Dr Carole Nakhle

At a time when climate change appears to have lost its pole position in the global debate, a major development took place. After nearly a decade of negotiations on how to tackle emissions from the shipping industry, on April 11, 2025, the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization (IMO) member states – which represent the majority of the global fleet – voted to impose a levy on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions effective from 2028.

The deal sets two tiers of emissions-intensity reduction targets for the industry: a lower target of 4 percent in 2028, rising to 30 percent in 2035; and a more ambitious target of 17 and 43 percent in 2028 and 2035, respectively. Ships that do not meet the targets must pay a levy of $100 and/or $380 per metric ton of emissions, depending on what has been achieved and what has been missed.

The agreement, which is to be finalized in October this year, has received mixed reactions. Some countries wanted to see stronger measures, while others, primarily oil-rich nations led by Saudi Arabia, criticized the deal. The United States withdrew its participation, threatening “reciprocal measures” to offset any fees charged to American ships.

Irrespective of whether the targets were lenient or tough, the IMO succeeded in setting the first global industry-wide pricing mechanism for GHG emissions. Many have described the agreement as the first global tax on climate pollutants – a highly controversial and contentious issue where politicians and experts do not see eye to eye.

Economists largely agree that carbon pricing, whether through taxes or an emissions trading scheme (ETS), is an effective and efficient way to reduce GHG emissions and address climate change. Politicians, however, see it as an unpopular mechanism that can cost them dearly at the ballot box.

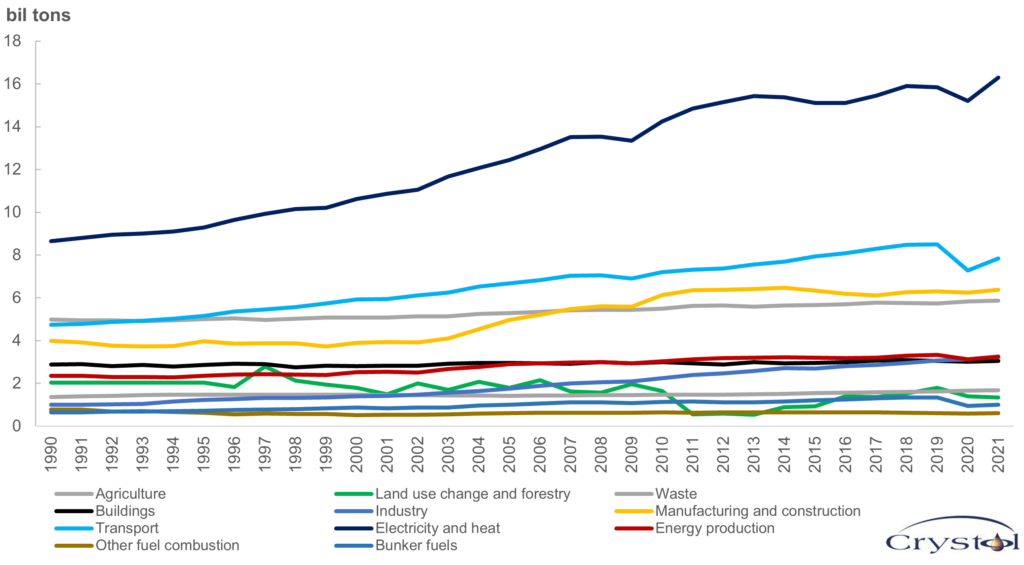

Global CO2 emissions by sector

Source: Climate Watch (2024) Our World in Data

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney provides a good illustration of the rift. Prior to entering politics, Mr. Carney, an economist and a former banker who also acted as the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, argued in favor of pricing carbon, stating during an interview at COP26 in 2021 that a global carbon price would be the best option to fight climate change. Yet, on his first day as prime minister on March 14, 2025, just before calling elections, he cut the federal consumer carbon tax to zero. This prompted several provinces – including British Columbia, the original pioneer of the tax in Canada, in 2008 – to follow suit.

The policy was presented as an essential step to reduce the burden on consumers and protect Canadian industries, especially following U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff threats. Climate policies like carbon taxes are often seen as threats to domestic competitiveness, which means they are often subject to sudden and drastic reversals.

To fight climate change while shielding domestic industry from cheaper but less energy-efficient imports from countries with lax climate regulations, the European Union introduced a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which levies a tax on the carbon content of imports, effective from 2026. The tax is supposed to ensure that imported goods pay the same carbon price as domestically produced goods within the EU.

