Dr Carole Nakhle

On January 9, just a week after the United States military operation that led to the capture and removal of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, a group of oil executives met at the White House to explore potential investments in Venezuela’s oil sector. The gathering included a mix of U.S. and European energy majors, service providers, trading firms and smaller independent operators.

During the meeting, U.S. President Donald Trump urged these companies to commit at least $100 billion of their own capital to rebuild Venezuela’s aging infrastructure and restore production, which has fallen sharply over the decades. While the proposal was welcomed in principle, the realities of the country’s oil sector tempered optimism.

ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods offered a blunt assessment, telling the president that the current frameworks in Venezuela today make the country “uninvestable.” He stressed that “significant changes have to be made to those commercial frameworks, the legal system, there has to be durable investment protections, and there has to be a change to the hydrocarbon laws in the country.” Mr. Woods also noted Exxon’s past experience (the company has had its assets seized in Venezuela twice before) which underscores why uncertainty over legal protections and commercial arrangements remains a core concern for investors.

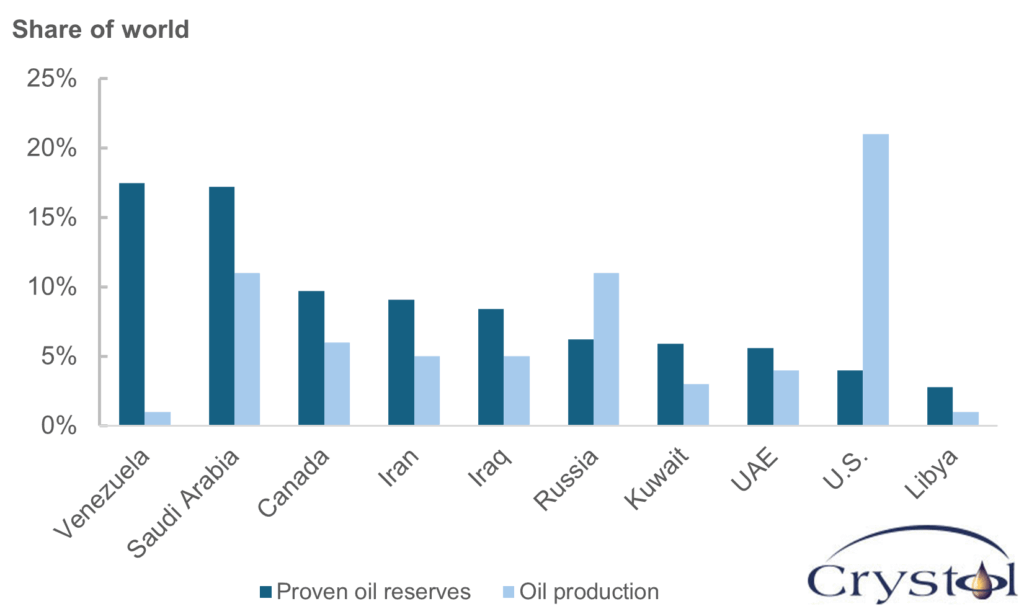

His observation highlights a fundamental principle in oil investment: Abundant resources alone do not guarantee that capital will flow. Investment decisions depend not only on geological potential, such as reserves and recoverable volumes, but also on prevailing market conditions and various above-ground factors in the host country. These include political and regulatory stability, fiscal terms, judicial quality, infrastructure and commercial frameworks. While companies can often overcome technical challenges in the subsurface, above-ground uncertainties remain crucial in determining investment success.

Investment capital flows to countries where governments create a credible, predictable and enforceable environment for long-term returns. Two jurisdictions may have similar geology, but differences in hydrocarbon laws, fiscal regimes, contract sanctity and policy consistency often determine where companies invest billions.

In Venezuela, decades of erratic policies, vague legal structures and resource nationalism have made investors cautious. Even with political signals from the U.S. and promises of support, the combination of policy, commercial and governance risks continues to make Venezuela a challenging environment for new investment.

Venezuela’s oil policy swings

In the mid-20th century, Venezuela leveraged its petroleum wealth to become a dominant global producer and a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), helping to redefine oil markets. However, over subsequent decades, a succession of policy shifts created an investment climate marked by uncertainty and volatility. What began as a strategic assertion of sovereignty evolved into an environment where frequent changes in ownership rules, fiscal and contractual frameworks, as well as governance priorities, eroded investor confidence. This helped cause a steep decline in production and a persistent reluctance among international companies to commit long-term capital.

In 1976, during President Carlos Andres Perez’s first term (1974-1979), Venezuela fully nationalized its oil industry with the creation of Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA). This process absorbed the operations of major international oil firms – including Exxon (then Standard Oil/Esso), Gulf, Mobil, Texaco and Shell – dismantling their concessionary control and converting their activities into state-owned subsidiaries.

