Dr Carole Nakhle

Iran remains a major oil producer, but its actual influence on global oil markets has declined considerably. This stems not only from sanctions, which have often fallen short of their goals, but also from fundamental structural changes in the global oil landscape. The rise of new producers, the diversification of supply chains and slower demand growth have all reduced the market’s sensitivity to any single country, including Iran.

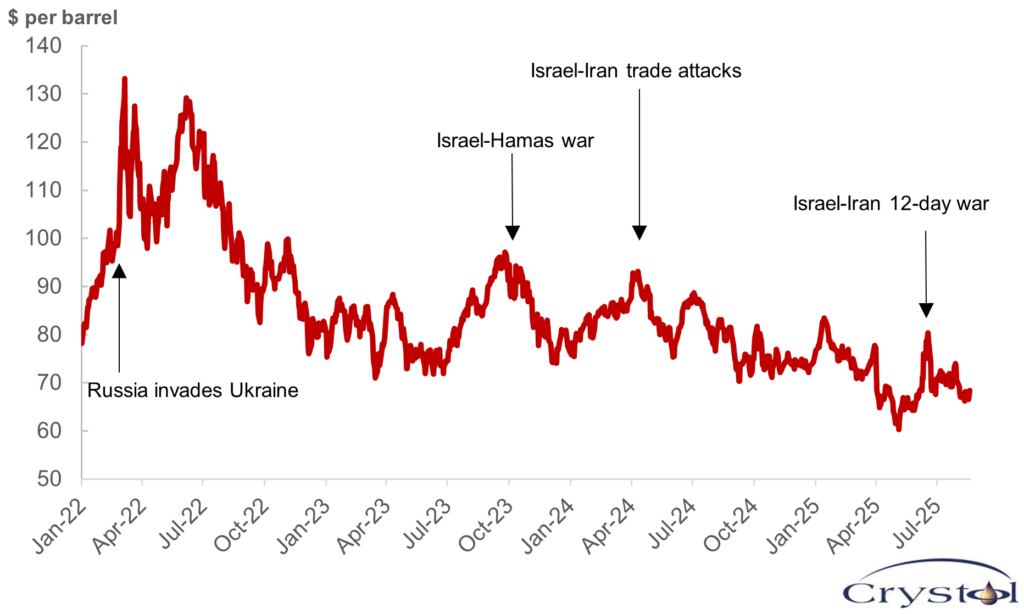

This shift was evident during recent tensions involving the United States, Israel and Iran. While the rhetoric and military posturing raised concerns, oil markets remained largely calm. Critically, there were no direct disruptions to oil production or trade routes – particularly the Strait of Hormuz, which Iran itself relies on to export crude. As a result, there were no significant supply losses. Oil prices spiked briefly, but the reaction was modest and short-lived. The oil market’s restraint reflected not Iranian deterrence or strength, but an increasing global capacity to absorb shocks.

Nevertheless, Tehran was eager to project an image of resilience and victory. Yet behind the political narrative, its sway in oil markets and its ability to influence prices or global supply dynamics has steadily eroded. The strong cards it once held as a producer have been weakened by internal issues, including chronic underinvestment, and more importantly, by external factors beyond its control.

Sanctions have undoubtedly constrained Iran, but they are porous. China’s continued purchases of Iranian oil, often at a discount, and its role in helping Iran circumvent restrictions have kept export volumes afloat. Nonetheless, this has not translated into real market power. With enforcement spread thin and global supply tightening at times, Iran has remained relevant but not dominant.

If sanctions on Iran are lifted, neither a rapid surge in production nor exports is likely. The country is already producing and exporting at relatively high levels, and any further increase would require substantial investment and time. Conversely, if sanctions are tightened, Iran’s economy would face further strain, but the global oil market would be unlikely to experience a major disruption, particularly if other Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) members continued to raise output.

Spot Brent oil price

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

If stricter sanctions on Tehran coincide with a substantial curtailment of Russian oil, the world’s third-largest producer, Iranian barrels could temporarily gain strategic value. Still, this effect would probably be short-lived, as other producers, including the U.S. and Gulf states, can compensate. In short, the global oil market is well-supplied.

