Dr Carole Nakhle

Energy prices often attract disproportionate attention from news media commentators, policymakers and academics. The importance of oil for the global economy’s health became notable following the first oil crisis in 1973, which showed how politicized the subject had become. Nearly 50 years later, in a statement by the White House on October 18, 2022, high prices at the pump were labeled “Putin’s Price Hike,” even though it distorted a much more complicated reality. Energy is more than oil. Today’s energy crisis has seen price increases for all major fuels for multiple reasons and starting long before the invasion of Ukraine.

Energy prices started to increase significantly from mid-2021. As governments and central banks worldwide announced emergency packages and generous growth-stimulating policies, and as the global economy gradually recovered from the major blow of Covid-19, demand for energy – for transport and industrial use alike – received a significant boost.

Energy prices explosion

Meanwhile, supply faced a long list of constraints across all primary fuels – from supply chain bottlenecks partly related to Covid-19 related restrictive rules to voluntary historic production cuts in oil markets courtesy of OPEC+ to investors’ reluctance to finance investments in fossil fuels in the wake of the climate debate. Outages at nuclear power plants of important producers like France, drought in leading hydropower producers like Norway, and of course, the geopolitical shock of the war in Ukraine, which significantly disrupted energy trade in Europe and elsewhere, exacerbated the situation.

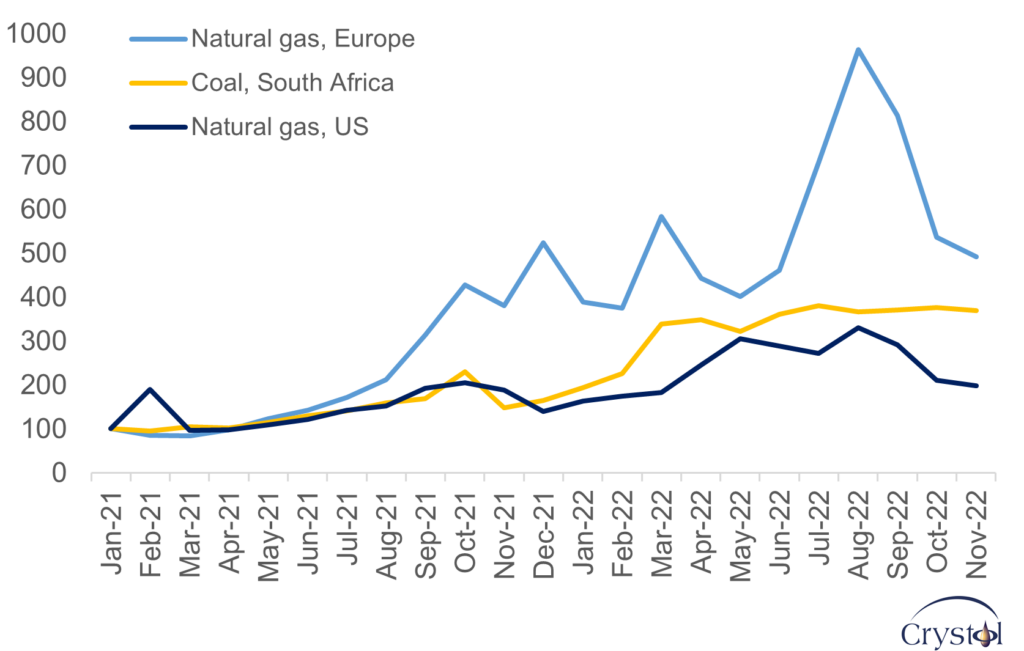

Energy prices hit historical highs, particularly European gas prices where Dutch Title Pricing Facility (TTF) hub, the benchmark European gas price, set a record of nearly 340 euros per megawatt-hour (MWh) on August 26, 2022, nearly 11 times the price recorded one year earlier. However, the data clearly indicates that the war in Ukraine amplified an already growing mismatch between energy demand and supply: it is not the one factor that caused it.

Energy price indices, January 2021=100

Source: World Bank

Between the first halves of 2021 and 2022, electricity prices increased by 7, 15, 38, and 57 percent in France, the European Union, Italy and Denmark, respectively. In June 2022, gasoline prices in the United States hit an all-time national high. High energy prices cause social hardship because the expenses for fuels (used for driving or heating) as a share of incomes are much higher for low-income groups than for the relatively wealthy. They also may cause economic problems by disadvantaging energy-intensive industries and regions. However, one of their main economic consequences comes from high energy prices being a powerful driver of higher inflation.

