Dr Carole Nakhle

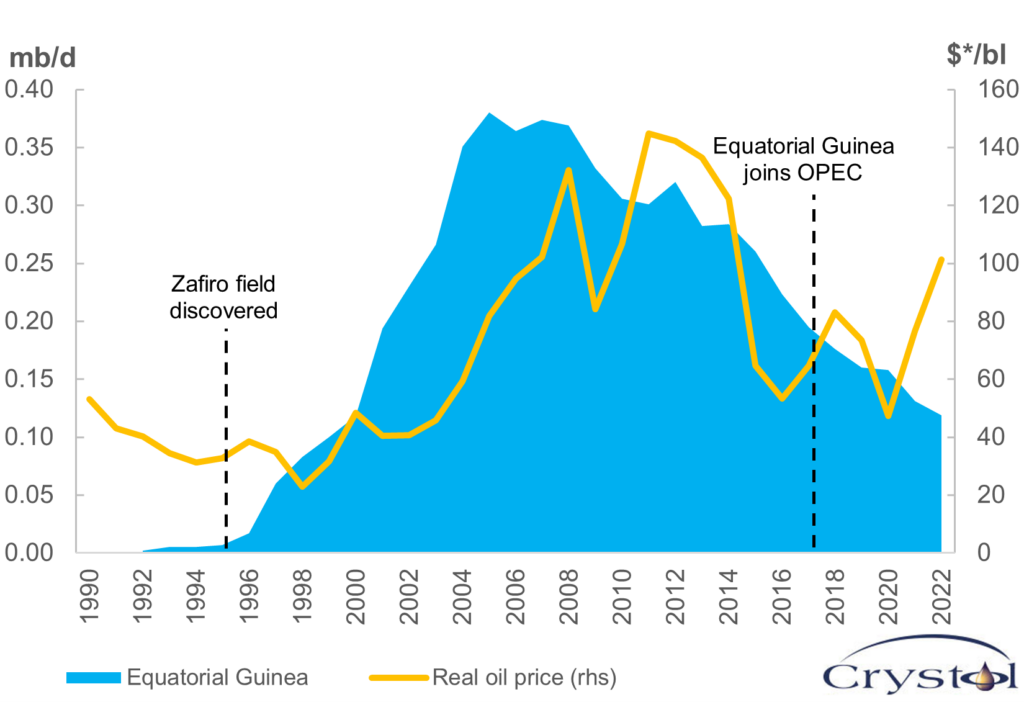

In February 2024, American oil giant ExxonMobil announced it was exiting the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, effectively severing a nearly three-decade-long relationship. The company played a leading role in the development of the oil sector in the African nation. In 1995, Mobil Corporation discovered the Zafiro oil field, and Exxon entered the scene after its takeover of Mobil in 1999. The Zafiro field turned the country into a net exporter of oil. At its peak, it accounted for more than half of Equatorial Guinea’s oil output, resulting in substantial economic benefits for the country.

ExxonMobil’s exit risks sending negative signals to other investors at a time when the government is keen on maintaining interest in its declining oil and gas sector. Darren Woods, CEO of ExxonMobil, said that the decision to leave the country is consistent with the company’s strategy of reducing capital spending and focusing on regions with higher growth potential, such as Guyana and the Permian Basin in the United States. In other words, ExxonMobil did not see lucrative potential in the Equatorial Guinean oil sector. Meanwhile, the country’s ambition to become a regional gas hub, capitalizing on its location on Central Africa’s west coast, has yet to materialize.

The decline of oil and gas production and the shrinking of an already small oil and gas reserves base spell serious trouble for an economy that is notably reliant on the proceeds of fossil fuels. To lead the oil-dependent country out of this crunch, the government of Equatorial Guinea would need to succeed simultaneously in a number of tough challenges. One is attracting suitable investment to expand the oil sector domestically. Another is reaching agreements with neighboring countries on both gas supplies and joint field development. At the same time, essential institutional reforms and economic diversification also need to occur in the country.

Only this combined approach could help Equatorial Guinea reduce its vulnerability as the energy transition accelerates and marginalizes smaller oil and gas producers.