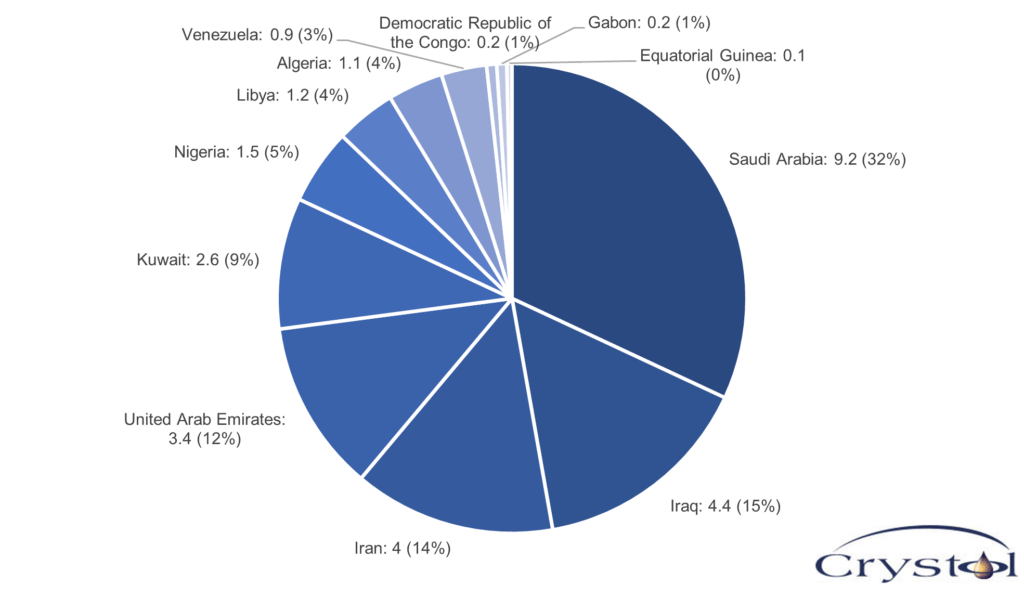

Iran is rich in oil and gas

Iran possesses the world’s fourth-largest proven oil reserves, accounting for 9 percent of the global total, behind Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Canada. It also has the second-largest proven natural gas reserves, with a 17 percent share, second only to Russia. It is the third-largest crude oil producer within OPEC and is the fourth-largest exporter.

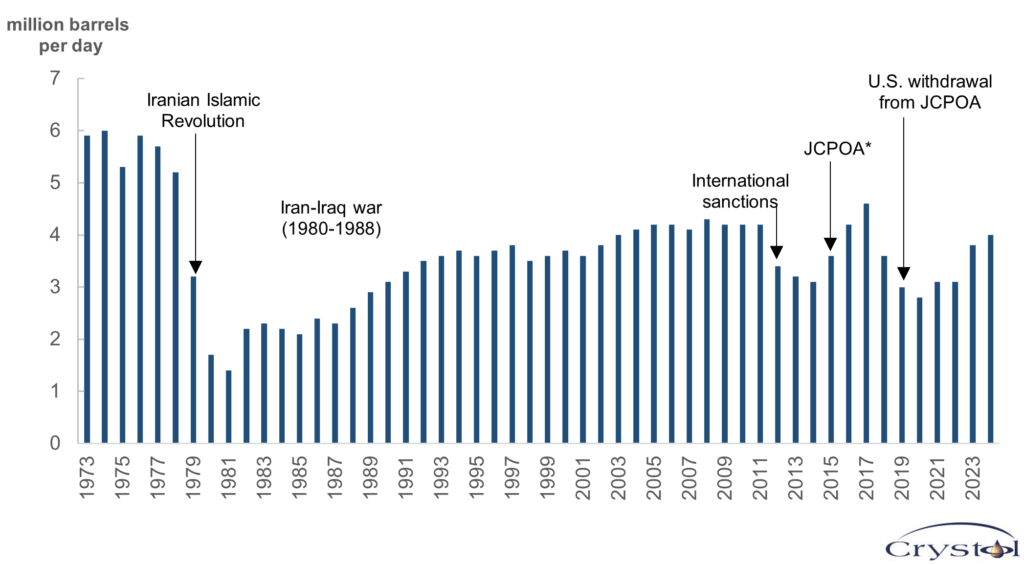

As a founding member of OPEC, Iran once held considerable influence within the organization, at times nearly rivalling Saudi Arabia’s dominance. At its peak in 1974, Iran was producing over 6 million barrels per day (mb/d), second only to Saudi Arabia’s 8.4 mb/d, while Iraq trailed at just 1.9 mb/d. However, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), prolonged sanctions and limited foreign investment have since constrained the country’s production potential.

