Dr Carole Nakhle

The United States Energy Information Administration (EIA), the statistical and analytical agency within the Department of Energy, projects that the country will set a new oil production record this year, averaging 13.6 million barrels a day (mbd). Output is expected to exceed 13.7 mbd next year, affirming U.S. President Donald Trump’s claim at the 2024 Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: “We will do it at levels that nobody’s ever seen before.”

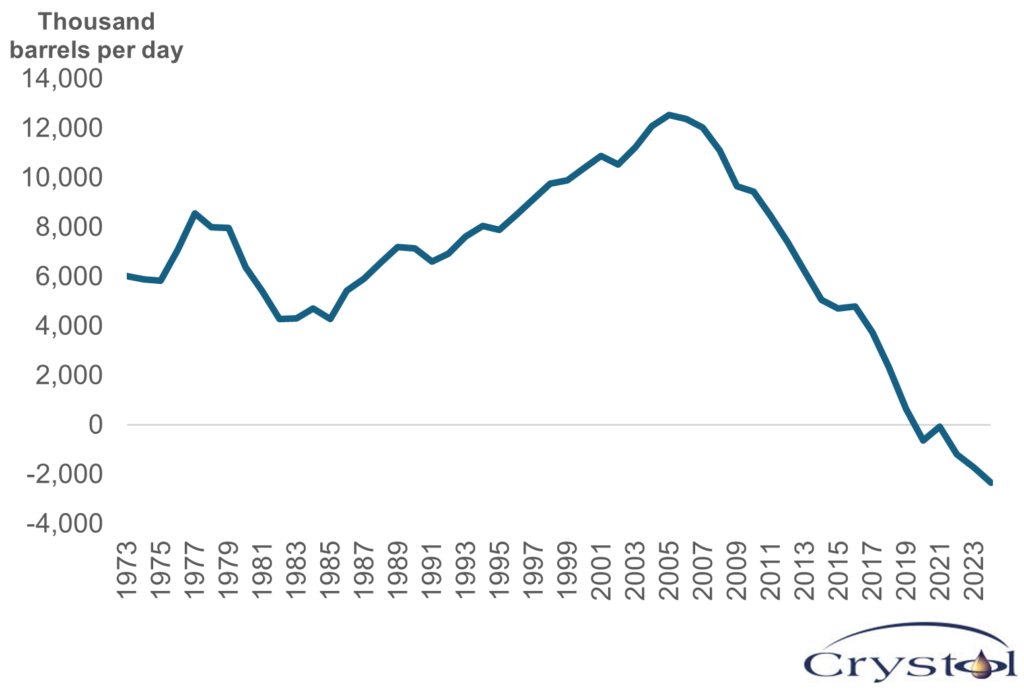

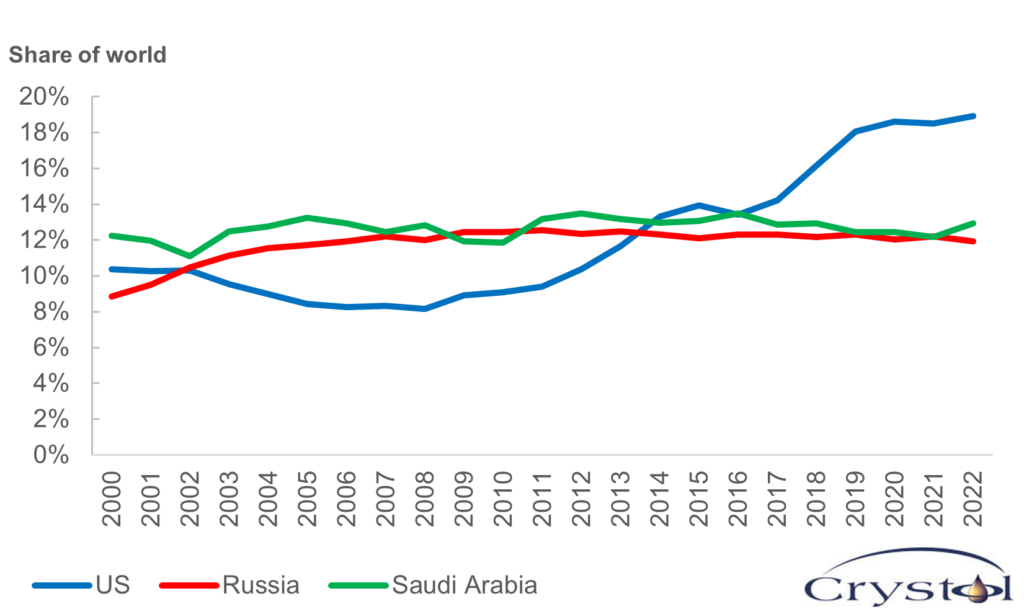

This is a significant shift in growth for a country that, for over 70 years, was a major importer of oil. In 2005, at the peak of U.S. oil imports, 40 percent came from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Since 2014 (except in 2016), the U.S. has been the largest oil producer in the world, driven by the shale revolution that began in 2008. This boom unlocked vast resources that were previously considered uneconomical. The rapid growth in domestic output not only allowed the U.S. to drastically reduce its oil imports but also to become a net exporter of oil, changing the dynamics of global oil markets and challenging established players in their traditional markets.

U.S. total net imports of crude oil and petroleum products

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

While spikes in oil prices have happened since, they have been short-lived, even when caused by ongoing major geopolitical developments affecting some of the largest oil producers in the world. During the first oil shock in 1973, when Arab OPEC members