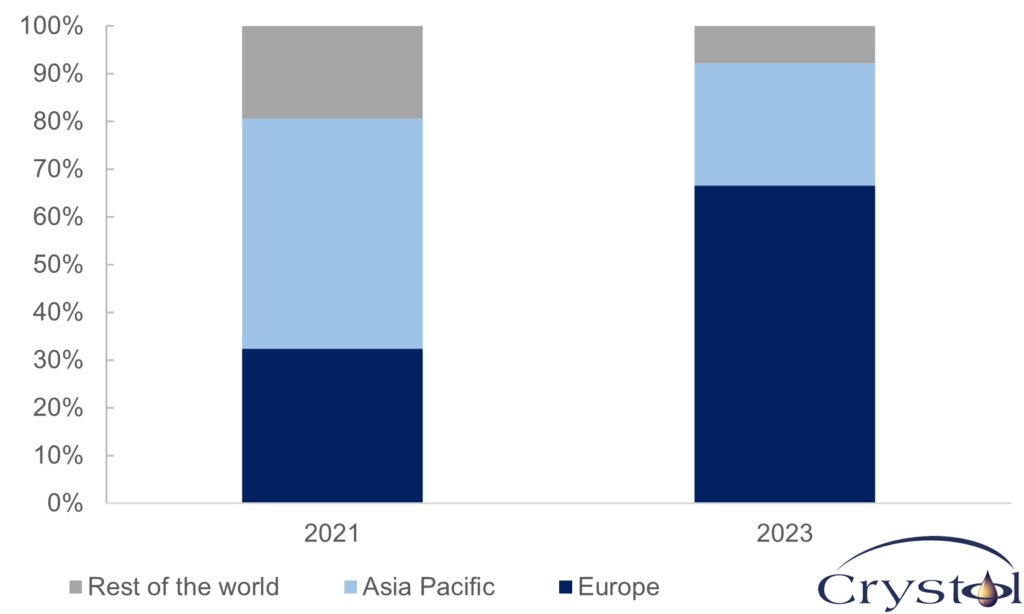

U.S. LNG exports by destination

Data source: Energy Institute

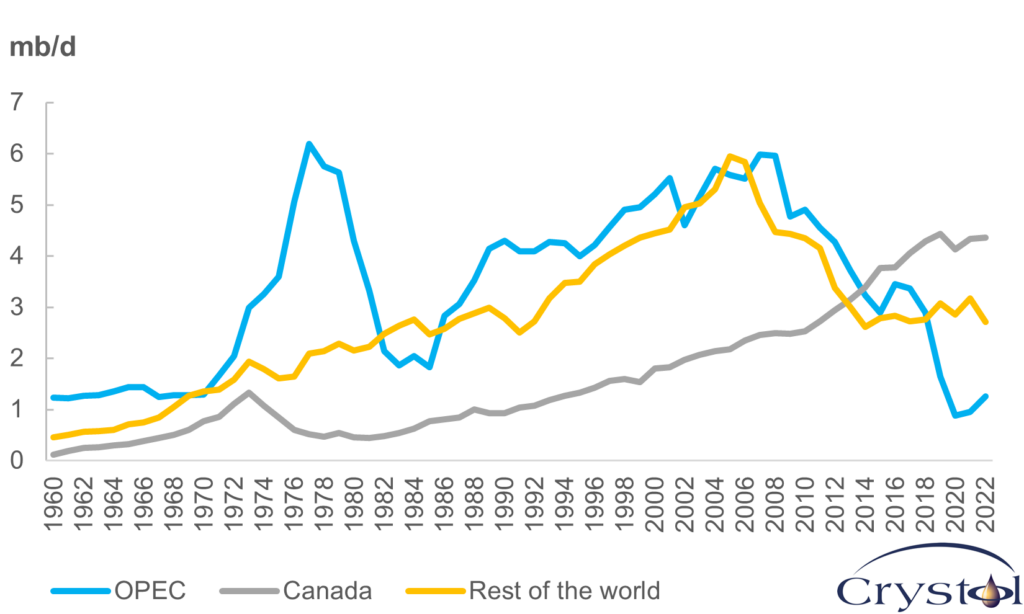

The shale revolution has disrupted the global oil and gas markets. In five years, between 2014 and 2019, U.S. oil production increased by 5.3 million barrels per day (mb/d), effectively adding the equivalent of one Canada (the world’s fourth-largest oil producer after the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia) to the market. Over the same period, U.S. gas production grew by 223 billion cubic meters (bcm), comparable to adding another Iran (the world’s third-largest gas producer after the U.S. and Russia) to the market. This surge in output has benefited not only the U.S. economy and its quest for energy independence, but has boosted global energy security by providing customers around the world with a more diverse source of supplies.

