Dr Carole Nakhle

At a dinner at the German embassy in London on October 23, 1980, German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt shocked British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher when he told her that West Germany relied upon the Soviet Union for 14 percent of its daily natural gas consumption. “That was very dangerous and unwise,” she said. Mr. Schmidt responded, “My dear Margaret, the Russians have always been the most reliable suppliers. They need us as much as we need them. There is no danger at all.” For nearly 40 years, the chancellor’s optimistic assessment appeared accurate, and Germany’s dependence on Russian gas only kept increasing.

In 2021, for instance, more than half of Germany’s gas supply originated from Russia. Germany was Russia’s largest gas customer in the European Union, accounting for nearly 53 percent of its exports to the EU. These exports are primarily by pipeline. Two major pipelines, Nord Stream 1 (under the Baltic Sea to Germany) and Yamal (to Poland and Germany via Belarus) cross German territory. The more recent addition has been Nord Stream 2, a replica of Nord Stream 1 (both in terms of route and capacity).

Then came the war in Ukraine. Not only did the dynamics of gas markets change abruptly – particularly in Europe – but it also opened a new chapter in the German-Russian relationship, with significant repercussions on Germany’s energy policy.

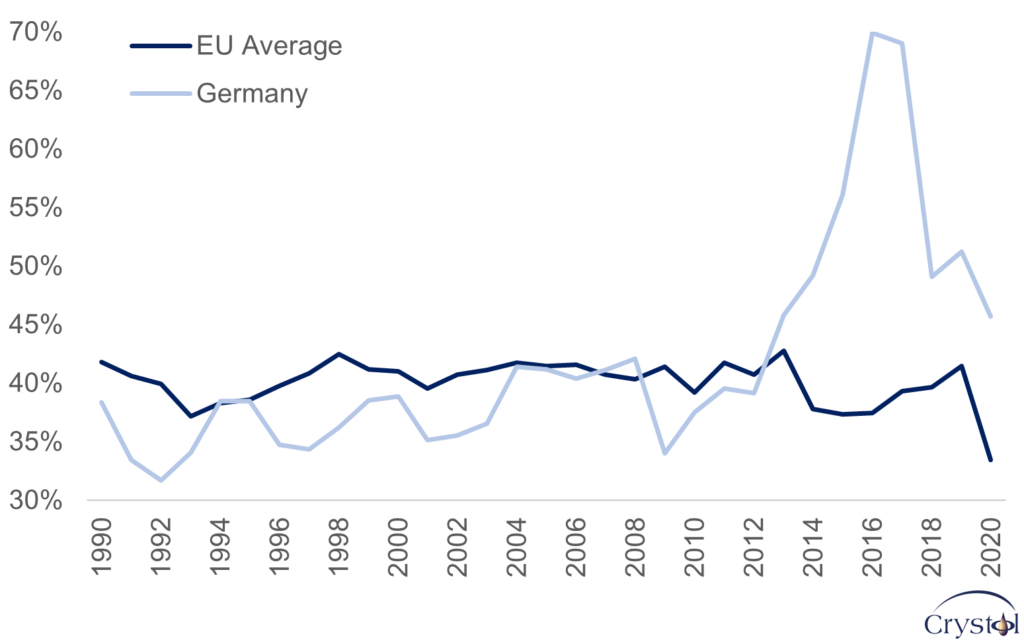

EU dependence on Russian gas

Data Source: IEA

The role of gas

Germany is the largest economy in the EU and the fourth largest globally, which is why its economic health is closely watched. It is also a significant player in energy markets. An export-driven and energy-intensive economy, it is the seventh-largest energy consumer, accounting for 2 percent of the world’s energy consumption (after China, the United States, India, Russia, Japan and Canada).

Compared to the world’s biggest economies, Germany has the most extensive penetration of renewable energy in its energy mix – 19 percent. However, fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – still dominate its primary energy mix, providing 76 percent of the country’s energy needs. Natural gas (26 percent) is the second-biggest contributor after oil (33 percent).