cut their supplies, prices surged and remained high for several years. Today, despite sanctions on key producers like Russia, Iran and Venezuela, Libya’s struggles to increase output, and ongoing military conflicts in the Middle East, among other issues, prices remain in the “low” territory. This has prompted many to question whether the market is underpricing the risks.

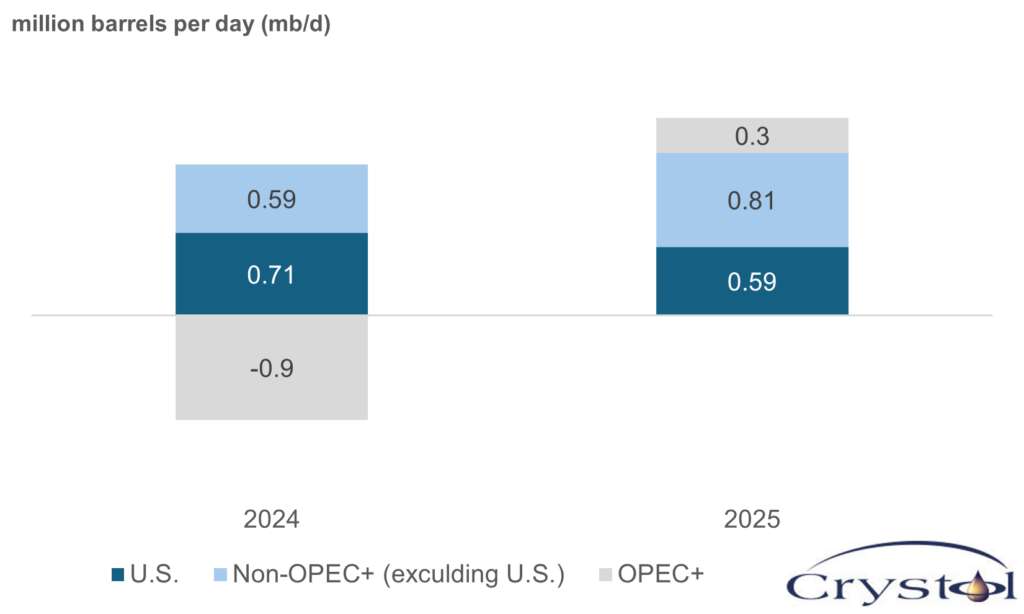

While multiple factors can explain the stubbornly low prices today, the availability of abundant and flexible supplies from the U.S. played a substantial role in calming nerves and addressing supply gaps when they occur. In recent years, the U.S. has led oil supply growth outside of OPEC+ (an alliance of OPEC members and non-OPEC oil-producing countries that cooperate on production levels), along with Norway, Brazil, Canada and Guyana, contributing to nearly 40 percent of total non-OPEC+ supply growth. Shale oil, or tight oil, accounts for more than two-thirds of total U.S. production.

Yet, the U.S. oil industry could see slower growth, potentially reversing many of the benefits gained during its ascent. According to the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook published on April 16, U.S. oil production may reach a peak as early as 2027. On the same day, the Department of Energy issued a statement, describing the scenario as “the disastrous path for American energy production under the Biden administration.” It added that the report does not “reflect policies enacted by President Trump to expand consumer choice and facilitate greater investment in American energy production.”

