Dr Carole Nakhle

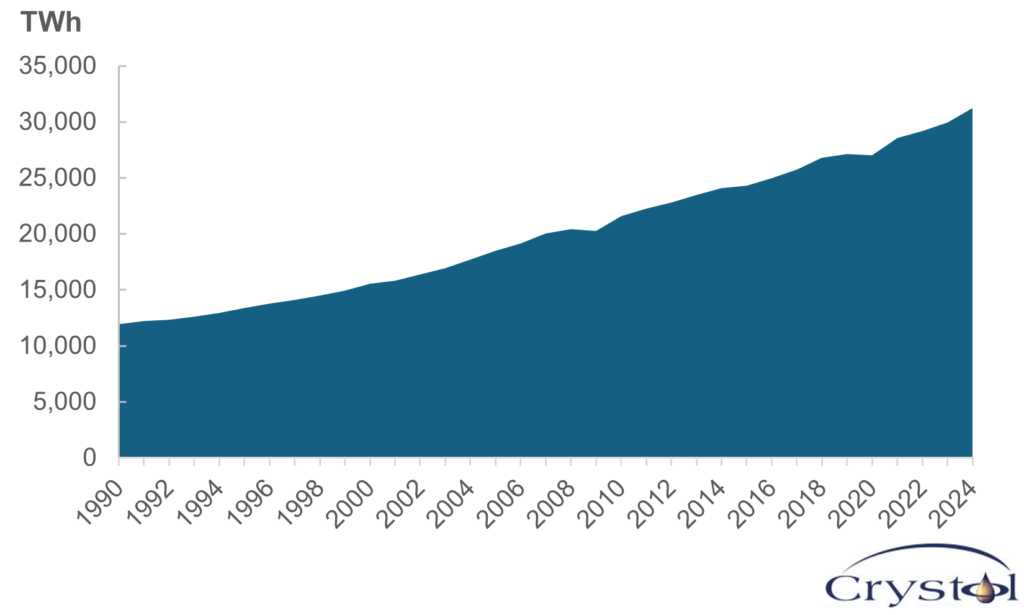

Electricity has long been one of the greatest enablers of human progress, transforming societies and powering economic development for more than a century. Today, its importance is only intensifying. Worldwide, total electricity generation has nearly tripled over the last three decades, with demand surging across almost every sector. The latest significant rise is fueled by the electrification of transport, heating and cooling, alongside the rapid expansion of digital infrastructure, including data centers and artificial intelligence-driven services as well as cryptocurrency mining.