For example, it was U.S. LNG that largely helped Europe break Russia’s grip on the European energy market – a process that was gradually unfolding even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. In July 2018, the European Union and the U.S. entered a strategic cooperation on energy when then President Trump and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker agreed to strengthen EU-U.S. strategic cooperation with respect to energy, including greater LNG imports to enhance Europe’s energy supply security and reduce the region’s dependence on Russia. However, the U.S. contribution became most notable after Russia unleashed full-scale war on Ukraine. Before the war, the EU absorbed 32 percent of total U.S. LNG exports. In 2023, that share more than doubled.

The rise of U.S. shale oil has also been a key driver shaping OPEC output decisions. In 2014, OPEC for the first time in its history decided to abandon any output restrictions, allowing all members to produce at full capacity. The hope was that a subsequent decline in prices would kill off high-cost producers – in particular shale, which had previously required prices well above $80 a barrel to break even. However, OPEC had underestimated the remarkable efficiency gains that shale had achieved since the beginning of the revolution, and the industry’s ability to rapidly slash costs.

Global oil market share

Data source: Energy Institute

Recognizing that shale was not going to go anywhere anytime soon, OPEC soon abandoned its unrestricted output policy and in December 2016 created a bigger alliance – what became widely known as OPEC+, where a group of non-OPEC producers led by Russia joined forces with OPEC to safeguard market share. When that cooperation was first announced, it was originally planned for six months. However, as shale has outlived expectations, it has also lent a longer lifeline to OPEC+.

Today, oil supply is a story of two powers: OPEC+, and non-OPEC+ led by the U.S. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects non-OPEC+ output to rise by 1.5 mb/d, which will boost the global oil supply to a record 103 mb/d in 2024. For next year, global supply growth is projected at a stronger 1.8 mb/d, with non-OPEC+, mainly the U.S., along with Canada, Guyana and Brazil, leading the gains for a third consecutive year, adding 1.5 mb/d.

Underestimated resource

A look at forecasts made since the beginning of the shale revolution shows how much the industry’s resilience has been underestimated. In 2008, the IEA released its oil supply projections without even mentioning U.S. shale oil; the agency expected U.S. oil production to continue its long-term downward trend, reaching 6.5 mb/d in 2030. Even in 2014, when the IEA recognized the contribution of U.S. shale oil to “temporarily” boosting global supplies, it still foresaw a “tailing off of U.S. production” in the 2020s, while non-OPEC supply would also flatten and then start to fall. Those projections were wrong, and a few years later the agency made a notable about-face in its position towards shale. Now it does not expect production to peak until after 2030.

Compared to conventional oil and gas operations, shale is a recent trend. While at the molecular level, it is of the same stuff as conventional hydrocarbons, its extraction is quite different, resulting in different economics and industry structures. Furthermore, production has largely been confined to the U.S., unlike conventional oil and gas, which is a global business. This is part of the reason for the poor track record in forecasting the sector’s performance.

Oil imports from the U.S.

Data source: EIA

The industry, once dominated by small, independent companies, has now seen a wave of major oil and gas players get in on the shale act, trying to capitalize on the robust opportunities offered by the abundant resources. Since July 2023, companies like Exxon, Chevron and Occidental Petroleum have announced $194 billion worth of deals across the U.S. shale sector – almost triple the amount compared to the previous 12 months.

But the impact of such consolidations remains unclear. An industry survey on the impact of consolidations in U.S. shale production in the next five years found that 48 percent of respondents expected “slightly lower” output, compared to 22 percent who foresaw “no impact” and another 22 percent who expected output to be “slightly higher.”