Forecasting of U.S. oil production, especially shale, has been inaccurate in the past, and there is a good chance it will be again. Even if the EIA’s projections hold, the consequences for global markets may not be as severe as many fear. Regardless of the most pessimistic EIA scenarios, the U.S. will remain a sizeable producer. More importantly, evaluating the U.S. in isolation from broader market dynamics can lead to simplistic conclusions. The overall outlook is different when oil demand is surging versus when its growth is dwindling.

Oil supply growth

Source: International Energy Agency (January 2025)

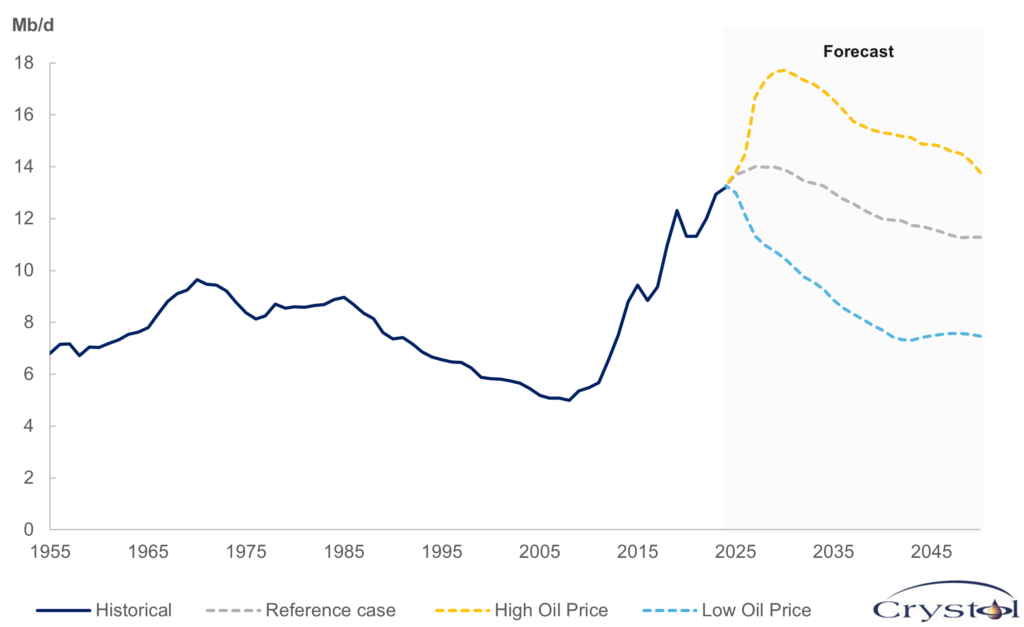

U.S. oil production outlook

The EIA predicts U.S. oil production will peak at 14 mbd in 2027. This level is projected to be maintained through the rest of the decade before starting to decline. This key finding has garnered international attention, supported by concerning statements from some shale producers. “We are at a tipping point for U.S. oil production,” stated Travis Stice, the chief executive officer of Diamondback Energy Inc., the largest independent oil producer in the Permian Basin in the U.S., in a letter to investors. He further noted that production has likely peaked in America’s prolific shale fields.

A decline in domestic production would affect both U.S. and global consumers. The most visible effect is an increase in U.S. net oil imports, which could restore its dependence on foreign supplies and intensify competition with other buyers. It would also reduce the global diversity of oil supplies, which has helped to keep prices relatively low and supported buyers in their pursuit of energy security. For instance, in 2024, the U.S. was the largest supplier of oil to Europe, reducing the continent’s reliance on the Russian energy market.

OPEC members are also positioned to benefit substantially from a reduction in American oil production. In 2014, the producers’ group made an unsuccessful attempt to “kill” shale oil by lifting all production restrictions in hopes that the resulting fall in prices would drive the higher-cost producers, primarily those in the U.S. shale oil sector, out of the market.

However, in more recent years, OPEC and its OPEC+ allies have kept production levels down to limit the decline in prices. During this time, they have seen the U.S. expanding its share in global oil markets primarily at their expense. Now, as major OPEC members pursue ambitious production expansion plans, weakened U.S. production will allow some members to regain lost market share and reclaim their dominance.