Proven oil reserves and production, 2025

Source: The Energy Institute (2025)

By the late 1980s, Venezuela faced a critical challenge: PDVSA lacked the financial resources and technological expertise to fully exploit the country’s immense extra-heavy oil reserves. In response, Perez, during his second term (1989-1993), launched the apertura petrolera (oil opening), a partial reopening of the oil sector to private and foreign investment, through more attractive contractual arrangements and fiscal terms. Regulatory procedures were also streamlined to improve project viability and reduce bureaucratic hurdles. Production subsequently ramped up.

But the apertura was short-lived, reflecting Caracas’s broader pattern of swinging pendulum policies.

Hugo Chavez’s election victory in December 1998 marked a pivotal turning point for Venezuela’s oil sector. Politically, Chavez capitalized on widespread dissatisfaction with traditional parties, chronic inequality and the perception that previous governments had mismanaged the country’s wealth. His left-wing, populist agenda appealed strongly to a populace frustrated by social and economic stagnation, promising to redistribute oil revenues to social programs, empower marginalized communities and challenge entrenched elites.

Anti-foreign investment sentiment played a key role in this narrative. Foreign oil companies were often portrayed as profiting from Venezuela’s resources at the expense of the nation, making them convenient targets for nationalist rhetoric. This narrative mirrored the one that preceded the first wave of nationalization.

Chavez’s rise also coincided with an evolving international oil market. In the late 1990s, oil prices began recovering from the lows that had persisted throughout the decade, and by the early 2000s, prices surged on the back of growing global demand and fears of resource scarcity. This created a wider perception that oil was becoming increasingly valuable and that producing countries could assert more control over their reserves. Host governments worldwide began tightening fiscal terms, renegotiating contracts and asserting greater ownership, but Chavez implemented these measures more aggressively than most.

The convergence of domestic political appeal and favorable global oil market conditions empowered Chavez to pursue bold expropriations, higher taxes and restrictive contracts, while maintaining popular support at home. Contracts were rewritten to require PDVSA to hold a majority 60 percent stake in all projects. Companies faced a strict “take it or leave it” offer; some foreign companies reluctantly accepted the new terms, but others like ExxonMobil refused, and their assets were nationalized.

Under President Nicolas Maduro, policy uncertainty, weak governance and ambiguous hydrocarbon legislation continued.

Embedded resource nationalism

The political dynamics shaping Venezuela’s oil sector today cannot be fully understood without appreciating the historical resonance of resource nationalism the country’s political identity. Venezuela’s assertion of control over its oil resources long predates Hugo Chavez. Even after Nicolas Maduro’s removal in January, this ingrained nationalism continues to shape both domestic policy and investor perceptions.

The interim authorities have initiated reforms to liberalize aspects of the hydrocarbons sector, including reducing the fiscal burden and offering international arbitration mechanisms for disputes. On January 29, Venezuela’s National Assembly greenlit reforms of the Organic Law on Hydrocarbons, fundamentally reshaping the nation’s oil sector. This overhaul will provide foreign companies with greater operational leeway. On the surface, these changes represent a meaningful departure from the hardline resource nationalism of the Chavez and Maduro years.

However, many Venezuelans remain skeptical of foreign involvement, especially when it is perceived as openly infringing on their sovereignty to manage their own resources. Reforms have already sparked debate and led to proposed amendments, reflecting tensions within the political establishment about the pace and extent of opening up the sector.

To weaken opposition to reforms, Acting President Delcy Rodriguez has asserted that Venezuela “does not take orders from any external actor” and declared that the country has had “enough” of outside directives. This language reflects the enduring salience of resource nationalism in Venezuelan political discourse – a factor that continues to shape both domestic policy debates and international investor perceptions of legal and political risk.