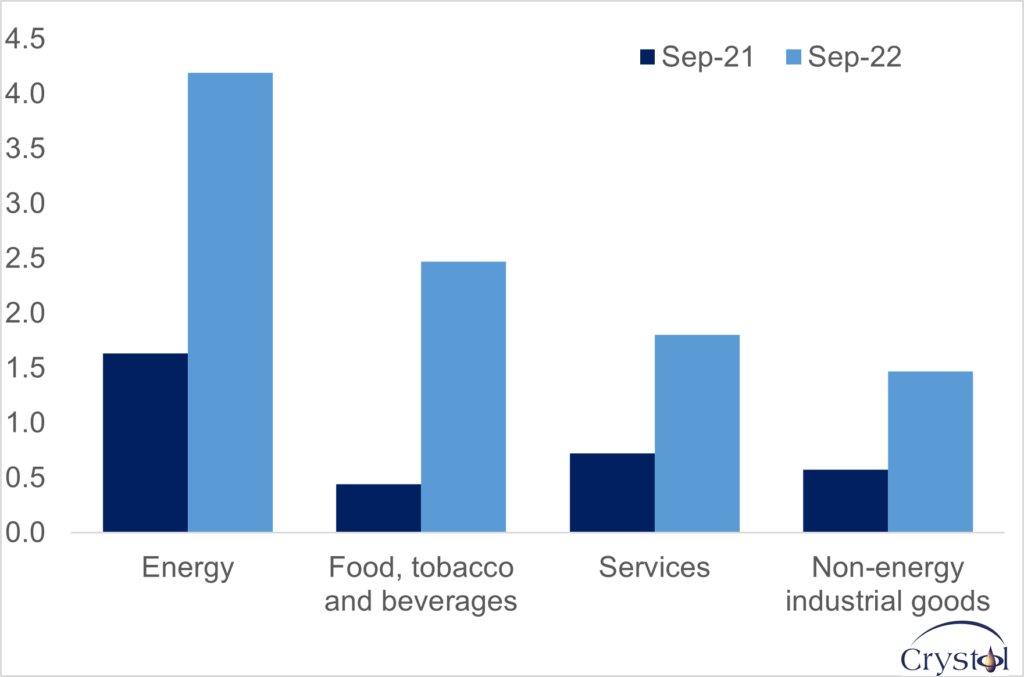

Along with elevated food prices, energy prices have fueled inflation. The eurozone headline inflation increased from 4.4 percent in October 2021 to a record 10.6 percent in October 2022. In many EU member countries, inflation rates had already hit double digits earlier. October consumer inflation jumped to 11.1 percent in the United Kingdom, a 40-year high. Energy prices have been the most significant contributor.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the weight of energy goods and services in the consumer price indices (CPI), which measures the monthly change in prices consumers pay, varies between 5 and 15 percent in most of Europe. Despite these modest shares, given the fast rise in energy prices in an otherwise still relatively stable environment, energy items directly accounted for about half of the annual CPI inflation rates in May 2022.

Once high energy prices are publicly perceived to translate into high inflation rates, these economic consequences add to their broader, negative ramifications. The sum of their adverse effects can quickly dilute a leader’s popularity, fuel social unrest and even topple governments.

Therefore, policymakers feel coerced to “do something” to ease the burden of high prices on households and businesses and subsequently appease public discontent. However, some of the measures pursued clash with previous commitments, and others can be counterproductive.

Contribution to euro area inflation rate by selected aggregates, %

Data Source: Eurostat

Energy-inflation nexus

The link between energy prices and inflation is particularly significant today because of the global economic situation. Around the world, central banks are increasing interest rates in an attempt to bring down accelerating inflation. This inflation has been caused by years of loose monetary policies and profligate spending after the 2008 crisis and to combat Covid-19 – and by energy prices. These prices are now accelerating inflation and making it harder to fight it. And all around the world, the concern is that the rise in interest rates necessary to fight inflation may cause local or even a global recession.

The channels through which changes in energy prices affect inflation are complex and can change over time and across countries. A distinction is often made between first- and second-round effects, in addition to differences between net importers and exporters, developed and developing economies, taxers and subsidizers, and households and businesses, which result in differing impacts across economies.

For instance, according to the IMF, energy prices account for the lion’s share of inflation in most advanced European economies. In contrast, they account for a smaller share in several emerging European economies where the recovery from the pandemic has progressed faster. Also, net importers of energy are facing worsening terms of trade. And energy-intensive industries will be more exposed than others.

The first-round effect of high energy prices refers to the increase in the cost of living and purchasing power, as transport and heating, for instance, become more expensive. In this case, the larger the share of energy in total consumption expenditures, the stronger the impact of higher energy prices is on the CPI. In this respect, because they spend a relatively large percentage of their income on energy, poor households are particularly hard hit when energy prices surge.

With the second-round effect, higher energy prices translate into higher production costs, including for non-energy goods and services, which firms try to pass on to consumers. They can also increase wages, which in turn fuels inflation. The larger the second-round effects, the more hawkish central banks are against inflation. To better understand the second-round effects, economists look at the core inflation rate that excludes the direct effects of increases in the prices of energy and food. (In practice, such a distinction is not clear-cut.)