Outlook for U.S. shale

Meanwhile, various current industry reports expect U.S. shale growth to continue but at a slower pace. Numbers differ notably: The IEA expects the U.S. to be the largest contributor to global oil supply in the medium term, adding 2.1 mb/d by 2030, but it also notes that annual increases across all shale basins are expected to decline from 9 to 3 percent, with capital discipline, the recent wave of consolidations, and challenges to productivity and profitability metrics limiting growth. OPEC also expects the U.S. to contribute nearly half of the 7 mb/d additions from non-OPEC supply to the global markets between 2022-2028, but also forecasts U.S. shale production will peak by the end of this decade.

In contrast, U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) continues to be optimistic, predicting U.S. production to remain historically high through 2040 as exports of finished products grow in response to rising international demand.

In terms of natural gas, the International Gas Union expects a large amount of U.S. LNG capacity to be added by 2028, and energy major BP expects the U.S. to contribute more than half of the global LNG supply increase by 2030, with the remaining growth driven largely by the Middle East.

Scenarios

Most likely: The U.S. shale sector continues to play an important role

Oil and gas prices, cost inflation and technology will continue to shape the outlook for shale in the foreseeable future. Prices, in particular, have a more immediate impact on the shale industry than they do on conventional oil and gas, given the much shorter lead time between investment and production in the case of shale.

However, a key variable that will play a decisive role in the short to mid-term is government policy, particularly if there is a major change in Washington that has a big impact on investment sentiment. For instance, the 2024 temporary ban on the issue of licenses for new LNG export terminals announced by the Biden-Harris administration caused uproar in the industry and from its backers. Mike Sommers, the President and CEO of the American Petroleum Institute (API), the representative organization for the U.S. oil and gas industry, called on the U.S. government “to stop playing politics with global energy security.” And Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co in a letter to shareholders argued that “trade is realpolitik, and the recent cancellation of future LNG projects is a good example of this fact.” He added that “the projects were delayed mainly for political reasons – to pacify those who believe that gas is bad, and that oil and gas projects should simply be stopped. This is not only wrong but also enormously naive.”

The potential arrival of a Trump-Vance administration, bringing with it much stronger sympathy for the oil and gas industry, would inject greater optimism into the sector and encourage further investment, assuming prices remain supportive. President Trump’s pro-oil and gas views are widely known. His running mate, Senator J.D. Vance, has echoed them in his words and actions since he joined the Senate in 2023: He was a supporter of “Protecting Our Wealth of Energy Resources Act of 2023” or the “POWER Act” – a bill that requires the president and federal agencies to obtain the approval of the U.S. Congress before prohibiting or substantially delaying certain new energy or mineral leases or permits on federal lands. Mr. Vance also wants tax rebates for gasoline powered cars instead of electric vehicles.

Thus, if the Republicans win the race to the White House, investment in U.S. oil and gas in general and shale in particular will receive a boost that could translate into stronger growth than many currently expect. If, however, Democratic nominee Kamala Harris wins, it is instead more likely that the trend of the last few years will continue. But however the 2024 presidential election ends, shale has already proven that it will be center stage for at least the next couple of decades.

Facts & Figures

- On October 19, 1973, Arab oil producers stopped oil exports to a group of countries led by the U.S., which supported Israel during the Yom Kippur war with Egypt. Combined with a series of production cuts, the embargo caused oil prices to nearly quadruple within a few months.

- In 1975, the U.S. Congress passed the 1975 Energy Policy and Conservation Act, which directed the president to ban crude oil exports.

- The combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) that took off in the early 2000s has allowed oil producers to unlock previously inaccessible oil and gas resources that remained trapped in shale source rock and did not migrate and accumulate in typical reservoirs closer to the Earth’s surface.

- The U.S. Energy Information Administration expects the U.S. to remain a net exporter of petroleum products and natural gas through 2050.

- BP expects the U.S. and the Middle East to be the primary global hubs for LNG exports, supplying around half of the world’s LNG by 2030, up from about a third in 2019.

- In 2023, ExxonMobil announced it will double production from its U.S. shale assets over the next five years, leveraging innovative technologies.

Related Analysis

“The globalization of gas“, Dr Carole Nakhle, May 2024

Related Comments

“Growth outside OPEC+ robust“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

“Carole Nakhle, Chief Executive Officer at Crystol Energy discusses projections for the United States oil market“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Mar 2024