Global electricity generation

Source: Our World in Data

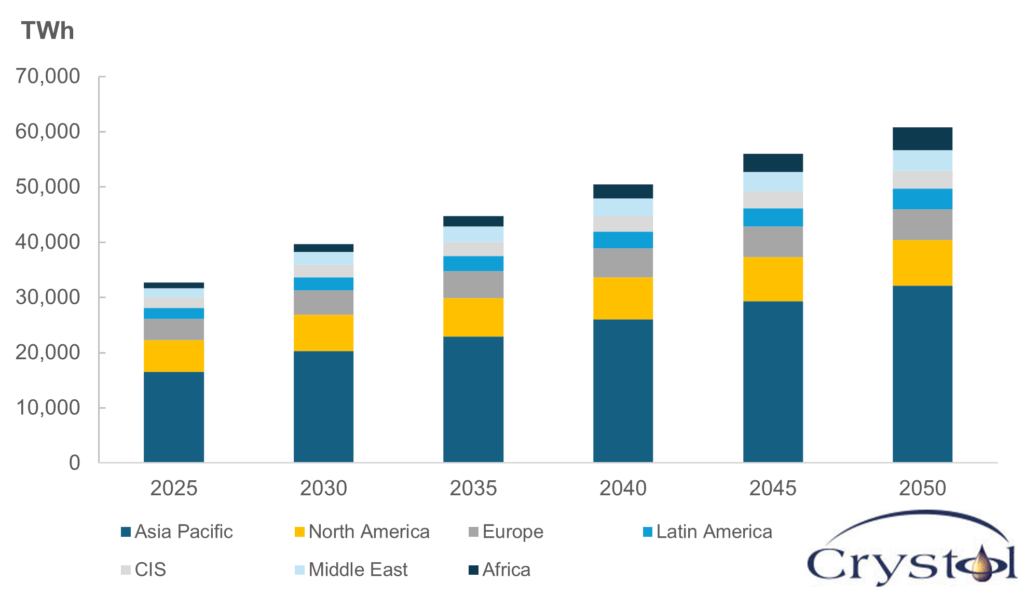

The Middle East, in particular, is witnessing dramatic growth in electricity demand. Since the beginning of the century, the region has recorded the second-highest increase in electricity demand (70 percent) after Asia-Pacific (73 percent) and it is growing at a rate 10 times faster than Europe (7 percent). Much of the growth is concentrated in high-intensity sectors, including industrial development, cooling necessitated by extreme heat and desalination to address water scarcity.

The momentum is expected to continue: By 2030, the Middle East is expected to overtake Latin America to become the fourth-most electricity-consuming region in the world (after Asia-Pacific, North America and Europe). In addition to the traditional growth factors, the proliferation of data centers and AI infrastructure in the Gulf’s oil- and gas-rich states has emerged as a major driver of demand, adding a new layer of stress to already complex power systems.

The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, for instance, are pursuing ambitious AI strategies that could place unprecedented demands on their electricity systems. The UAE wants AI to contribute 20 percent of its non-oil gross domestic product by 2031, with flagship projects like the Abu Dhabi Stargate data-center campus potentially reaching 5 gigawatts (GW) of capacity – a load comparable to large industrial zones or small cities. In Saudi Arabia, the sovereign AI company Humain plans to deploy 1.9 GW of AI-specific compute capacity by 2030, scaling to 6.6 GW by 2034. The company aims to capture around 7 percent of the world’s AI workloads.

These GW-scale data-center ambitions, while essential to positioning the Gulf as a global AI hub, will generate electricity demand comparable to that of medium-sized urban areas and will place significant pressure on existing power infrastructure. This further highlights the urgent need to plan for grid capacity, flexibility and reliability to support this rapid expansion.

A dependable, robust and adaptable power supply underpins economic competitiveness, industrial growth and national resilience, particularly in the Middle East. As the region expands electricity generation to meet growing domestic demand and support energy-intensive ambitions, key questions arise: Where will the electricity come from, how will it be generated and what will this mean for the region’s economic competitiveness and carbon footprint? The answers to these questions will shape not only national energy strategies but also the Middle East’s role in the global energy landscape.

Electricity demand outlook by region (in TWh)

Source: Enerdata

The peculiarities of electricity in the Middle East

When it comes to the power sector, the Middle East stands out for its unusually narrow fuel mix. Oil and gas account for around 92 percent of its electricity generation – the highest level of fuel dependence anywhere in the world. The only region that comes close is Asia-Pacific, where fossil fuels make up about 71 percent of power generation, mainly from coal and natural gas. The Middle East’s reliance on oil and gas spans both hydrocarbon-rich and hydrocarbon-poor countries, making it a rare common feature in an otherwise highly diverse area.

Globally, many countries phased out oil from power generation after the first oil crisis in 1973. In contrast, oil has remained a structural component of electricity generation in many Middle Eastern states. While the continued use of oil is understandable, given the abundance, accessibility and low cost of local resources, this reliance carries significant environmental and economic implications.

Environmentally, although oil emits less carbon than coal, it remains far more carbon-intensive than natural gas, renewables or nuclear power. Economically, the consequences are more acute for hydrocarbon exporters. Every barrel burned at home is a barrel not sold abroad. Saudi Arabia offers a striking example. On peak summer days, the country can burn an additional 1 million barrels of oil per day for power. At an oil price of $60 per barrel, that translates into a daily loss of $60 million in export revenue, effectively sacrificed to keep air conditioning running.

Without a serious effort to diversify the power mix, this diversion of export potential toward domestic consumption will only intensify as electricity demand continues to rise. For resource-poor countries in the region, the burden takes a different shape: They must bear the cost of importing increasingly expensive fuels simply to keep the lights on.