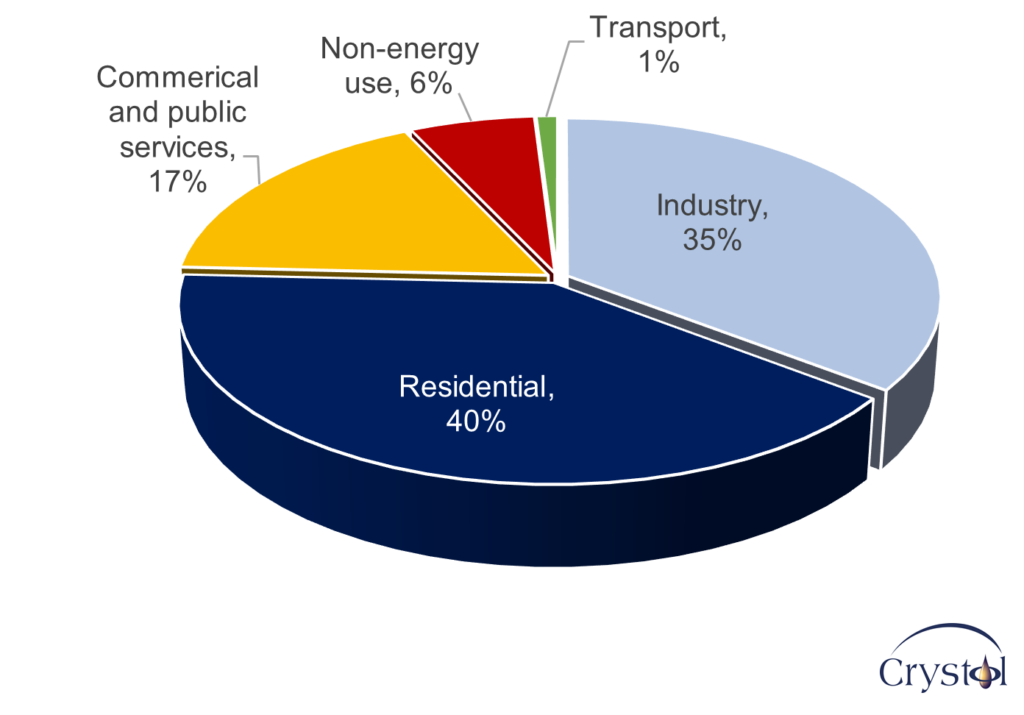

The main natural gas users in the country are residences (primarily for heating) and industry, where gas is used as a feedstock for industries such as chemicals. While in power generation, natural gas can be substituted with any other energy source, it is not easily replaceable in its role as an industrial feedstock.

Natural gas use by sector in Germany

Data Source: IEA

To source its gas, Germany heavily relies on imports. Domestic gas production accounts for a mere 5 percent of total consumption and is in decline. The rest of the gas is imported from Russia (55 percent of imports), Norway (31 percent), the Netherlands and reexports from neighboring EU countries.