However, the measure has been described as a “carbon tariff” and “green protectionism” by many countries, including China and India – the EU’s third- and eighth-largest trading partners. CBAM also raised concerns about compliance with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, particularly regarding fair and nondiscriminatory treatment of imports. The EU subsequently announced changes to the application of the tax, relaxing some of its rules and exempting smaller businesses from the tax.

Putting a price on carbon will continue to divide opinions, especially when there is no international agreement on the measure. Many countries still do not have any carbon pricing mechanism in place nor the institutional capacity and market maturity to do so. While the IMO’s recent resolution suggests that the world is moving closer to achieving a global pricing mechanism for carbon, the road ahead is still long and fraught with difficulty. This is especially true today, as the world economy fragments and trade wars intensify.

The rationale behind carbon pricing

Economists argue that a price signal is a powerful tool to influence behavior. Since GHG emissions – of which carbon dioxide accounts for more than 75 percent – are the main culprit behind climate change, putting a price on carbon ought to be one of the most effective climate mitigation policies.

Because the global energy system is the largest source of CO2 emissions, putting a price on carbon raises the cost of carbon-intensive fuels – coal, oil and natural gas – and activities, discouraging their use and helping to reduce emissions. A study published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that relying solely on spending measures to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 could increase public debt by up to 50 percent of gross domestic product. However, countries could decrease this debt burden significantly (10-15 percent) and generate revenues by implementing carbon pricing policies. The additional revenues could be used to lower other taxes, or fund green investments.

Carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETS) are both market-based mechanisms to price carbon. The former is a tax on the carbon content of fuel supply, thereby encouraging producers to minimize their carbon footprint, otherwise they incur an additional cost. If they can transfer some of that additional cost to their customers, the price of the service or goods they provide will increase accordingly, incentivizing customers to look for alternatives.

A tax of $35 a ton on CO2 emissions, for instance, would increase prices for coal, electricity and gasoline by about 100, 25 and 10 percent, respectively, one study found.

ETS require firms to obtain allowances for their emissions or carbon content, with the government setting the supply and the market determining the price through trading. In other words, a carbon tax provides price certainty that investors typically value, then lets the market determine the level of emissions under the resulting price levels. ETS, meanwhile, set the “volume” of carbon emissions by fixing the number of permits to be traded, then let the market determine the price (hence providing more certainty over the level of emissions).

Differences between carbon taxes and emissions trading systems

The two market-based carbon pricing mechanisms come with advantages and disadvantages. On balance, carbon taxes have significant practical advantages over ETS, especially for developing countries. They generally fall under the purview of the ministry of finance and are therefore easier to integrate into the existing tax scheme, whereas ETS are typically administered by environmental ministries. In 2019, more than 3,354 economists, including 28 Nobel Laureates and four former chairs of the U.S. Federal Reserve, signed an open letter supporting the introduction of a carbon tax, arguing:

A carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary. By correcting a well-known market failure, a carbon tax will send a powerful price signal that harnesses the invisible hand of the marketplace to steer economic actors towards a low-carbon future.

