Dr Carole Nakhle

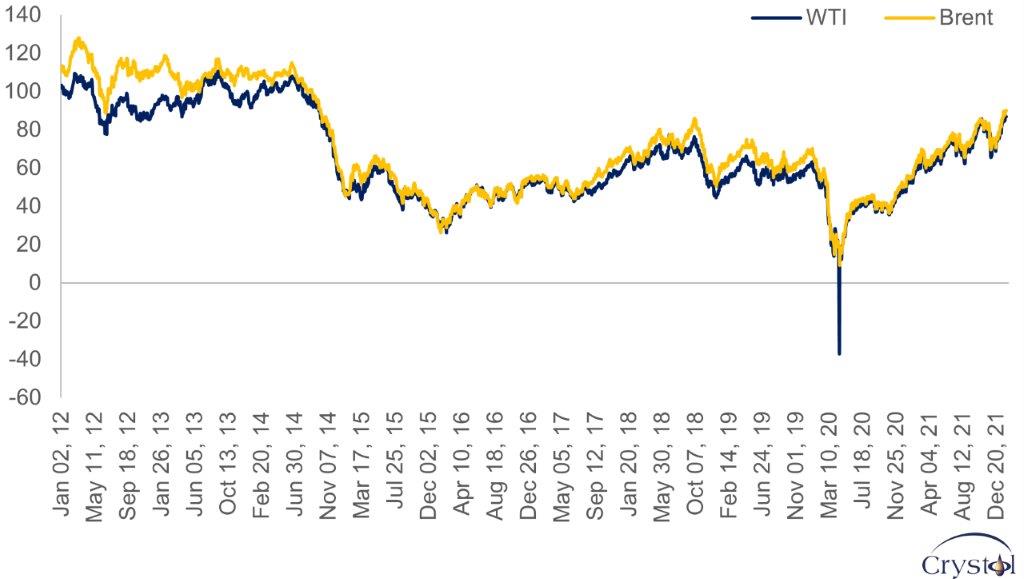

Oil markets started the year on a strong note after slowing down toward the end of last year. In December 2021, Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) averaged $74 and $71 per barrel. Then prices rebounded strongly in January and reached levels last seen in early October 2014. By the end of the month, Brent exceeded $91 per barrel and WTI $87 per barrel. The consensus, particularly among investment banks, is that prices will break the triple-digit mark. Goldman Sachs, for instance, expects prices to hit $100 per barrel later this year and continue rising in 2023.

A combination of dynamics is behind the change in gear – some are native to oil markets while other external forces are also having significant repercussions on market sentiment. Initial fears over the potential impact of the Omicron variant of Covid-19 on the transport sector, and therefore oil demand, soon dissipated. As evidence emerged that the variant is milder, at least compared to its Delta predecessor, forecasts were revised upward.

Daily Crude Oil Spot Prices, $ per barrel

Data Source: EIA, 2022

Meanwhile, geopolitical tensions between world powers are escalating rapidly. The situation is particularly tense between the United States and Russia, the largest and third-largest oil producers in the world respectively. Many fear serious disruptions to oil supplies, particularly now that the prevailing perception is that the market is tight and demand outpaces supply. No wonder prices have climbed.

However, the outlook for the rest of the year will not necessarily be defined by these concerns, especially if the geopolitical risk subsides.

Tight market

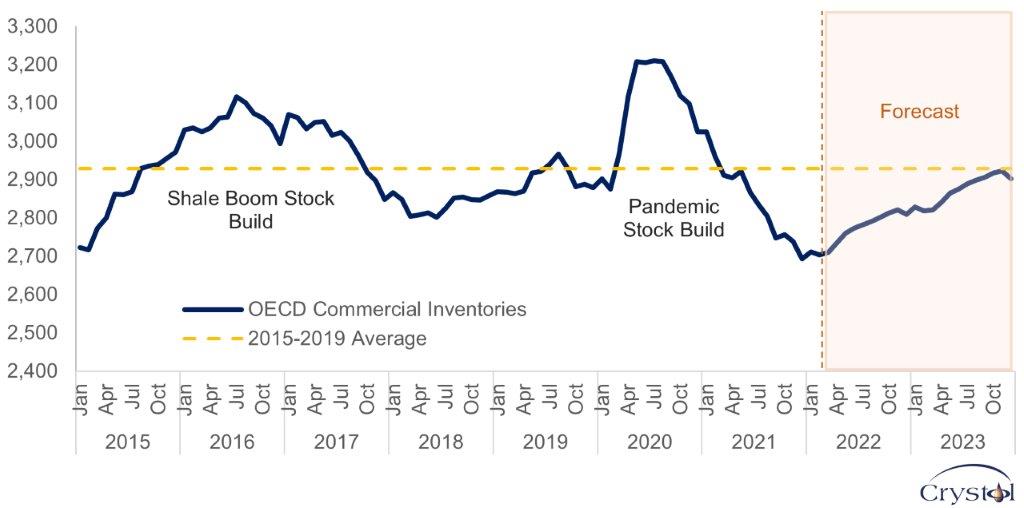

To determine the state of the market and the balance between supply and demand, analysts typically focus on the level of commercial oil inventories or stockpiles. In simple terms, inventories building up means supply exceeds demand while a decline indicates demand outpaces supply.