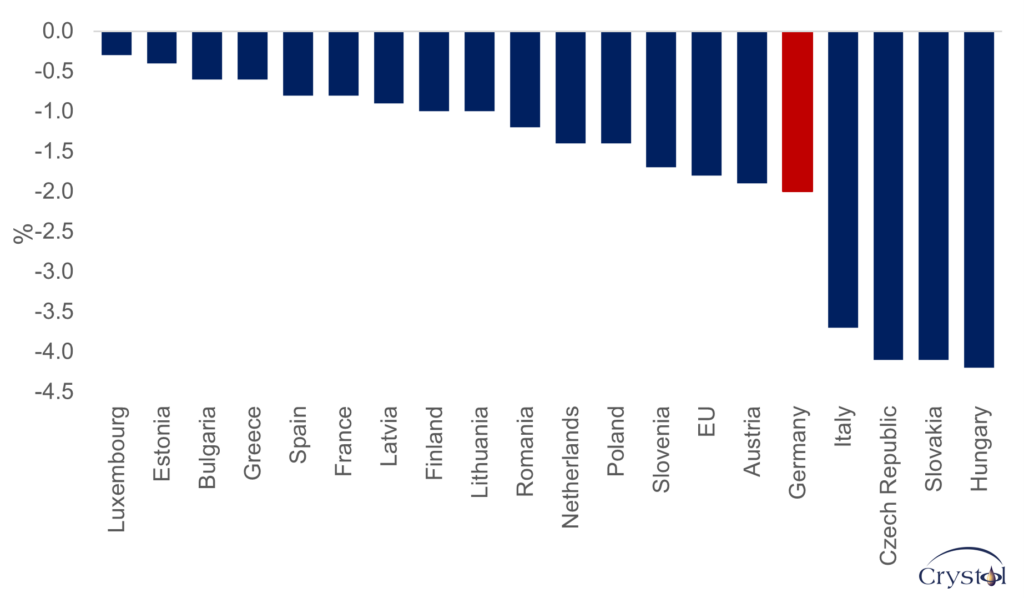

High economic cost

The loss of Russian gas supplies will therefore have a high economic cost. However, the impact depends on several factors, such as the volume of the disruption, its duration, the winter’s severity and government and public responses. Given the volumes imported from Russia, Germany will be one of the hardest-hit economies in the EU in the case of a complete Russian gas shutoff, according to the International Monetary Fund. On June 23, 2022, Germany moved to the second level of its three-stage emergency gas plan, the first European country to take such action.

Potential loss in GDP due to shortages in Russian gas supplies

Data Source: IMF

Special relationship no more

For decades, German leaders dismissed warnings about the country’s energy exposure, but the war in Ukraine, which coincided with new leadership in Germany, became the watermark in the German-Russian relationship. In November 2021, as trouble was brewing in Ukraine, Germany suspended the certification of the completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, citing some regulatory gaps that the operator still needed to complete. In reality, Germany bowed to the mounting pressure from the U.S., the United Kingdom and Ukraine due to their concerns about Russia’s potential military actions in Ukraine.

When Russia’s intentions became evident in February 2022, Germany went one step further and halted the pipeline, an act described by Ukraine as providing “moral leadership.” With such a dramatic decision, Germany used Russia’s favorite nonmilitary weapon to put pressure on its leading gas supplier.

Russia retaliated by gradually reducing gas flows through its operating pipelines, but interestingly, that did not happen immediately. In fact, Russia cut its supplies to other European countries, with Poland, Bulgaria, the Netherlands and Finland being hit first. Moscow tried to safeguard its biggest customer in Europe, and Berlin was initially reluctant to impose any sanctions on Russian energy imports, describing them as “a red line” in March.

Then in April, Germany’s stance started to harden again. Berlin supported the sanctions on coal and, in May, the EU sanctions on oil. The measures were limited to seaborne imports, but Germany went further and announced it would ban all oil imports from Russia by the end of 2022. It also declared it would replace Russian gas imports by mid-2024, as Russia had become an “unreliable supplier,” according to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. The chancellor explained that Moscow had been a reliable energy partner “even during the Cold War,” but the rule no longer applied.

From the Russian perspective, why wait for 2024 and lose all leverage if the German market was shutting down anyway? By cutting gas supplies sooner, as Russia has been gradually doing since the summer, Russian President Vladimir Putin was trying to achieve two objectives. The first is maximiSing gas export revenues by putting upward pressure on prices. The second objective is to increase the likelihood of public discontent and anti-government protests in Western Europe by tightening supplies ahead of winter, which is the high season for gas demand. If prices increased further, movements like the Yellow Vests in France in 2019 could push Berlin (and other European capitals) to change their stance on sanctions and the war in Ukraine.

Countermeasures

Germany has announced several measures to minimize the impact of a complete loss of Russian gas supplies. Some included a more aggressive stance on previously set targets, such as those related to renewable energy. In April 2022, the German Cabinet published a draft legislative package called the Easter Package and described it as the “biggest energy policy reform in decades.” Instead of its previous goal of reaching a 65 percent share of renewable energy in Germany’s power generation by 2030, the Easter Package set that share to at least 80 percent with the aim of “almost” 100 percent by 2035.

Other measures have revived previously discussed but forgotten projects such as liquefied natural gas (LNG). Germany does not have a port facility to import LNG. Now the government plans to invest in two permanent land-based import terminals while leasing five floating units (called FSRU) to be deployed starting from the end of this year. Germany is trying to secure long-term purchases of LNG from Canada, Qatar and the U.S.

The government has also reversed previously announced decisions. It passed a law to reactivate coal and oil-fired power plants as a temporary measure; only in 2021, Germany intended to accelerate the coal phaseout in power generation. Similarly, the government decided to postpone closing the three remaining nuclear power plants, initially scheduled for the end of 2022.