OPEC member oil output (mb/d) and share

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

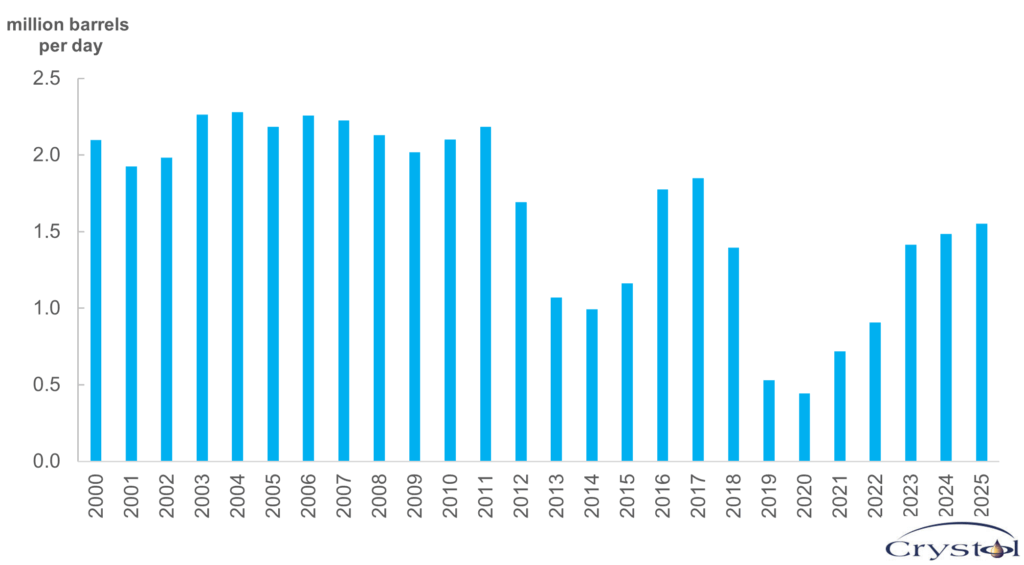

Despite these setbacks, Iran has repeatedly demonstrated resilience. Following the imposition of sanctions on its energy sector by the U.S. and the European Union in 2011 and 2012, the country’s oil exports were cut in half by 2015. But after the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed in 2015, where Iran agreed to limit its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of economic penalties, oil production rebounded swiftly. Within two years, output rose by 1.3 mb/d, and crude oil exports increased by over 1 mb/d within a year, returning to pre-sanctions levels.

The U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 during the first administration of President Donald Trump and its reinstatement of unilateral sanctions targeting Iran’s oil sector caused another sharp decline. Production fell by 1.9 mb/d within a year, and in October 2020 reached its lowest level since 1989.

Even so, Iran has gradually rebuilt output, recording one of the largest increases in oil production among OPEC members between 2021 and 2024. Notably, Iran is exempt from OPEC production quotas due to the ongoing sanctions, allowing it to maximize production and exports. In 2024, its oil output reached a post-sanctions annual high of 4 mb/d.

China has helped Iran evade sanctions

Iran’s oil exports have surged in recent years, tripling from approximately 400,000 barrels per day during the height of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign to around 1.5 mb/d in 2024. This resurgence has been enabled by a combination of lax sanctions enforcement and Iran’s persistent efforts to circumvent restrictions, often with the support of key trading partners such as China, the world’s largest crude oil importer.

Today, China is the primary destination for Iranian oil, while smaller volumes are also directed to countries like Syria, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. To avoid detection and obscure the origin of shipments, Iran relies heavily on a so-called “shadow fleet” of tankers that operate without transponders and often engage in ship-to-ship transfers, tactics that Russia has since emulated.