Weak rule of law and corruption are blocking oil investment

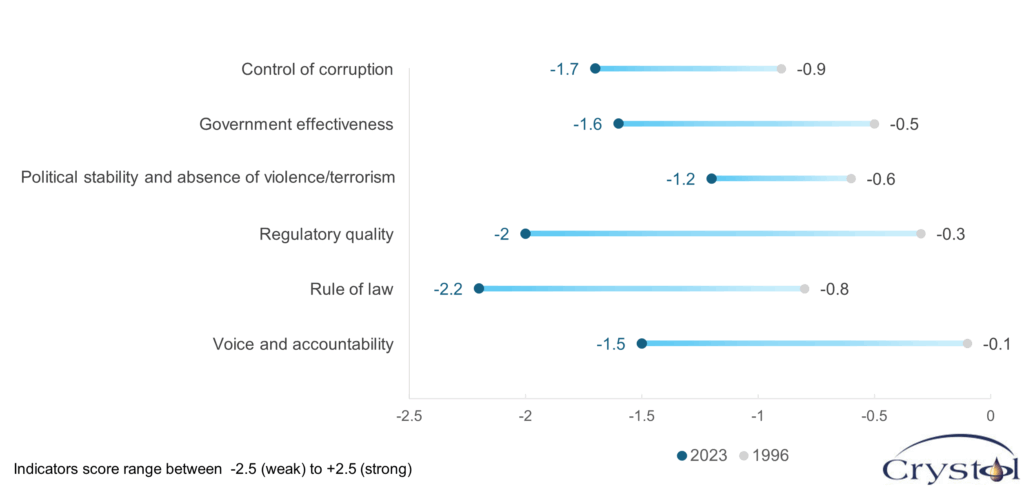

Venezuela’s oil investment climate is also deeply affected by its governance deficits. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators measure governance performance on a scale roughly from -2.5 (weak) to +2.5 (strong). Venezuela’s scores show a pronounced decline over the past decades. For example, its rule of law rating fell from about -0.8 in 1996 to -2.2 in 2023, while government effectiveness and regulatory quality have also deteriorated sharply, though they were never stellar to start with. Negative scores in political stability, control of corruption, as well as voice and accountability underscore ongoing institutional fragility, political instability and limited public participation.

Governance indicators: Venezuela

Source: The World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators

The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index also ranks Venezuela last out of 143 countries, highlighting systemic breakdowns in accountability, legal clarity, impartial justice and accessible governance processes.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index consistently ranks Venezuela among the most corrupt countries globally, with pervasive corruption undermining rule of law and investor confidence.

These governance indicators paint a picture of a country with weak institutions, fragile legal protections and entrenched corruption. Such systemic challenges exacerbate commercial risks and undermine the prospects for sustained foreign investment in Venezuela’s oil sector. The current reforms initiated in Venezuela and backed by Washington are just a small step in a long, complex and difficult process.

Having a law approved – or adopted under U.S. pressure – is far from sufficient, let alone a guarantee of success. Investors are looking for execution, oversight, institutional capacity and a coherent regulatory ecosystem before committing the billions required to rehabilitate an industry long starved of modern capital. This includes not just hydrocarbons legislation, but also supporting institutional architecture such as competent administrative capacity, consistent environmental and labor regulations, dependable judicial enforcement and transparent oversight mechanisms.

Some companies may try to protect themselves through contractual safeguards – for example, stabilization clauses that fix terms against adverse regulatory changes – and by embedding dispute-resolution provisions in agreements. But history offers a cautionary note. Even robust contract language did not prevent Venezuela from ultimately nationalizing or modifying terms in past cycles. Governments retain sovereign authority, and in practice, state actions often prevail despite contractual protections.

There is also a danger that overly lenient contractual terms, offered to entice investors, could backfire. In countries with a history of nationalism and weak governance, extremely attractive fiscal terms can raise expectations only to be reversed later if government institutions evolve unpredictably or if policy shifts occur after investment decisions have already been made.

While the current reform initiative marks an important policy shift away from the hardline state-centric model Venezuela’s past, it is still only one pillar of a long, fragile bridge toward restoring investor confidence and attracting meaningful long-term capital. Unless the reform is accompanied by strengthened institutions, credible legal guarantees and transparent, consistent implementation, the risk that the entire structure could falter remains high.

Scenarios

Most likely: Gradual, cautious engagement

Under this scenario, the recently proposed hydrocarbon reforms are implemented, but progress is incremental. Investors may cautiously reenter, starting with low-risk projects, attracted by improved contractual clarity, lower royalties and arbitration mechanisms.

Nevertheless, above-ground challenges remain significant: weak governance, limited administrative capacity, lingering legal ambiguity and political sensitivity to foreign involvement continue to create high execution risk. Companies are likely to adopt a phased approach. As a result, Venezuela could see a slow revival in production, but the country will likely continue to underperform relative to its resource potential.

Less likely: Rapid, bold investment surge

Reforms are implemented quickly and comprehensively, with credible enforcement, strong institutional oversight and predictable administration, considerably boosting investors’ confidence. Venezuela attracts substantial foreign capital, modernizes its infrastructure and notably expands production. But even here, the risk that some aspects of the reform are undermined or that political shifts reverse progress cannot be ignored.

Related Analysis

“Global oil market dynamics after U.S. intervention in Venezuela“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2026

Related Comments

“Venezuela sanctions, Iran risk, and the geopolitical premium in oil prices“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2026