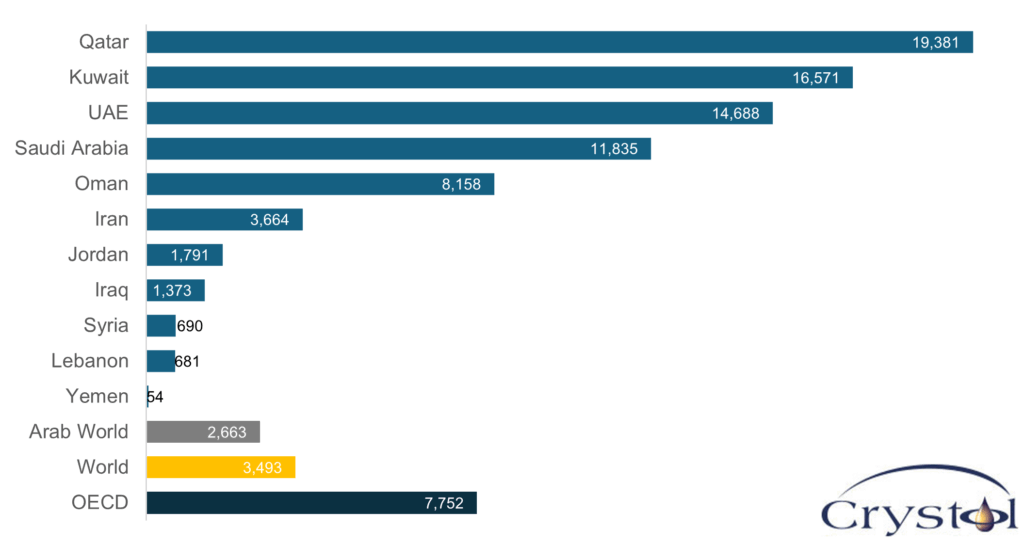

Electric power consumption (kWh per capita)

Source: World Bank

Another factor that sets the Middle East apart is the deep heterogeneity of electricity access and consumption. The region is often viewed as a single energy entity; in reality, countries such as Kuwait, the UAE and Saudi Arabia rank among the world’s highest consumers per capita, owing to energy-intensive industries, extreme cooling needs and high standards of living. In contrast, nations like Lebanon, Syria and Yemen have some of the lowest levels of electricity consumption worldwide, reflecting limited access, unreliable infrastructure and prolonged economic and political crises. These wide disparities in per capita electricity consumption mean that while some countries face high demand pressures and economic trade-offs, others struggle with limited access and infrastructure challenges.

Power Security

The Middle East faces a growing electricity security challenge due to rising demand and its unique climatic conditions. In a region characterized by intense heat and water scarcity, reliable power infrastructure is vital for sustaining everyday life. But electricity security goes beyond basic power provision. It is central to fostering economic growth, supporting technological and social development, ensuring national security and enabling an ambitious energy transition.

Abundant domestic oil and gas do not automatically guarantee secure electricity. Iraq provides a stark example. Despite being the second-largest oil producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and holding the world’s fifth- and 11th-largest proven oil and gas reserves, respectively, the country has struggled for decades to provide reliable power. Years of conflict, mismanagement and underinvestment have left the national grid fragile, forcing households and businesses to rely heavily on costly and polluting private generators. While Iraq’s situation is extreme compared with other oil- and gas-rich Gulf countries, it reflects a reality shared by conflict-affected states, including Yemen, Syria and Lebanon.

Across the Middle East, electricity security challenges vary, but common themes emerge. Meeting growing demand requires coordinated action on multiple fronts. In a region where uninterrupted electricity is increasingly vital, strengthening infrastructure, mobilizing investment, improving market efficiency and addressing institutional and regulatory weaknesses to ensure power systems can reliably support economic and social development is more important than ever.

Affordability is a key pillar of electricity security, not only for consumers but also for governments, given the prevalence of subsidies in the Arab world. Ensuring that electricity supply is reliable, accessible and fiscally sustainable is therefore central to securing the region’s power systems.

Managing Demand

Not all demand growth in the Middle East’s electricity system is inevitable. While climate change, population growth and rising temperatures are powerful drivers, governments still have meaningful levers to moderate the speed and scale of electricity consumption.