Urge to control prices

Although demand eventually responds to prices, that adjustment does not happen instantly; consumers, for instance, cannot immediately find an alternative to their gasoline-burning cars or replace their gas boilers – what economists describe as inelastic demand. And because energy is necessary to meets basic needs, governments feel the urge to step in during times of crisis to alleviate the burden of higher prices, particularly on households.

In particular, European governments have pursued a wide range of measures to address the crisis, though most have been “broad-based price-suppressing measures, including subsidies, tax reductions, and price controls,” as described by the IMF. In Spain, France, Austria, Denmark and the UK, for instance, caps on electricity prices have been introduced, while cash payments to low-income households are given in Austria, Denmark, France, Italy and Sweden.

Tax relief on gas and electricity bills has also been offered, such as in Austria (90 percent cut in gas and electricity tax) and Italy (25-40 percent tax credits to companies based on their energy needs). These measures carry a massive price tag: According to economy think tank Bruegel, since September 2021, 674 billion euros have been allocated and earmarked across European countries to shield consumers from rising energy costs.

Costly downside

However, they raised alarm bells. Economists and international organizations have repeatedly called for governments to avoid shielding domestic users from higher prices. The reasons for these concerns are simple. Price caps on energy can be counterproductive because lower prices will increase energy consumption in a situation where there is a need to curb it, and subsidies increase liquidity in the system and have the potential to fuel inflation.

The IMF recommended that policy measures that mute the price signal should be avoided and wound down where they have already been introduced. Such measures, the financial agency warned, “are an inefficient tool to protect the economically vulnerable, are fiscally costly, and they mute the demand adjustment to the price shock (including energy-conserving behavior and energy efficiency investments).”

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development made a similar call: “While relatively simple to introduce and communicate in general, measures that act to lower the price of energy are not targeted and weaken incentives to reduce energy use when supply is tight. If prices remain elevated, governments should shift to more targeted measures, including through the increased use of income support.”

The World Bank warned that after declining in the last couple of years, energy subsidies are coming back rapidly and at much higher levels than before Covid-19.

In recent years, the fight against energy price caps and subsidies, especially in more affluent countries, has also been fueled by climate concerns. These measures support fossil energy consumption, making it harder to limit the associated CO2 emissions.

Although energy subsidies have traditionally been concentrated in developing economies, they are now widespread in the richer countries as well. Since 2009 and until recently, the G7 and G20 committed to phasing out fossil fuel subsidies – a pledge that they repeated every year they met.

The policy responses to the current energy crisis conflict with that pledge. Ironically, in June 2022, the G7, an intergovernmental political forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the U.S., stated that “fossil fuel subsidies are inconsistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement” and reaffirmed their commitment to eliminate them by 2025. The irony is that many of the policy responses to the current crisis adopted by the same countries qualify as fossil fuel subsidies.

The gas price cap that the EU has been debating is another controversial measure. It would force suppliers to sell at the capped price. Aside from the technical complexity related to its application and adherence among all member countries, there is another roadblock. Countries like Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands have opposed it fearing it would encourage demand while decreasing supplies as sellers could halt shipment and divert their gas to more lucrative markets, thereby exacerbating an already dire situation.

Scenarios: Primacy of realpolitik

Another problem with the cocktail of measures that policymakers have introduced to shield their economies from higher energy prices is the potential clash between fiscal and monetary policies. The IMF’s chief, Kristalina Georgieva, put it clearly: “[I]f monetary policy puts the brakes on, fiscal policy should not step on the accelerator. Otherwise, they would be going in a very bad direction.”

For consumers, high energy prices are undesirable. But prices shape behavior and alter preferences. Distorting such signals through price controls and subsidies will simply lead to an inefficient allocation of resources. This is one plain fact that economists agree on. However, policymakers prefer to commit an economic misstep rather than a political one. After all, no president or prime minister ever won an election by promising higher energy prices.

Factbox: Disruption and intervention

- The recent surge in international fossil fuel prices will raise European households’ cost of living in 2022 by close to 7% of consumption on average (IMF).

- Higher energy prices alone are likely to reduce global output by nearly 1% by the end of 2023 (World Bank).

- In Europe, governments announced generous packages to combat the energy crisis, with the largest in Germany where, in October 2022, the parliament approved a 200 billion-euro energy relief plan compared to 45 billion euros, 17.2 billion euros, and 3 billion euros in France, the Netherlands and Portugal, respectively.

- EU energy ministers agreed to reduce natural gas use by 15% between August 1, 2022 and March 23, 2023, and electricity consumption by 5$ at peak hours.

Related Analysis

“Germany’s scramble to revamp its energy policy“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2022

“Thatcher’s energy plan was derailed – now we are paying a gigantic price“, Lord Howell, Sep 2022

“Energy policy confusion“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2022

Related Comments

“British government needs to move on to “war footing” over energy prices“, Lord Howell, Aug 2022