Dr Carole Nakhle

Israel was on its way to becoming a reliable gas exporter. However, its ambitions may face a major setback with the October 7 Hamas attacks and the subsequent outbreak of war in the Gaza Strip. The hostilities have exacerbated the political risk of doing business in Israel and further jeopardize the outlook for the Eastern Mediterranean region as a potentially important player in global natural gas markets.

To assess Israel’s prospects as a gas exporter, it is worth looking at the state of its industry and recent history.

Israel first became a net gas exporter in 2020. By 2022, exports reached 10 billion cubic meters (bcm), nearly 50 percent of the country’s output. Most of those exports (64 percent) have been contracted to Egypt for 15 years, and the rest to Jordan. Having a new gas exporter at Europe’s doorstep was a welcome development for the European Union, which described exports from Israel, Egypt and Cyprus as strategic in supporting the 27-nation bloc’s quest to diversify gas sources.

The new chapter in Israel’s gas sector also featured heightened interest from international energy companies. For a long time, Israel’s gas sector was dominated by local and mostly small companies, while the large international players shied away from investing in the country, given the security risks and potential negative spillover on their investments in Arab countries.

However, in 2020, American energy giant Chevron entered Israel following its acquisition of Noble Energy, a small Houston, Texas-based company. Chevron, along with what is now known as NewMed Energy and their minority partners, were responsible for Israel’s giant gas discoveries – Tamar and Leviathan – in 2009 and 2010, respectively, and subsequently controlled virtually all of Israel’s gas reserves and production.

Then, in March 2021, Mubadala Energy, a wholly owned subsidiary of Mubadala Investment Company, which is owned by the government of Abu Dhabi, acquired a 22 percent stake in the Tamar field for more than $1 billion – the largest such deal between the United Arab Emirates and Israel at the time. In the country’s latest licensing round, launched in December 2022, five out of the nine companies that bid were reported to be new to the Israeli market and include BP and Azeri national oil company SOCAR. Also, in March of this year, BP and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) made an offer to buy a 50 percent stake in NewMed Energy.

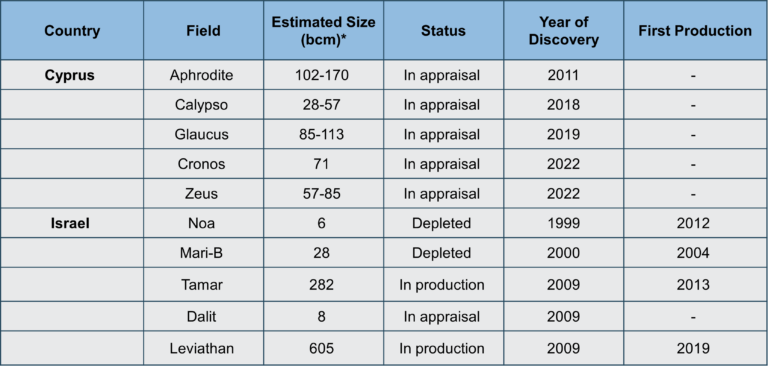

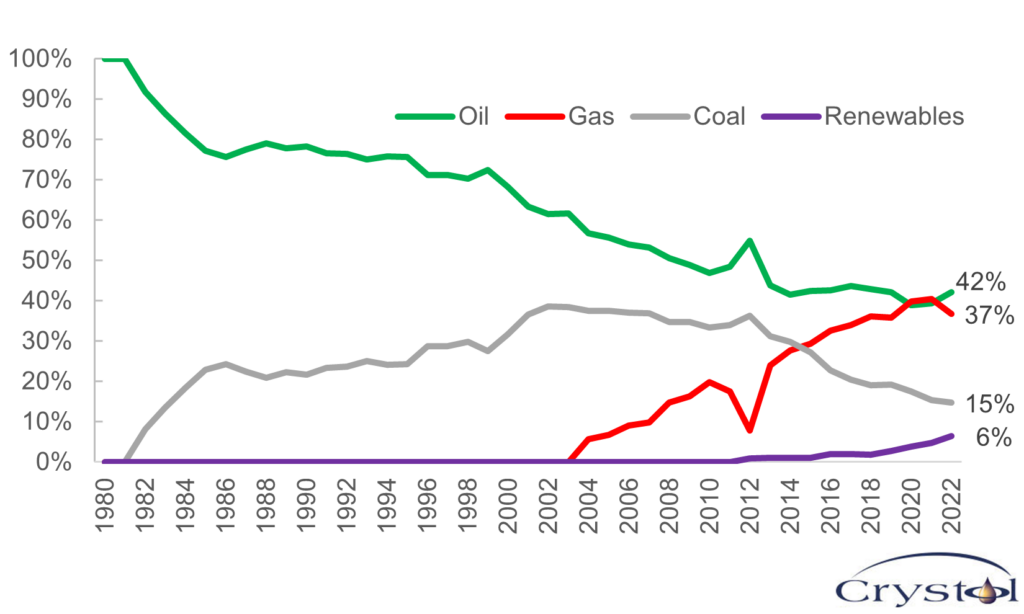

Natural gas discoveries in the Levant Basin

* Used for simplification due to technical differences in reporting field sizes during various stages of the field development.