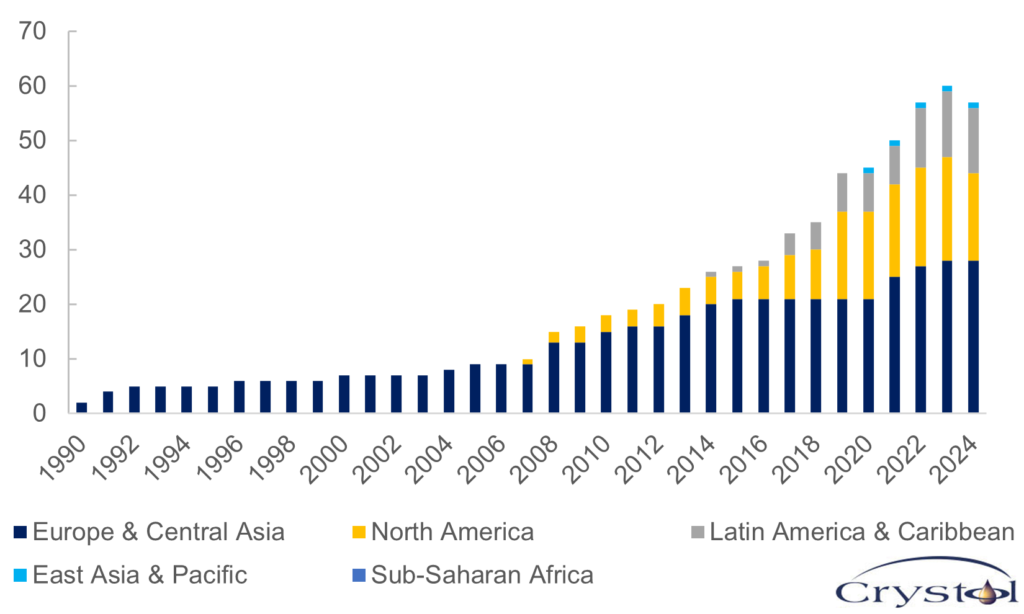

In practice, carbon taxes and ETS are not mutually exclusive and several countries, particularly in Europe, use both. The continent has been the leader in the development and application of the two measures, with Finland being the first country to introduce a carbon tax in 1990. Fifteen years later, the EU launched the world’s first international ETS. The two practices have since spread across continents; however, much variation remains in prices and coverage – that is, the share of GHG emissions subject to pricing. In Argentina, the carbon tax is set at $5 per ton of CO2 equivalent, compared to $127 in Uruguay, but in the former, the tax covers 20 percent of nationwide GHG emissions, nearly double that of its neighbor. The EU ETS has resulted in a price of more than $61 per ton, whereas in China the price is only $13. The resulting world average price is around $20 per ton of CO2 equivalent, covering nearly 25 percent of global GHG emissions.

Number of carbon taxes and emissions trading systems around the world

Source: The World Bank

The World Bank dashboard provides an excellent overview of different schemes adopted around the world. However, the bank warns that prices are not directly comparable due to differences in coverage, compliance and compensation arrangements. Also, since some countries apply both schemes simultaneously, headline carbon tax rates tend to be lower where an ETS is in place.

Overlooked benefits of carbon pricing

Not all governments share Europe’s enthusiasm when it comes to carbon pricing. Oil- and gas-producing countries tend to reject the idea, believing that such a measure would endanger their most important industry with significant negative spillovers on their economy. Eleven out of the 16 countries that voted against the IMO’s emissions levy are members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), with Saudi Arabia nearly derailing the agreement by calling for a last-minute vote – an unusual move for UN bodies that usually agree on measures by consensus.

While those concerns are understandable, carbon pricing may offer oil and gas producers more benefits than commonly recognized.

Norway, Western Europe’s largest oil and gas producer, is a good example. The Scandinavian nation was among the first countries – and was the first major non-OPEC oil and gas producer – to introduce a carbon tax on its petroleum industry in 1991. The tax is among the highest in the world and its rate has been raised regularly. Additionally, the industry is subject to the EU ETS, which Norway joined in 2008.

Norway’s stringent carbon pricing policy made CO2 capture at the Sleipner and Snohvit carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects commercially viable. These are the only two large-scale CCUS projects currently operating in Europe. By capturing CO2, operators can avoid paying the carbon tax, making the investment worthwhile. Furthermore, the Norwegian oil and gas industry has one of the world’s lowest carbon-emissions intensity (the amount of CO2 equivalent emissions per unit of energy produced of oil and gas). Such a feature will likely serve Norwegian industry well in a climate-conscious world.

Additionally, a “carbon tariff” such as the EU’s CBAM would result in the transfer of some of the economic rent that could ensue from oil and gas sales from the exporting nation to the importer. However, if the exporter is already subject to, say, a carbon tax domestically, then it can claim a credit for the carbon prices already paid in its country of origin, and subsequently it can reduce or even eliminate the payment of additional taxes on the carbon content at the border. This would also safeguard the home country’s fiscal revenue base.

Support from the industry

Given the additional fiscal burden imposed on high emitters, one would expect carbon taxes to be unpopular among industries like fossil fuels. In reality, however, the oil and gas industry has been supportive of a carbon price. One study found that out of the 50 largest oil and gas companies analyzed, 78 percent support carbon taxes.

In 2021, the American Petroleum Institute (API), which includes almost all the leading oil and gas companies operating in the U.S., published a Climate Action Framework where it endorsed a national carbon price that would help in maintaining adequate energy supplies in a lower-carbon future. From the industry’s perspective, such a price would accelerate technology and innovation like CCUS and hydrogen. It can also mitigate emissions from operations, including reducing or eliminating gas flaring and methane emissions. A carbon price would be more effective and transparent than a patchwork of regulations and mandates, the API argues.