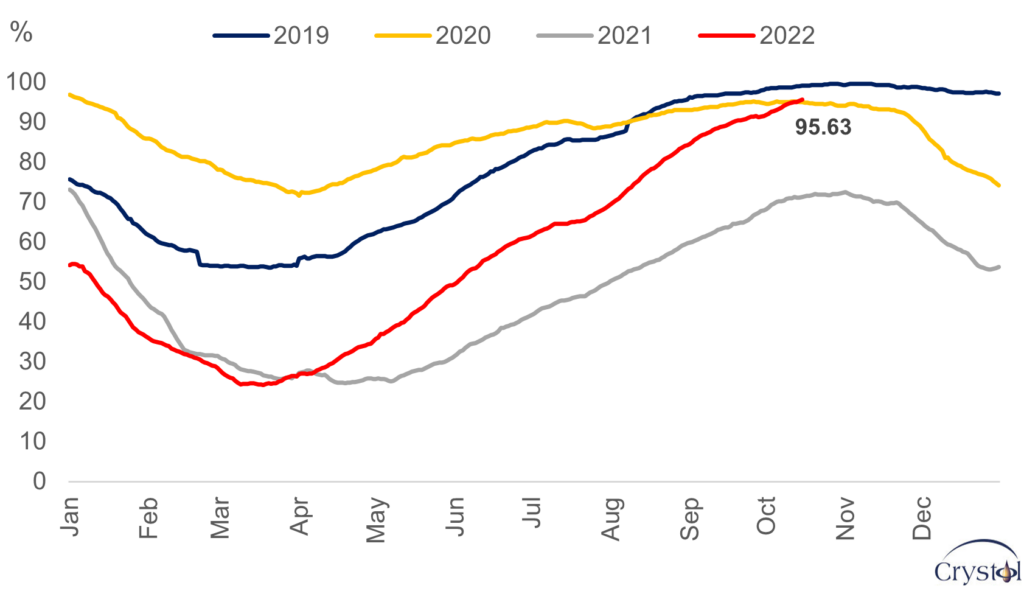

Germany has also accelerated the filling of gas storage to achieve 95 percent in November – a much healthier level than last year.

The government has asked citizens and companies to reduce gas consumption by at least 20 percent to avoid emergency cuts. The suggested measures include purchasing electrical heaters and installing wood stoves.

German gas storage levels

Scenarios

While the above measures will help alleviate the pain of a complete cutoff of Russian gas in the coming winter, Germany has a steep challenge ahead. For instance, even 100 percent-full inventories would be exhausted after only about 10 weeks, while winter usually lasts between 12 and 18 weeks. Besides, no one can predict how cold winter will be.

The five planned FSRUs can secure around 25 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas per year, but this is less than half the capacity of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. Renewable energy will help, but its impact in the short term will be limited. And in the longer term, backup fossil-fuel-firing power plants will be needed to compensate for the variable electricity generated from green energy sources. As for LNG, while it will surely give Germany more options, it will expose it to greater competition for supplies – and higher prices in an already tight market.

Breaking away from a relationship that endured over decades is not going to be easy, especially when that relationship has been with a giant low-cost supplier. Several of the measures that Germany is pursuing today should have been adopted much earlier, irrespective of the level of trust between Germany and Russia. The leaks at Nord Stream 1 and 2 which have technically disabled the flow of gas through those pipelines, and which may seem to have been caused by deliberate detonations, have only strengthened the argument. After all, the fundamental pillar of energy security is diversity and diversity alone.

Facts & Figures

- Germany’s energy consumption has been declining over the last two decades.

- In its electricity mix, renewable energy has the biggest share (37.2%), followed by coal (27.8%), gas (15.2%) and nuclear (11.8%), with minor contributions from other sources of energy.

- On average, Germany’s energy import dependency is higher than the EU’s.

- In September 2010, the Federal Government of Germany adopted its first official environmental targets for 2050. “Energiewende” became the nickname for the country’s long-term strategy to transition to a sustainable green energy system.

- The government has agreed to a 15 billion-euro bailout for Uniper, Germany’s largest importer of Russian gas, to ensure it can continue to operate and fulfill its contracts.

Related Analysis

“Thatcher’s energy plan was derailed – now we are paying a gigantic price“, Lord Howell, Sep 2022

“Energy policy confusion“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2022

Related Comments

“How did Europe arrive to the current energy crisis?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2022

“European gas crunch, African supply and the energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Sep 2022