First, enhancing energy efficiency can play a major role in moderating electricity demand. For instance, air conditioning – a primary driver of peak load in the region – is often much less efficient than comparable units elsewhere. Upgrading to more efficient cooling technologies, together with improving insulation and building standards, could cut projected peak demand growth by tens of gigawatts over the next decade.

Pricing and subsidies are another effective tool. Electricity in many Middle Eastern countries is sold below cost. While these subsidies provide a social safety net and support industry, they are expensive for governments, encourage overconsumption and can exacerbate environmental impacts. Some states have implemented reforms, though fully removing subsidies remains politically and socially sensitive.

Supply Side Considerations

On the supply side, several Middle Eastern countries continue to add fossil fuel-based capacity, but much of the region’s existing power infrastructure is aging. Saudi Arabia illustrates the scale of this challenge: Roughly a fifth of its oil-fired units and more than a tenth of its gas-fired units have been in operation for over four decades. As more plants reach the end of their technical lives, governments will increasingly need to decide whether to prolong the operation of old assets through upgrades or shift toward newer, more efficient and lower-emission alternatives. These choices will shape not only the reliability of future electricity supply but also the pace and direction of the Middle East’s broader energy transition.

Diversification efforts are underway, but progress varies widely. The UAE stands out for its successful and rapid rollout of nuclear power, which now supplies around 20 percent of its electricity. Other countries have expressed interest in nuclear options, and small modular reactors may eventually offer a more flexible pathway, though concrete plans remain limited for now.

Renewables are also gaining ground, making the Middle East – the world’s largest oil- and gas-producing hub – one of the fastest-growing markets for new renewable capacity outside China. But the scale of deployment remains modest, with the region accounting for less than 1 percent of global renewable capacity today. Even this momentum is largely limited to the wealthier Gulf states. The UAE and Saudi Arabia are driving most of the new solar capacity and competitive renewable tenders, supported by strong balance sheets.

However, these countries’ ability to invest at scale is closely tied to revenues from oil and gas exports, highlighting a broader regional dilemma. Expanding clean power is essential for reducing the domestic use of hydrocarbons, yet the financial means to do so are themselves derived from those same resources. Meanwhile, countries outside the Gulf Cooperation Council often face tighter budgets and weaker institutions, making it more difficult to keep pace even as the pressures on their electricity systems intensify.

Ambitious targets reflect both the aspiration and the challenge. Oman, for example, aims for renewables to reach around 30 percent of its electricity generation by 2030 under Vision 2040. But today, roughly 98 percent of its power still comes from gas, with a small share from oil. Moving from such a concentrated fuel base to a diversified one in a short period will require accelerated project delivery, sustained investment and strong institutional coordination, illustrating the scale of effort required across the Arab world.

Scenarios

Likely: Gradual modernization

Middle Eastern countries gradually improve electricity security through efficiency measures, subsidy reforms and selective investment, but fossil fuels remain dominant. Wealthier Gulf states manage to enhance supply reliability and diversify their electricity generation mix incrementally, while conflict-affected and lower-income countries continue to face underinvestment and blackouts. Renewables and nuclear grow, but their share of the system remains limited.

As a result, electricity security improves moderately, fiscal pressures are managed but remain significant and regional disparities persist.

Less likely: Accelerated transition

Governments implement a rapid shift toward low-carbon and modernized electricity systems, combining strong efficiency improvements, subsidy reform and large-scale investment in renewables and nuclear. Even countries with weaker fiscal or institutional capacity make significant progress in reliability, while hydrocarbon revenues are partially redirected to finance the transition.

In this scenario, electricity supply becomes cleaner, more resilient and more affordable over time. Fiscal pressures are reduced and regional disparities in power access are substantially narrowed, positioning the Middle East’s energy sector as more stable and competitive.

Related Analysis

“U.S. shale oil and gas: From independence to dominance“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2024

“The UK attempts to become a ‘clean energy superpower’”, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2024

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

Related Comments

“Industry urges more nuclear power to cut balancing costs, but risk premium seen“, Christof Rühl, Oct 2025