Source: Cyprus Hydrocarbons Company, the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure of Israel, Chevron, Energean and various industry reports.

A rapid expansion of supply

Natural gas exploration accelerated in Israel following two initial small offshore discoveries, Noa and Mari-B in 1999 and 2000, respectively. However, it was the discovery of the giant Tamar and Leviathan fields that drastically changed not only the outlook for Israel’s energy sector but also redefined the role of the Eastern Mediterranean in the global gas trade.

Until 2003, Israel imported more than 96 percent of the energy it consumed, largely coal and oil. However, the beginning of domestic gas production played a crucial role in reducing the country’s energy imports, and with it the import bill and carbon emissions.

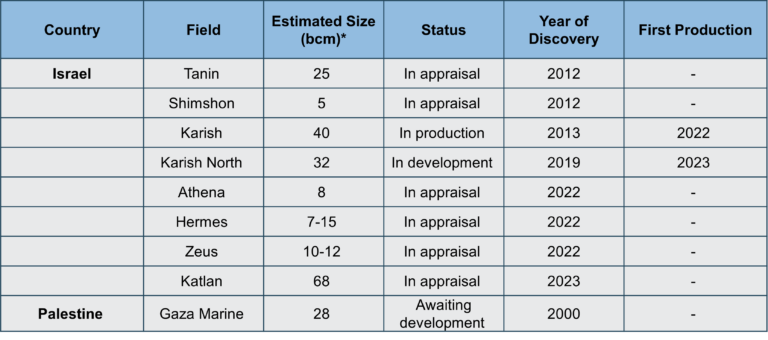

Between 2004 and 2012, Israel’s gas production reached a yearly average 1.2 billion cubic meters. That was, however, not enough to meet domestic demand, leading Israel to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) and gas from Egypt through the Arish Ashkelon, also known as East Mediterranean Gas (EMG) pipeline. Between 2013 and 2019, when production from the Tamar field started, domestic gas production hit a yearly average of 8.5 bcm, allowing Israel to become self-sufficient. Shortly thereafter, domestic production exceeded consumption and Israel became a net exporter. However, securing supplies for the domestic market has been the government’s priority. In 2013, the government kept most of the gas production for the domestic market. Lower-than-expected demand and a rapid increase in production led the government in 2021 to allow export of 40 percent of the supply.

Israel’s gas production-consumption balance and major milestones

Note: When Net>0, the country is a net exporter of gas; when Net<0 the country is a net importer of gas.

Source: Energy Institute, EIA

Limits to Israel’s natural gas production

Israel is not particularly gas-rich. It holds 600 billion cubic meters of proven gas reserves, equivalent to 0.3 percent of the known supply and less than 30 percent of neighboring Egypt. In 2022, it produced around 22 billion cubic meters, which is less than 1 percent of global production but nearly twice as much as the country consumed.

The Israeli market is small (equivalent to 18 percent of Egypt’s), while expansion plans from Tamar and Leviathan and potential new discoveries are expected to nearly double production by 2027, thereby supporting an increase in export capacity to 25-30 bcm by the end of the decade.

Israel has limited export options

Israel has exported gas through three routes to two destinations:

- The EMG pipeline, which runs directly offshore between Israel and Egypt. It has a capacity of 7-9 bcm per year to Egypt. The pipeline was originally built to transport gas in the opposite direction;

- The northern export line from the north of Israel to Jordan, connecting to the Arab Gas Pipeline in Jordan. The pipeline has an estimated capacity of 4 bcm; and

- The southern export line connected directly to Jordanian industrial facilities on the eastern side of the Dead Sea (with an estimated capacity of 4 bcm).

Israel’s gas exports to Egypt are of most relevance to the global gas trade, particularly the European market. Israel has relied on Damietta and Idku LNG plants in Egypt to reach global markets, as it does not have local export facilities. Despite the lack of market diversity, using Egypt’s export infrastructure has been the most practical export option for Israel.

