Dr Carole Nakhle

Nuclear power offers several undeniable advantages over renewable energy, particularly regarding the scale and reliability of electricity generation. This resilience makes the need for backup generation unnecessary even when the sun is not shining or the wind is not blowing. Yet zero-emission nuclear power receives scant attention in the ongoing debate about the energy transition.

The European Union, the region most aggressively pursuing ambitious climate targets, hesitantly acknowledged nuclear energy in its 2022 “sustainable investment taxonomy.” This designation is intended for projects that will aid the transition from fossil fuels and ensure Europe achieves climate neutrality by 2050. The taxonomy ranks nuclear alongside natural gas – a hydrocarbon – describing both as “transitional activities” aimed at facilitating a shift away from more harmful energy sources like coal and toward a predominantly renewable future, although with “strict conditions” applying. Such a limited acknowledgment is unlikely to stimulate significant investment in nuclear power.

Despite the advent of nuclear energy nearly 70 years ago – when the first nuclear plant began operating in Obninsk, Russia – it currently accounts for the lowest share, a mere 4 percent, of the global primary energy mix, and represents only 9 percent of electricity generation. Even at its peak in 2001, nuclear energy represented less than 7 percent of the global energy framework. In contrast, the share of modern renewable energies surged from 1 to 8 percent between 2001 and 2023.