When the pandemic started and governments introduced lockdowns the world over, oil demand took a massive hit. Inventories became bloated. By introducing historic production cuts, the OPEC+ countries attempted to drain the record buildup in inventories and bring them in line with or below their pre-pandemic five-year average (2015-2019).

Data now confirms that by adopting a gradual but limited increase in production, the producers’ group achieved its goal. In December 2021, commercial oil inventories in developed economies hit their lowest levels since January 2015, as global oil demand continues to grow, and supply remains constrained.

OECD Commercial Oil Inventories, million barrels

Data Source: EIA, 2022

Judging by the inventories metric alone, one can clearly see that the oil market is tight. When the “safety cushion” is so thin, potential disruptions to the supply can cause prices to spike. In such circumstances, the impact of geopolitics becomes more pronounced, especially when major oil producers are involved or/and when there could be repercussions on oil supplies (for example, sanctions targeting Russian energy exports). Experts often refer to these threats as a “geopolitical risk premium” added to the price, even though in reality this premium cannot be precisely quantified.

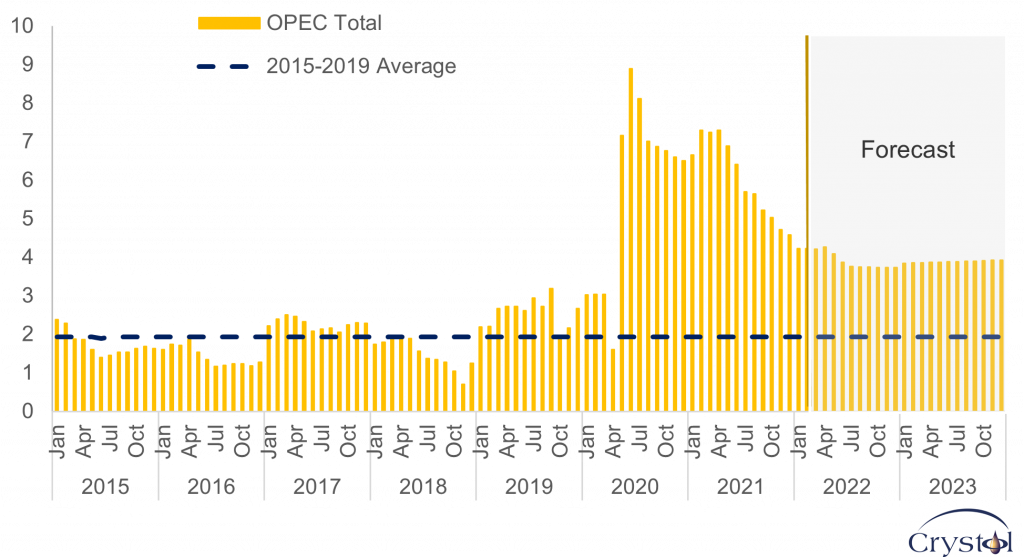

As inventories dwindle, market observers have turned their attention to another safety cushion: OPEC spare capacity. But there is little comfort to be found there at the moment.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) defines spare capacity as the volume of production that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days. The EIA adds that the extent to which OPEC utilizes its available production capacity is often used as an indicator of the degree to which the group is exerting upward influence on prices. Private companies in oil markets rarely hold spare capacity, or not voluntarily, because it is too costly to do so. Governments do and require the same from state companies, but these are strategic reserves meant for emergencies, not a tool to influence markets. OPEC spare capacity provides an additional indicator of the global oil market’s ability to respond to potential crises. As a result, oil prices tend to incorporate a higher risk premium when it is running low.

Looking at recent data, one can clearly see that OPEC spare capacity has been eroding since the substantial buildup of summer 2020. Back then, it reached 9 percent of world oil supply; today it stands at 4 percent.

Other factors influencing oil prices

The market is tight now, but the question is whether prices will continue to relentlessly march upward. It is a possibility, especially if the conflict over Ukraine is not resolved soon. However, leaving the geopolitical wild card aside, the same data that is making most analysts nervous today could become less worrisome as the year progresses.

First, with respect to commercial oil inventories, according to the EIA, a rapid buildup is expected starting in spring. Furthermore, the figures available are those of the OECD; the accumulation of inventories in other parts of the world, like in China and India, is not publicly known and whatever is reported is simply guesswork.

OPEC Spare Capacity, million barrels per day

Data Source: EIA, 2022

Second, it is true that high oil prices are typically observed when demand is rising fast, and OPEC spare capacity is running low. The only exception in the last 20 years was 2014 when both prices and spare capacity were low. Back then, OPEC was engaged in its first price war with American shale oil. It had decided to open all taps and produce at full capacity to eliminate the newly emerging competition from shale, only to give up after 2016.