Iran crude oil production (mb/d)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

Financial transactions related to these exports are typically conducted in yuan through smaller Chinese banks, a system that limits the ability of Western authorities to track payments and enforce sanctions. Once Iranian oil reaches China, it is reportedly rebranded – often as Malaysian or Middle Eastern crude – and sold to independent Chinese refineries, known as “teapots,” which operate with fewer regulatory constraints.

It is widely believed that this trade arrangement has allowed Chinese companies to save billions of dollars. At the same time, Tehran has greatly benefited from the continued revenue. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Iran’s oil export revenues reached an estimated $43 billion in 2024, marking a $1 billion annual increase. This accounted for more than 57 percent of the country’s total export revenue in 2024, the highest share since the reimposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018, according to the World Bank.

Iran is a vulnerable giant

Despite its apparent resilience, Iran remains far more vulnerable than it appears. Although it continues to bypass sanctions, the crude oil it exports is sold at steep discounts, raising questions about the accuracy of reported revenue figures. As confirmed by the EIA, official estimates of Iran’s oil income do not reflect the price reductions offered to buyers of sanctioned crude. Iran has further increased its discounts to remain competitive with Russia in the Chinese market.

Iran crude oil exports (mb/d)

Source: St. Louis Fed

This reliance is compounded by the concentration of Iran’s export destinations. While Beijing has a diversified portfolio of energy suppliers, Iran is heavily reliant on China for its oil exports. The same vulnerability applies to non-oil trade. According to the World Bank, Iran’s top three trading partners, China, Iraq and the UAE, account for 60 percent of its exports and 70 percent of its imports.

Iran’s oil revenues in the financial year 2023-2024 reportedly fell well short of expectations, covering only about half of the amount projected in the national budget.

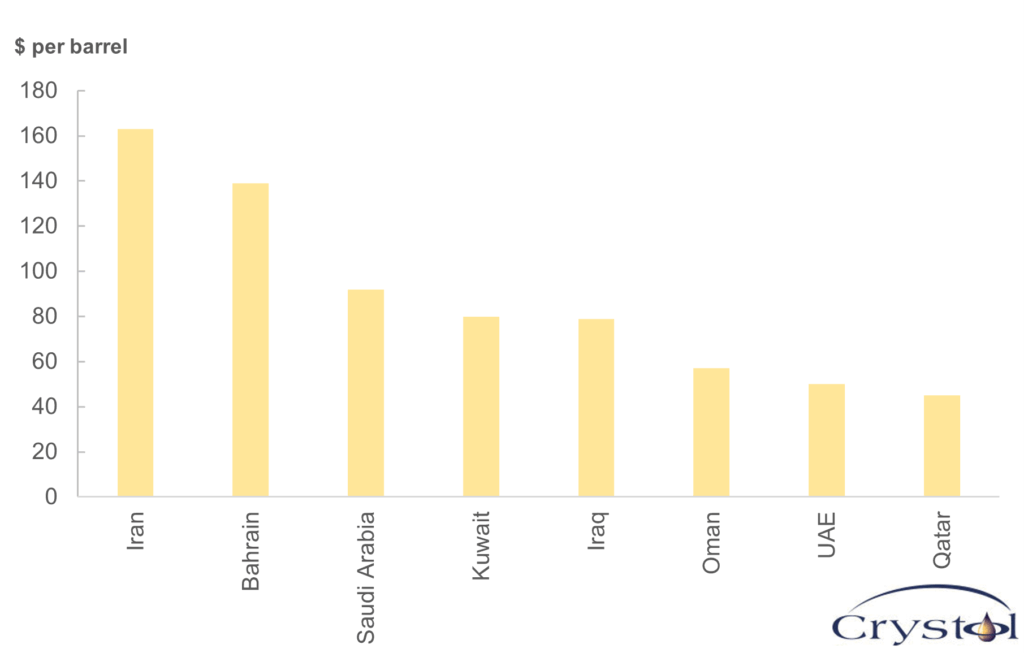

Fiscal breakeven oil price ($/bl) of Middle Eastern exporters

Source: International Monetary Fund

As a result, the government was forced to reduce spending to help contain the deficit. According to the International Monetary Fund, Iran would need oil prices to exceed $163 per barrel to balance its budget in 2025, the highest fiscal breakeven oil price among Middle Eastern oil exporters.