Top 3 global oil producers

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Overlooked factors driving American oil supply

Oil production, regardless of the location or field, is supposed to peak before eventually declining. However, pinpointing the date and level of that peak is not an exact science. Various factors such as unanticipated breakthroughs in technology, sustained market dynamics or drastic changes in government policies can influence the production trajectory of a project or an entire country. The shale revolution exemplifies this unpredictability, hence its description as a “revolution.”

In the early years of this century, the global debate was dominated by fears about an imminent peak in global oil supplies, which was blamed for a prolonged rise in oil prices. Few could have foreseen how the application of an established practice in the oil industry – horizontal drilling, with “hydraulic fracturing” (the process of creating fractures in rocks and rock formations by injecting specialized fluid into cracks to force them to open further) – would pave the way for a new supply into global markets.

Interestingly, the concept of peak oil supply traces its origins to the American geologist M. King Hubbert, who worked for oil major Shell. In 1956, he predicted that U.S. oil production would follow a bell-shaped curve and peak between 1965 and 1970. When production peaked in the early 1970s and subsequently declined, his model became the benchmark for understanding the production profiles of different countries. However, nearly four decades later, the shale revolution highlighted a fundamental flaw in Hubbert’s peak oil theory: It overlooks the power of technology.

Looking at the EIA’s scenarios, several aspects should also be considered. First, the EIA cautions that “energy models are simplified representations of energy production and consumption, laws and regulations, and producer and consumer behavior. Projections are highly dependent on the data, methodologies, model structures, and assumptions used in their development. These results are not predictions of what will happen.” It is therefore important to distinguish between forecasts and scenarios, which are subject to different assumptions and methodologies.

Second, a peak does not mean an end. The EIA’s own numbers indicate that even by 2050, the U.S. would still be producing around 11.3 mbd, maintaining its status as one of the world’s top producers.

Finally, the figures mentioned above represent only one scenario, a so-called reference scenario. But numerous factors can lead to different outcomes, such as high or low economic growth, costs for zero-carbon technologies, alternative electricity and transportation. The most impactful variable, however, is probably the price of oil.

U.S. oil production outlook

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The EIA considers three scenarios. In the reference case, crude oil prices start at $72 per barrel (b) in 2025 and rise to $91/b by 2050. In the low-price case, prices drop to $41/b in 2025 and then reach $48/b in 2050. And in the high-price case, they increase to $118/b in 2025 and $157/b by 2050 (all prices are in real 2024 U.S. dollars). Although each of these price scenarios yields different production outlooks, all three indicate a peak, albeit in different years.

Nevertheless, these scenarios offer limited insights if not taken within the broader context of global market dynamics: Reaching a peak when oil demand is booming is not the same as when demand growth is waning. There is greater consensus today that oil demand is approaching a peak. Irrespective of when that will be, the market is unlikely to witness the rapid growth rates that it once enjoyed, particularly given the global push toward a cleaner and greener energy mix.

Effect of oil prices on production

Investment in oil projects is influenced by the same variables, namely, oil price and market dynamics, cost, technology and government policies. However, there are two key differences between investment in shale oil and conventional oil. The first of these is the lead time between when the investment decision is made and when production begins. For a conventional project, this can easily exceed five years, with eight years being the average. In contrast, shale oil projects typically have a much shorter lead time, ranging between one year and 18 months. This leads to a second critical difference: the sensitivity to prices, or what economists term the price elasticity of supply.

Before the shale revolution, economic literature characterized oil supply as inelastic: Irrespective of current prices, production would remain unchanged for several years, as it is the result of investments undertaken years ago. The exception to this rule was the OPEC members, particularly those with spare capacity like Saudi Arabia. These countries earned the title of “swing producers,” enabling them to gain a significant influence over global oil markets.

The rise of shale in the U.S. has weakened OPEC’s influence. Unlike traditional producers, American private producers do not invest in building expensive spare capacity, as they operate at maximum capacity. They can swiftly adjust their investment plans and production levels based on the near-term outlook for oil prices. This adaptability is another reason the U.S. matters more to global oil market analysis (and to OPEC+ members), beyond the sheer volume it produces.

U.S. policies as a factor

The impact of policy must not be underestimated. For instance, by altering the tax system, host governments can improve an industry’s appeal to private capital. The U.S. Department of Energy stated that, “Under President Trump’s leadership … this administration is ensuring America’s future is marked by energy growth and abundance – not scarcity.” President Trump himself is committed to his well-known mantra, “Drill baby, drill.”