Marginal producer with small proven reserves

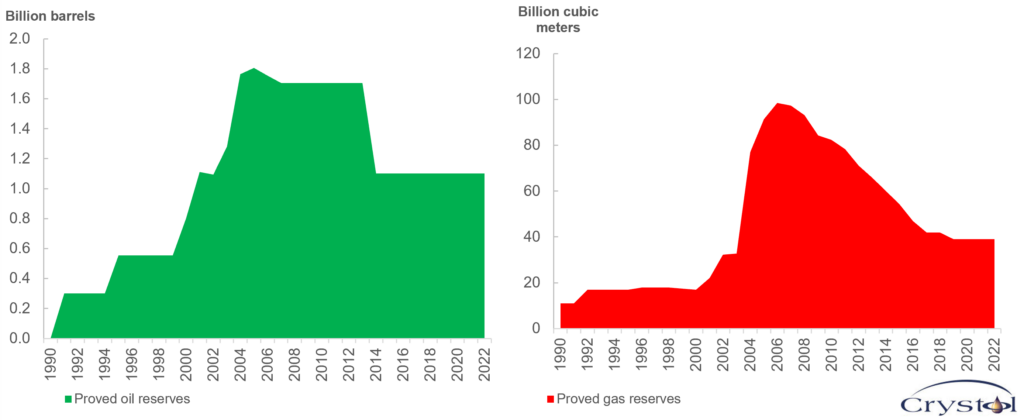

Equatorial Guinea is not particularly rich in oil or gas. Its proven oil reserves (1.1 billion barrels) account for about 0.07 percent of the world’s total and 0.9 percent of Africa’s, ranking 37th in the world and ninth in the continent. It has not even half of the reserves of its neighbor Gabon and only a fraction of those of Nigeria, with which it shares maritime borders.

Equatorial Guinea, hydrocarbon reserves

Source: OPEC

Its proven gas reserves are even smaller on both global and regional scales. At only 39 billion cubic meters, they are equivalent to what the United Kingdom consumed in 2022. This leaves Equatorial Guinea ranked 50th globally (at 0.02 percent of global reserves) and ninth in Africa (0.2 percent).

The country’s oil and gas output comes exclusively from its offshore fields. Oil production averaged 0.119 million barrels per day in 2022 (or 1.7 percent of Africa’s production, and 0.1 percent of the world’s), but that still puts the country among the continent’s top 10 oil producers. Equatorial Guinea is the smallest producer within OPEC.