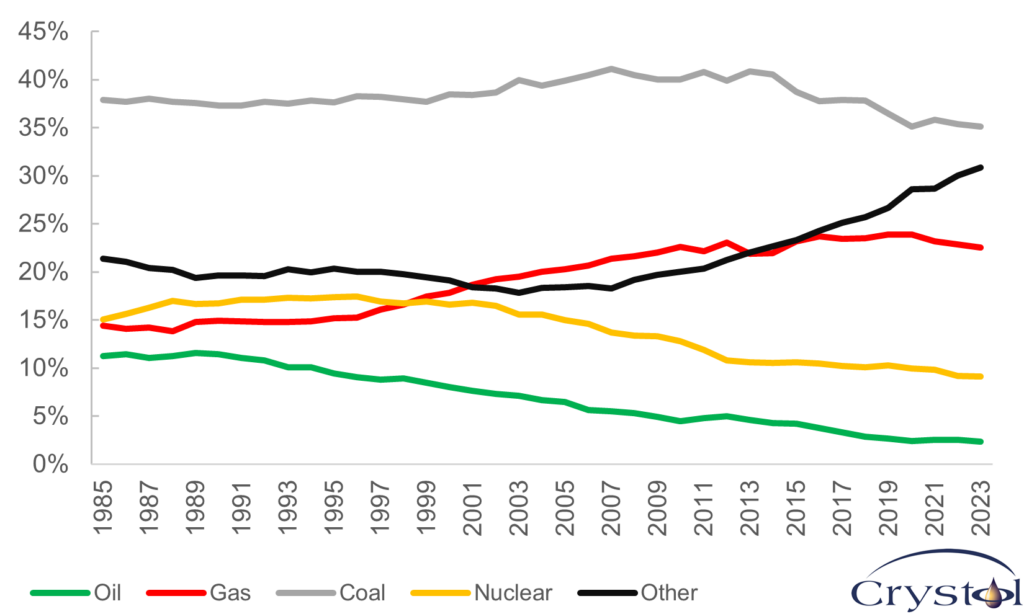

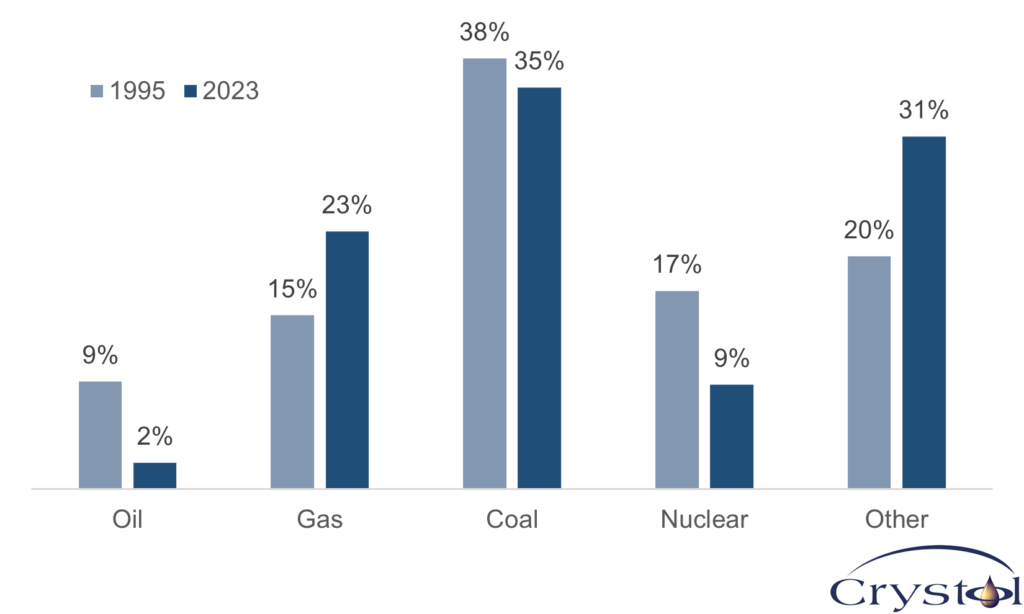

Nuclear power generation, which peaked at nearly 17.5 percent of the power sector’s global total in 1995, has followed a declining trend similar to that of oil. Conversely, natural gas and renewables like wind and solar have made substantial gains, rising from 15 percent and 20 percent, respectively, in 1995, to 23 percent and 31 percent, respectively, by 2023.

While a shift in energy sources is occurring, it appears the world is mainly replacing one fossil fuel with another and one green energy source for another. This is not indicative of a successful energy transition; on the contrary, the target outcome seeks to replace fossil fuels with truly sustainable and emissions-free energy options.

Electricity mix evolution globally

Source: Energy Institute (2024)

Nuclear trends

On a regional scale, trends diverge. While some corners of the globe have embraced nuclear power, others have abandoned it. Until 2016, Europe was the dominant player in the nuclear energy market, generating 36 percent of global nuclear power. Today, however, Europe ranks third, holding a 27 percent share, following North America at 34 percent and the Asia-Pacific region at 29 percent. In Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, nuclear energy usage is minimal, accounting for an aggregate share of just 2.5 percent.

But nuclear energy has recently witnessed a resurgence in support. In late 2023, for the first time at a Conference of Parties (COP, the highest-level decision-making body of the signatories of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), around 25 countries, including several European states, backed the Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy capacity by 2050.

At the same time, the broader consensus takeaway from the meeting, known as the Global Stocktake, called for accelerated deployment of nuclear energy, prompting the International Atomic Energy Agency to describe these events as “nothing short of a historic milestone and a reflection of how much perspectives have changed.” Nevertheless, this renewed interest in nuclear energy remains dwarfed by the extensive financial support consistently enjoyed by renewable energy, which is regarded as the safer, more accessible alternative.

Share of fuels in power generation globally

Source: Energy Institute (2024)

The debate surrounding nuclear energy is set to continue, with regional disparities persisting. Countries pursuing nuclear electricity generation will advance at markedly different rates, with several projects stalling in the planning phase. Overall, as the energy transition unfolds, nuclear power will likely remain a laggard despite its reliability and “green” potential.

Asia powering ahead

Asia-Pacific is currently leading the way in nuclear power development, accounting for 64 percent of all nuclear reactors under construction worldwide. China is at the forefront of this expansion, although nuclear power currently contributes less than 5 percent to its total electricity generation mix. Beijing aims to boost this figure to 10 percent by 2035 and 18 percent by 2060, which, if achieved, would significantly elevate global nuclear usage.