To understand the situation today, it is worth looking back at the first eight years of the 2000s. Oil prices were on a relatively long upward trajectory as demand was rising fast, causing OPEC spare capacity to evaporate to less than 1 percent of global supply. That relentless increase in demand was driven by the growth and industrialization of China and other emerging markets. This was not a recovery following a previous crisis, but rather genuine economic growth, which continued until the global crisis of 2008-2009 dampened it. The global market, other than using up OPEC’s spare capacity, had no way of providing more oil in response to this strong demand, so prices rose steadily until the crisis. Back then, many believed the world was running out of oil. But in the end, shale oil eventually increased supply as a response to higher prices.

Looking better

The question today is whether a similar situation is likely, with supplies shrinking and prices further increasing.

Various forecasting agencies expect additional supplies to come to the market later this year (and well into the next), with the U.S. leading growth outside OPEC. This explains why OPEC spare capacity is expected to stabilize from the middle of the year then increase in 2023.

The EIA forecasts oil production to outpace oil consumption in both 2022 and 2023, resulting in inventories buildup. This does not account for a possible deal with Iran, which would bring additional barrels to the market.

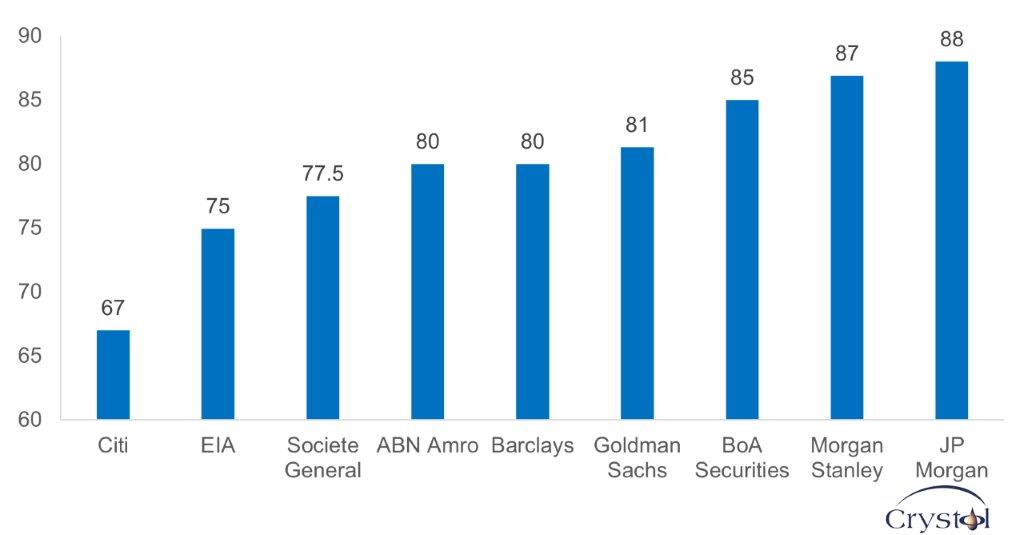

Oil Price Expectations for 2022, $ per barrel

Data Source: EIA, Argus, reuters

U.S. annual oil production is expected to rise to record levels in 2023 as shale producers continue to boost output, surpassing the annual high of 12.3 million barrels a day achieved in 2019 – once again, a straightforward response to higher prices.

Although oil demand is expected to keep increasing, the pace will be slower than what was recorded in 2021, especially as economic growth moderates. In its January 2022 World Economic Outlook, the IMF downgraded its growth forecasts for most major economies, compared to its October 2021 outlook. “The global economy enters 2022 in a weaker position than previously expected,” the organization stated, with high inflation playing a major role.

Looking at the oil price forecasts made by major agencies and investment banks for this year, one cannot help but notice that estimates differ by more than 30 percent between the most ambitious (JP Morgan) and most conservative (Citi). With a lot of moving parts in the economy-energy-geopolitics nexus, these analyses are partly guesswork.

Based on currently available data, it is difficult to share the sense of panic conveyed by many experts and echoed in mainstream media. But it still remains perilous to predict the exact timing of future developments.

Facts & Figures: Oil in 2022

- In January 2022, Goldman Sachs raised its Brent oil price forecasts from $81 to $96 for 2022 and from $85 to $105 for 2023.

- In December 2021, U.S. inflation hit its highest level in four decades (7%) while the eurozone saw its highest rate ever (5%).

- According to the international monetary fund, global growth is expected to moderate from 5.9% in 2021 to 4.4% in 2022 and 3.8% in 2023.

- The International Energy Agency raised its global demand estimates by 200,000 barrels per day for 2021 and 2022 due to softer Covid restrictions.

- The U.S. is both the world’s largest consumer and producer of oil.

Related analysis

“Oil markets: What crisis?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2021

Related Comments

“Why crude oil prices are rising“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2022

“Oil prices rise despite the possibility of China withdrawing from its SPR“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2022

“Major risks for energy markets in 2022“, Dr Carole Nakhke, Dec 2021