Ranking of Africa’s energy producers, 2022

Source: OPEC

Favorable conditions for energy exports

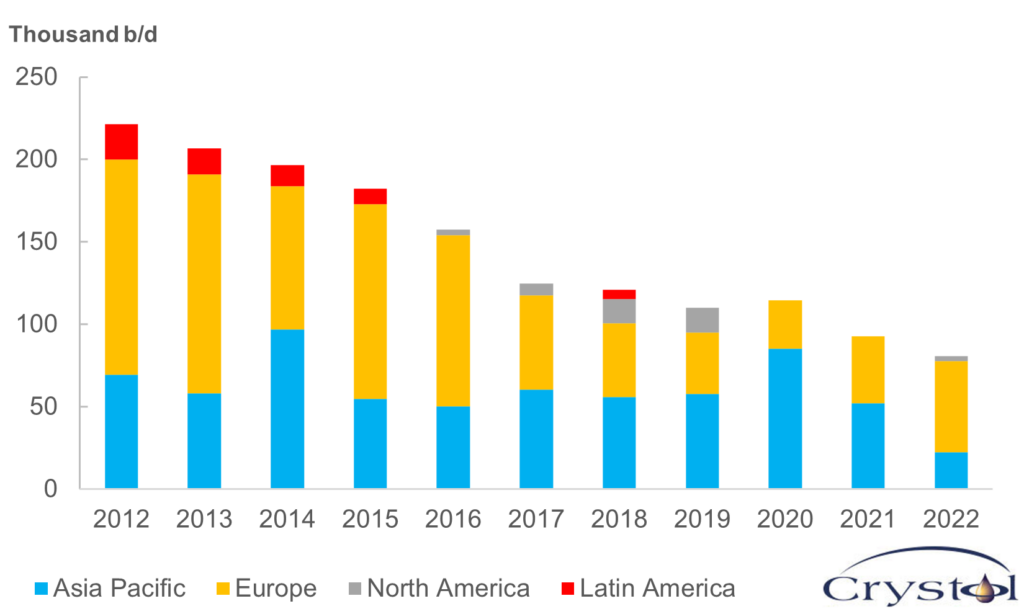

Equatorial Guinea’s domestic energy consumption is small – its population of around 1.75 million consumes only 4 percent of the country’s oil output – which creates a sizeable surplus for exports. The country’s location at an almost equal distance between the markets in Europe, Asia and North America gives it an additional advantage.

Equatorial Guinea’s crude exports by destination

Source: OPEC

Although natural gas plays a larger role in the country’s energy mix (82 percent compared to 12 percent for oil) and electricity mix (67 percent versus 0.6 percent for oil), the local gas market is also small. That allows Equatorial Guinea to export the surplus in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG) through its only liquefaction plant (operated by the company EG LNG in the capital city of Malabo). The plant has a capacity of five billion cubic meters per year – equivalent to 0.8 percent of the global liquefaction capacity.

In 2022, Equatorial Guinea ranked 15th among LNG exporters globally. Its gas exports are more diversified than its oil exports, almost equally targeting the markets in Europe (37 percent), Asia-Pacific (34 percent) and Latin America (29 percent).

Historically, the oil and gas sector generated substantial wealth for this small nation. Between 2007 and 2014, Equatorial Guinea was Africa’s richest country on a per-capita basis – after being one of the poorest in the continent – and achieved an upper-middle-income status. Hydrocarbons account for nearly 50 percent of both exports and gross domestic product (GDP) and over 70 percent of government revenues (in 2022).

That high dependence highlights the peril Equatorial Guinea is facing. According to the World Bank, declining oil reserves and a failure to diversify its economy have been contracting the country’s output for almost a decade. Between 2013 and 2023, it shrunk at an average rate of 4.2 percent per year.

Short-lived boom followed by decline

Equatorial Guinea’s oil industry experienced a golden era from the mid-1990s to 2005, starting with the discovery of Zafiro’s oil field. ExxonMobil held a 71.25 percent interest in the field, while state-owned Guinea Equatorial de Petroleos (GEPetrol) and the government have 23.75 percent and 5 percent participating interests, respectively.

The field began production in record time in 1996, which was followed by several discoveries. However, the rapid ramp-up in production and a short-lived peak in 2005 of 380,000 barrels per day was followed by a substantial decline. In 2022, oil production contracted to levels last seen in 2000, nearly a third of the peak. There are no signs that the decline will be reversed under existing conditions. The main reason for that decline can be attributed to the scarcity of discoveries: the last discovery made was in 2007, in the Aseng field.

In 2017, Equatorial Guinea joined the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), becoming the fourth sub-Saharan country to join the producers’ organization after Nigeria (1971), Gabon (1975) and Angola (2007). Interestingly, the other three joined OPEC when their oil outputs were experiencing rapid expansions, whereas Equatorial Guinea joined when its production was at half its peak. The World Bank explains the country’s decision to join OPEC as an attempt to boost foreign investment and technology transfers from other member countries, especially those in the Persian Gulf.

Equatorial Guinea’s oil production and oil price

Source: OPEC, Energy Institute *US$ 2022

Natural gas has performed relatively better, even though the gas era started with the discovery of the Alba gas field in 1984, and production began in 1991 – earlier than oil production. The field still accounts for approximately 45 percent of the country’s daily output, and it is its sole supplier of feed gas to its LNG plant in Malabo, which has been operational since 2007. The aging of the Alba field has reduced the total output of the country: production peaked already in 2013, but the decline has been smoother compared to the precipitous fall in oil production. Meanwhile, the growth in domestic demand is further reducing the country’s export capacity.

In the hope of safeguarding Equatorial Guinea’s gas exports and attracting international interest, its government set forth a vision of establishing the country as a regional gas liquefaction hub, receiving the commodity from domestic fields and also from neighboring Cameroon and Nigeria for processing and exporting it to international markets.