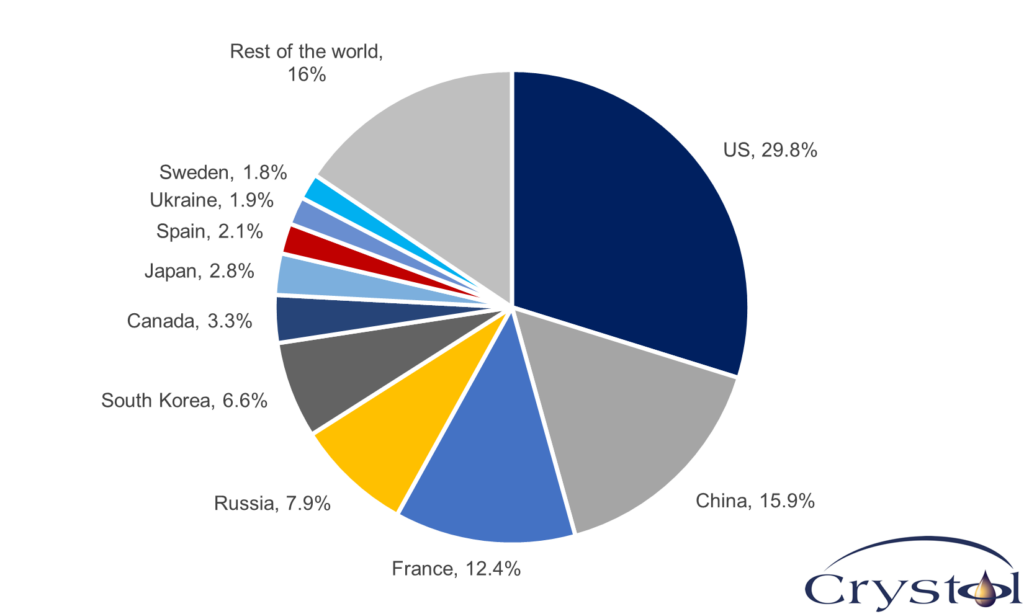

In terms of numbers, China generated around 435 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity from nuclear power in 2023, second only to the United States, where nuclear energy accounts for 817 TWh or 18 percent of the national power mix. France, the largest producer of nuclear power in Europe and the world’s largest net exporter of electricity, generates around 338 TWh each year through nuclear power, more than 65 percent of the country’s electricity mix – more than any other nation.

China currently boasts more nuclear reactors under construction than any other country and is on track to become the leading nuclear power producer by 2030. While the U.S. maintains the largest nuclear fleet, with 94 reactors, it took nearly 40 years for the country to add the same amount of nuclear power capacity that China achieved in just one decade.

Nuclear power generation by country

Source: Energy Institute (2024)

South Korea, Asia-Pacific’s second largest consumer of nuclear power, produces 180 TWh annually – 29 percent of its energy mix – and since Yoon Suk Yeol moved into the president’s office in 2022, the country is now targeting a minimum nuclear share of 30 percent by 2030. That is a sharp reversal of the decision of Moon Jae-in, the former president elected in 2017 on a campaign to phase out nuclear energy.

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident, triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, radically altered Japan’s energy landscape. By May 2012, all 54 of the country’s commercial nuclear reactors – responsible for generating about 30 percent of its electricity – had been shuttered. With few domestic energy resources to rely on, Japan was compelled to increase its dependence on fossil fuels imports, heightening its vulnerability in terms of energy security. More recently, the country has gradually reintroduced nuclear power, anticipating that it will contribute around 20 percent to its electricity generation mix by 2030, up from just 8 percent today.

India, too, is positioning itself as a significant nuclear-energy player in the region, aiming for a 70 percent increase in its nuclear power capacity by 2029, up from its share of 2 percent, or 48 TWh currently.

Wider interest in nuclear energy

Apart from Asia-Pacific, ambitious nuclear power targets are being set primarily in Europe. The United Kingdom, for instance, announced in January 2024 its largest nuclear expansion since its initial rollout, with plans to quadruple nuclear generation by 2050. The Czech Republic in July selected South Korea to deliver at least two new nuclear power units in the country, with an option for an additional four units. This will bolster the country’s existing nuclear fleet of six reactors that today generate about one-third of Czech electricity. Poland aims to begin construction of its first nuclear power plant in 2026.

France intends to construct at least six new reactors, partly to replace some of its ageing plants. In a notable shift, in 2023 the French government rescinded its objective from 2014 to reduce the share of nuclear energy to 50 percent by 2025. Such U-turns are uncommon with renewable energy.