However, in the context of the oil sector, U.S. legislation stands out from what is commonly found elsewhere. In most countries, except in the U.S. (and some areas in Canada), the ownership of the natural resources underground belongs to the nation and is therefore subject to the fiscal system established by the governing authority.

In the U.S., this applies to areas under the sovereignty of federal authorities, such as the Gulf of Mexico. Shale production typically takes place on private land, where landowners have considerable say in devising contractual arrangements with investors. In this respect, what Washington mandates is likely to have a more muted direct effect on the shale industry, especially when compared to oil price.

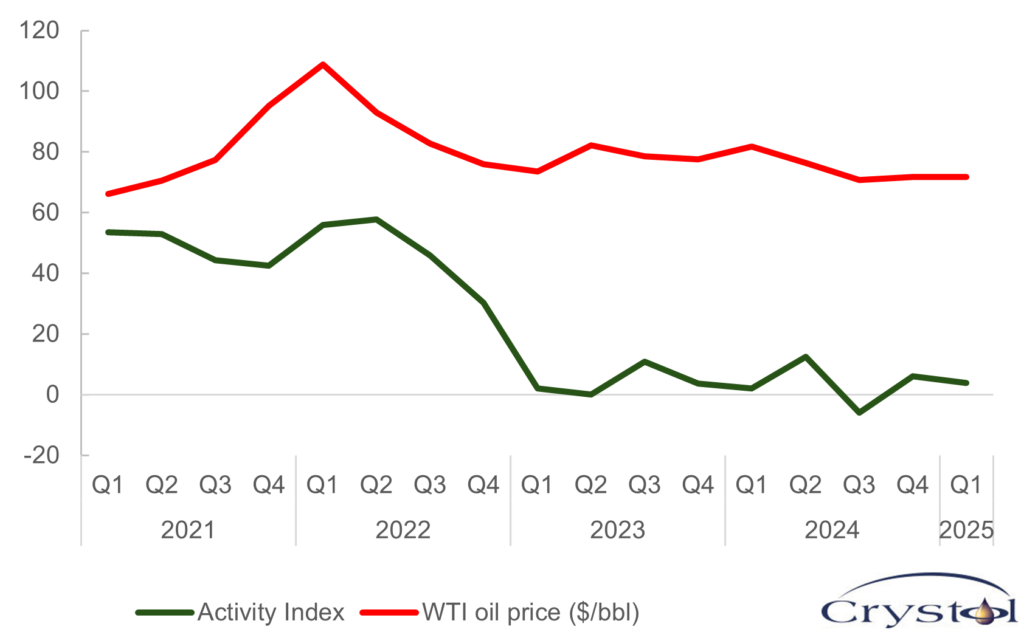

Activity index and oil price

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The Activity Index, published by the Dallas Fed Energy Survey and based on responses from industry participants, particularly in the shale business, demonstrates how the level of activity moves in tandem with prices, with a short time lag. When prices rise, they support greater industry spending, while price declines prompt activity to contract.

Scenarios

Likely: U.S. oil production will continue at high levels

The U.S. is one of the oldest oil producers in the world, significantly influencing the international oil trade. In a likely scenario, the country will sustain high production levels, although the pace of growth will react to prevailing market sentiments and crude prices. Even if production peaks in the next few years, the U.S. will remain a sizeable producer, continuing to challenge established producers, especially as oil demand’s growth falters.

America’s influence will also hinge on the ability of its domestic industry, particularly shale, to improve operational efficiency, making it more resilient to price drops should competition between international producers intensify. Although we can expect spikes in oil prices due to geopolitical developments, they are likely to revert to lower levels rather quickly.

Less likely: U.S. oil production growth is weakened

In a second, less likely scenario, an extended period of low oil prices significantly hinders the growth in U.S. oil production. Consequently, demand growth outpaces supply, thereby increasing the country’s dependence on imports. Many shale producers go out of business, much to the relief of OPEC+ members. While the latter will enjoy less competition, it will still have to confront the challenges posed by the realities of a shrinking market.

Related Analysis

“U.S. shale oil and gas: From independence to dominance“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2024

“The UK attempts to become a ‘clean energy superpower’”, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2024

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

Related Comments

“Experts warn of trade tensions on oil demand“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2025

“Why London is a great place for energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2025