Such a plan would extend the lifespan of the country’s LNG facility, which is in jeopardy since gas supplies from the Alba field have begun to decline. The project, however, is progressing at a slow pace. It faces hurdles that include finalizing agreements with neighboring countries on the development of cross-border oil and gas fields, securing potential supplies and building connecting pipelines.

Trying a different approach

In 2019, Malabo launched a licensing round to allocate 27 oil and gas blocks. In the end, three blocks were awarded to small players, such as Africa Oil Corp, a Canadian oil and gas company focused on Africa, and Panoro Energy, a London-based independent company. Following the licensing round, the then Minister of Mines and Hydrocarbons Gabriel Mbaga Obiang Lima was quoted as saying, “We will plan to do another licensing round and it will be done differently.” In 2023, the government adopted an “open-door policy” whereby any company can express interest and enter into direct negotiations with the government. One block was awarded in 2023 to Panoro Energy as a result of such negotiations.

An open-door strategy is usually adopted when the success of a bidding round is doubtful. Generally, bidding rounds are the superior and most widely-pursued strategies for allocating oil and gas licenses. However, their success hinges on several factors – some that go beyond a country’s borders, such as prevailing oil and gas prices. Others relate to the country’s potential. When prices are high and the country’s oil and gas sector has a promising outlook, then competition among bidders tends to be strong, resulting in a windfall for the government.

A failed bidding round that does not attract sufficient interest can damage a government’s bargaining position. To avoid such an outcome, governments use direct negotiations. However, the problems with this policy are the lack of transparency in allocating the licenses, and that there is no guarantee of the best outcome for the government as a competitive bidding round would offer.

Scenarios

Most likely: Poor prospects for oil production rebound

The departure of ExxonMobil from Equatorial Guinea casts further doubt on the outlook of the country’s energy sector. To reduce the reputational damage and improve the appeal of investing in the country, the government announced several fiscal incentives effective as of 2024, including slashing the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent. Such measures might help, but not enough to compensate for the limited potential for generating the kind of rewards a big player typically seeks. Indeed, it was reported that Malabo has been trying to convince Italian energy firm Eni, a major player in Africa, to take over ExxonMobil’s stake in Zafiro, but so far with no success.

Most, if not all, governments prefer to see big industry players involved, given the financial and technical resources that smaller players are lacking. It also helps in new deal negotiations. However, a change in industry structure is expected when the maturity of an oil and gas province advances. The government can tailor its strategy to accommodate such a new phase.

With aging assets, technically challenging small fields and a high cost of exploiting them, Equatorial Guinea is among the producers that are exposed to energy transition pressures. The government’s key concern is, therefore, to extend the longevity of its all-important hydrocarbon sector by trying to engage not necessarily the biggest names in the industry but the most agile actors.

Facts & Figures

The former Spanish colony, located between Cameroon and Gabon, consists of the Rio Muni region on the mainland overlooking the Gulf of Guinea plus five islands, including Bioko where the capital Malabo and the LNG terminal and liquefying plant are located.

- Area: 28,051 square kilometers; slightly smaller than Belgium.

- Population: estimated between 1.61 million and 1.75 million.

- GDP per capita (PPP): $19,850 in 2008; $7,182 in 2022.

- President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, in power since 1979, is one of the world’s longest-ruling heads of state.

- Oil production increased at a rate of 26% per year between 2000 and 2005 (compared to Africa’s average rate of 4.7% during that period).

- Production from the Zafiro oil field peaked in 2004 at around 0.28 million barrels per day; in 2022, water leaked into a production vessel at the Zafiro field, forcing the platform to be retired two months later.

- Economic prospects: The IMF projects the country’s economy to continue declining until 2028 due to dwindling hydrocarbon output, stalled structural reforms, weak governance and significant corruption vulnerabilities.

Related Analysis

“Why Angola left OPEC“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2024

“Libya’s uphill struggle to attract oil investment“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2024

Related Comments

“Could the Red Sea Remain a No Go Route for Years?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2024

“Impact of geopolitics and elections on global oil markets“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2024

“2024 oil market expectations“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2024