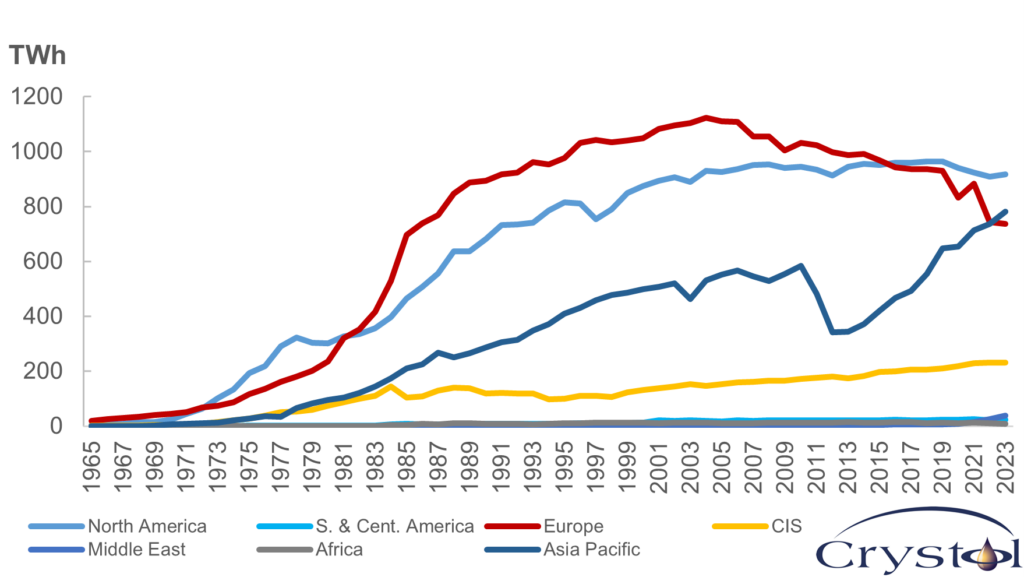

Nuclear power generation by region

Source: Energy Institute (2024)

In the Middle East, countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia are looking to join the United Arab Emirates and Iran as nuclear energy producers, primarily to free up more hydrocarbons for exports while addressing rapidly growing domestic energy demand.

Yet conversely, in North America, no new reactors are currently under construction. The U.S. government is focusing on extending the operational life of existing reactors, which typically receive a 40-year license that can be extended for two additional 20-year periods, for a total lifespan of 80 years.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) asserts that lifetime extension of existing nuclear power plants is highly competitive and remains the cheapest option for low-carbon generation compared to building entirely new power plants, either nuclear or conventional. Extending the use of nuclear plants is an indispensable and cost-effective strategy on the path to net zero by 2050, the agency argues.

Climbing construction costs

Nuclear power plants, once operational, are capable of providing a competitive, predictable and stable supply of electricity at scale without emissions. However, they require substantial upfront capital investment and have lengthy construction times, with a medial duration approaching eight years, compared to two and four years for gas- and coal-fired power plants, respectively.

The World Nuclear Association has pointed to economic risks stemming from competition with subsidized intermittent renewable energy. It says that government support for renewables is a major issue today, as the variability and intermittent nature of power generation from renewable energy forces other more stable generating sources, such as nuclear, natural gas or coal, to adjust their output at short notice, impacting profitability.

Moreover, nuclear projects typically face cost overruns and construction delays. Hinkley Point C, the United Kingdom’s first nuclear power plant in two decades, has been under construction since 2016. Its completion date has been pushed back several times, with the current estimate now set for 2029, leading to rising costs that far exceed those in initial projections that estimated completion “well before 2020.”

The highly specialized knowledge required for safe nuclear plant operation, decommissioning and disposal of waste contributes to rigorous regulation. The industry in fact is the most heavily regulated energy sector, which in turn can cause delays in construction and cost increases, limiting rapid expansion.

Despite stringent safety standards and oversight, the shadows of past disasters – most notably Three Mile Island in the U.S. in 1979, Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union in 1986 and Fukushima in Japan in 2011 – loom large, significantly shaping public perceptions of nuclear energy.