Structural constraints hinder Iran’s production

Although Iran’s oil production has increased in recent years, it remains well below its peak levels of the 1970s, even with the country’s large reserves and the advancements in drilling and extraction technologies since then.

Iran nationalized its oil industry in 1951, and the sector remained open to foreign investment for several decades. This changed after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when international investment in oil and gas was largely prohibited under the Iranian Constitution. The Iran-Iraq War further devastated the oil sector, leaving it in urgent need of rebuilding.

In response, the government adopted a more flexible stance toward foreign investment and introduced a new contractual framework known as the buyback contract. Under this model, international oil companies were permitted to invest only up to the point of first production, at which time the project would be transferred to the National Iranian Oil Company in exchange for a pre-agreed fixed fee.

However, these terms have historically been unattractive to international investors. Even after the JCPOA agreement in 2015, Tehran struggled to secure major international deals. This was due in part to internal divisions over the role of foreign capital in the energy sector, as well as lingering U.S. secondary sanctions that continued to limit access to global financial and banking systems.

In the absence of foreign investment, especially in recent years, Iran has increasingly relied on domestic firms to develop its oil projects. But these companies often lack the capital, advanced technology and technical expertise required to sustain output, particularly from mature fields. Sanctions have further exacerbated these challenges by limiting access to financing, curtailing technology transfers, raising trade costs and reducing overall competitiveness.

Meanwhile, as its production capacity has stagnated, other OPEC members, such as Iraq and the UAE, have expanded their market share, often at Iran’s expense.

One strategic asset Iran still controls is the Strait of Hormuz. Disruption to this key maritime passage could significantly affect worldwide energy supplies and prices, especially for major importers like China. Regardless of occasional threats from Iranian officials to block the strait, such actions have never materialized.

Scenarios

In early February, just weeks after returning to the White House for his second term, President Trump signed an executive order reinstating the “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran, aiming to coerce Tehran back to the negotiating table, a goal it has so far resisted. Tensions escalated further in June when Washington launched a targeted strike on Iranian nuclear facilities, signaling a hardline stance.

Yet, in a conflicting message, President Trump later said that China could continue purchasing Iranian oil, highlighting the ambiguity in U.S. enforcement and strategy. Against this backdrop, two broad scenarios emerge for the future of Iran’s oil sector

More likely: Cuts to Iranian oil exports will be compensated by other producers

If stronger penalties are introduced and enforced aggressively, Iran’s oil exports could fall from current levels. This would likely create upward pressure on global oil prices, assuming other factors remain unchanged. The situation could worsen if, concurrently, Russian oil exports are hit with tighter sanctions, intensifying global supply constraints. The combined loss of exports from two major producers would amplify the price impact.

The critical variable is how OPEC would respond. The group holds substantial spare capacity, particularly among Gulf producers such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have invested in expanding their output capabilities. At the same time, U.S. shale producers, typically quick to respond to price signals, would likely increase production if prices rise sharply. In this context, Iran’s absence from the market may be compensated for, at least partially, by others.

Less likely: Major post-sanction production increases

If sanctions are eased or lifted, Iran could increase its oil production and exports, but the upside would be limited. Unlike earlier periods when Iranian output dropped sharply, the country is already exporting around 1.5 mb/d and producing close to its post-sanctions high of 4 mb/d. Any meaningful expansion beyond current levels would require investment in infrastructure, technology and field rehabilitation, none of which can be achieved quickly.

Years of underinvestment and limited foreign involvement mean that production gains would be incremental, not immediate. Even during the brief window of relief in 2016, the country failed to capitalize on international interest, deterred by legal and regulatory hurdles that remain largely unchanged.

Related Analysis

“U.S. shale oil and gas: From independence to dominance“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2024

“The UK attempts to become a ‘clean energy superpower’”, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2024

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

Related Comments

“Experts warn of trade tensions on oil demand“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2025

“Why London is a great place for energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2025