Other export options have been considered – such as the EastMed pipeline – from Israeli and Cypriot gas fields to Cyprus, onward to Crete and then the Greek mainland before joining the existing Poseidon pipeline across the Ionian Sea to Italy. The project, however, has failed to raise the necessary funding to cover its price tag of 6 billion euros. Another option is an offshore pipeline from Israel to Turkey and from there connecting to the existing pipeline network between Turkey and Europe. Technically, the proposal is much simpler and probably cheaper than EastMed, but the relationship between Israel and Turkey has been patchy and their respective governments have clashed over Israel’s actions in Gaza.

Building an LNG export terminal domestically would give Israel more flexibility and a wider market reach. However, the location of onshore plants has been a thorny issue, particularly given the size and nature of operations involved. Floating LNG terminals might overcome those challenges. However, the costs and limited capacity of such plants have been the main drawbacks.

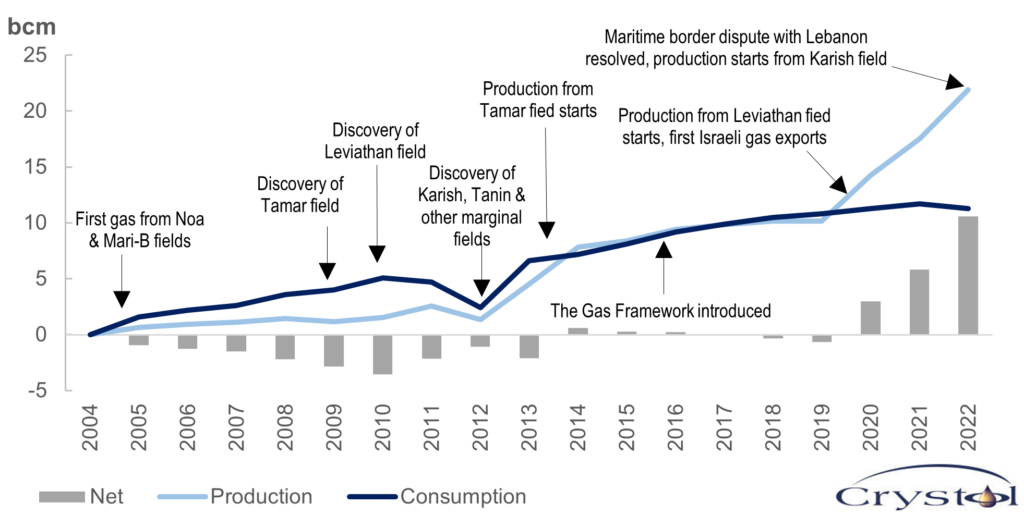

Evolution of Israel’s primary energy mix

Source: Energy Institute

Scenarios: Security concerns limit Israel’s export potential

There is also the security dimension. Israeli gas platforms and infrastructure are key targets for sabotage given their strategic importance to the country.

Following the attacks of Hamas, the Israeli government has ordered Chevron, the field’s operator, to temporarily halt production from the Tamar field, which could be targeted by rockets from Hamas, given its proximity to the Gaza Strip. The platform lies 25 kilometers northwest of the strip and 20 kilometers from the Israeli port of Ashkelon. The Tamar field produced 10.25 bcm of natural gas in 2022, nearly 91 percent of the country’s domestic gas demand in the same year.

This is not the first time that the field has been shut down. The first shutdown took place in September 2017, after a major technical failure forced the country to look for alternative sources of energy for one week. Then in May 2019, the Israeli security services informed the Ministry of Energy of a “credible threat” to the platform. Two years later, the Tamar field was again shut down amid a wave of unrest caused by tensions along the Gaza Strip.

Similarly, Ashkelon, a city located some 20 kilometers away from Gaza, was also targeted in the recent attacks. The city is home to the EMG pipeline. The pipeline was hit in 2011 on the Egyptian side, when Egypt exported gas to Israel and Jordan.

With its limited export options and given the fluidity of the political and security situation in Israel, it would be hard to label Israeli gas as secure, whether from an investment or market perspective.

Facts & Figures

- Natural gas is the second-largest fuel after oil in Israel’s primary mix, and the largest in the power sector, which is the biggest user of natural gas, accounting for 80 percent of domestic consumption.

- Gas became the fastest-growing fuel in the country; it entered the Israeli electricity mix in 2004 and in 11 years dethroned coal as the country’s largest source of energy for electricity.

- Israel is the only member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the region.

- Gas consumption in Israel (11.3 billion cubic meters in 2022) is less than 19% of Egypt’s (60.7 billion cubic meters in 2022).

- Even though Israel has made several discoveries since 2010, they have all been a fraction of the size of Tamar and Leviathan.

Related Analysis

“Cyprus’s gas remains stranded“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2023

“Egypt’s gas exports under threat“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Sep 2023

Related Comments

“Could OPEC+ Issue an Oil Embargo on Israel?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2023