These disasters have had lingering impacts; after Chernobyl, Italians in a 1987 referendum voted overwhelmingly against further nuclear development, and the country gave up using domestically produced nuclear power. Similarly, on June 30, 2011, three months after the Fukushima disaster, Germany’s parliament voted to phase out nuclear energy altogether – an objective fully achieved in April 2023. Germany’s use of fossil fuels has increased as a result.

In December 2023, Spain followed suit, announcing plans to completely phase out its nuclear power by mid-2030, starting gradually in 2027, as it aims for a 100 percent renewable electricity system by 2050. Spain, along with Austria, the Netherlands and Denmark, strongly opposed the EU’s inclusion of nuclear power in its sustainable investment taxonomy.

Nuclear power politics

The IEA argues that advanced economies – where nuclear investments have stagnated and both budgets and timelines of the latest projects have frequently ballooned – have lost momentum and market leadership. Between 2017 and 2022, only four of the 31 new reactors then under construction were not of Russian or Chinese design.

At the forefront of the nuclear market is Russia, the world’s largest exporter of nuclear reactors and a leading supplier of enriched uranium. Its flagbearer is Rosatom, the State Atomic Energy Corporation, which maintains a dominant position globally with a reactor-construction order portfolio comprising 39 power units in 10 countries. Rosatom is also unique in possessing the full spectrum of technologies associated with the nuclear fuel cycle, from uranium mining to the decommissioning of nuclear facilities.

However, the economic and political repercussions of the war in Ukraine pose a considerable threat to Russia’s continued preeminence in this sector, with broader implications for the expansion of nuclear power globally. While Rosatom itself is not subject to Western sanctions, some of its subsidiaries are. In May 2024, the Biden administration enacted a ban on imported Russian enriched uranium – although waivers can be issued under specific circumstances. Russia had been America’s top foreign source of the fuel, supplying about a quarter of the uranium used in U.S. reactors, and earning about $1 billion a year from those sales alone.

In Turkey, the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant – the country’s first, developed in collaboration with Russia and with completion originally slated for 2028 – has announced delays. Rosatom’s director general, Alexey Likhachev, blamed the setbacks on “the Americans, who are going between our legal entities, between our banks.” Similarly, in Egypt, Rosatom’s $30 billion El Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant has encountered logistical problems, with its initial completion date of 2022 long since passed.

Scenarios

Unlikely: Global net-zero targets to be reached by 2050 supported by nuclear

To achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, global nuclear power capacity must more than double, according to the IEA. However, given historical trends, ongoing opposition to nuclear power, the retirement of ageing reactors and the intensifying competition from alternative energy sources – particularly renewables – this ambitious target seems increasingly unattainable.

Possible longer term: Smaller nuclear units gain acceptance

Proponents of nuclear energy argue that advances in technology, especially the development of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), hold the promise of enhanced safety, efficiency and waste management. Additionally, nuclear fusion presents the potential for a virtually limitless and clean energy source. However, SMRs remain largely conceptual, and nuclear fusion is still at the experimental stage. The economic viability and competitiveness of these technologies will only be tested when they are deployed on a broad scale. Currently, reliable data on their commercial viability is scarce, making it hard to forecast their potential contributions accurately.

Most likely: Nuclear power expansion to lag behind

The most likely scenario is that nuclear power will continue to lag behind other sources of energy for the foreseeable future.

Facts & Figures

Nuclear numbers

- In August 2024, China approved a record number (11) of permits for new nuclear reactors.

- Between 2013-2023, nuclear was one of the slowest growing energy segments, with a growth rate of just 0.5% per annum during this period.

- Since 2012, the Asia-Pacific region has emerged as the fastest-growing market for nuclear power, boasting an average growth rate of 8.5% from 2013-2023.

- In 2022, the Asia-Pacific region surpassed Europe in nuclear energy production.

- Although nuclear power is used in 32 countries, the market remains highly concentrated: The U.S., China and France account for 58% of global nuclear generation, and the top ten countries for 84%.

- Two-thirds of the world’s uranium production comes from Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia.

Related Analysis

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

“The potential of small nuclear reactors“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2022

Related Comments

“Will the gas crisis in Europe act in favour of nuclear energy?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2022