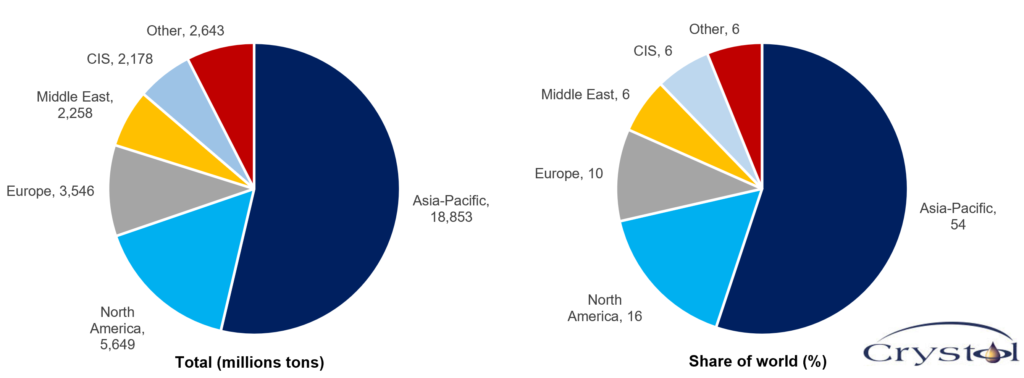

CO2 emissions from energy by region, 2023

Source: Energy Institute

But there are more strategic drivers behind the support. On the one hand, a carbon price would reduce competition from coal, which in turn would support the natural gas business. On the other, oil and gas companies believe that the ideal formula for a carbon price is unlikely to be developed and implemented anytime soon, for two main reasons.

First, while oil and gas production, transport and processing activities account for nearly 15 percent of global energy sector GHG emissions, the remainder comes from consumption, primarily in power, industry, vehicles, heating, shipping and aviation. Carbon pricing is an “economy wide” measure that would, according to the API, “price carbon at the outset for all relevant GHG emissions across the economy, from all relevant sectors and all emitters, accounting accurately for the benefits, costs and amounts of GHG emissions.” In this scenario, the brunt of the cost will be borne by consumers, whose energy bills are likely to rise notably.

Interestingly, in 2004, British oil major BP launched a public relations campaign called “what is your carbon footprint?” and a carbon footprint calculator. The campaign, which is credited for popularizing the term “carbon footprint,” intended to show consumers that their individual actions like going to work, buying food and traveling are important contributors to global warming, thereby indirectly telling them that they too are to blame.

Second, the industry has been calling for a global price on carbon – one that creates a level playing field. In 2015, ahead of the Paris Climate meeting, six major oil companies, namely BG Group (later acquired by Shell), BP, Eni, Shell, Statoil (later renamed Equinor) and Total (today known as TotalEnergies) sent an open letter to governments and the UN saying that they can take faster climate action if governments provide strong carbon pricing and link it all up into a global system. “Whatever we do to implement carbon pricing ourselves will not be sufficient or commercially sustainable unless national governments introduce carbon pricing even-handedly and eventually enable global linkage between national systems,” the letter states.

A cynic would argue that companies know how difficult it is for governments to agree on a global price for carbon. One study concluded in 2023: “The current division among the international community could leave oil and gas companies several more decades to exploit their remaining reserves before a policy response limiting their production is effectively put in place.” Two years later, this division has worsened.

Scenarios

Likely: Calls for a global carbon price will increase following the IMO deal

Progress will continue at a snail’s pace, further hampered by the growing trade disputes. Governments will continue to pursue unilateral actions. However, such policies are far from enough to tackle a global problem. Individual countries will be concerned about the commitment of other countries and the potential impact of their unilateral decisions on the international competitiveness of their domestic industry. Meanwhile, the oil and gas sector will continue to face differing investment landscapes, as it has always done, but it will not abandon its plans to reduce the climate impact of its activities, hoping to gain a competitive advantage that would sustain them in a greener world.

Unlikely: Encouraged by the IMO deal, other industries will follow suit

Countries the world over, and including major oil and gas producers, agree on a global price for carbon that would offer a level playing field for all companies. Investment in green energy accelerates and climate targets are met with a much lower fiscal burden than previously feared. Under this scenario, achieving the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius, is within reach.

Related Analysis

“The UK attempts to become a ‘clean energy superpower’”, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2024

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

Related Comments

“Experts warn of trade tensions on oil demand“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2025

“Why London is a great place for energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2025