Dr Carole Nakhle

The war in Ukraine has disrupted most – if not all – economic and energy market forecasts. In January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected that the global recovery would strengthen from the second quarter of this year. The war, however, has “set back” the global recovery, with economic effects “spreading far and wide like seismic waves that emanate from the epicenter of an earthquake,” declared the IMF in April. This is not because of either Ukraine’s or Russia’s economic importance – both countries’ economies will shrink severely, by at least 35 percent and 8.5 percent respectively – but because of their role in commodity markets and trade.

In the energy sector, Russia’s importance is indisputable. The country is the world’s largest oil and natural gas exporter. The constant fear of serious disruptions to its supplies and the lack of readily available alternatives have put significant upward pressure on energy prices. Although at some point the crisis will be resolved, its repercussions on the global energy trade will be much more lasting.

Following its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the subsequent imposition of sanctions by Western powers, Russia prepared for structural changes in its export markets and modified its plans accordingly. However, none of its published energy strategies and doctrines foresee losing its biggest market – now a likely scenario because of the war in Ukraine. The European Union is now working on becoming independent from all Russian fossil fuels imports by 2030. Even Germany, the main export destination of natural gas from Russia, has vowed to end its reliance on Russian energy “as soon as possible.” Russia will therefore have to reconsider its energy plans and brace itself for tougher competition.

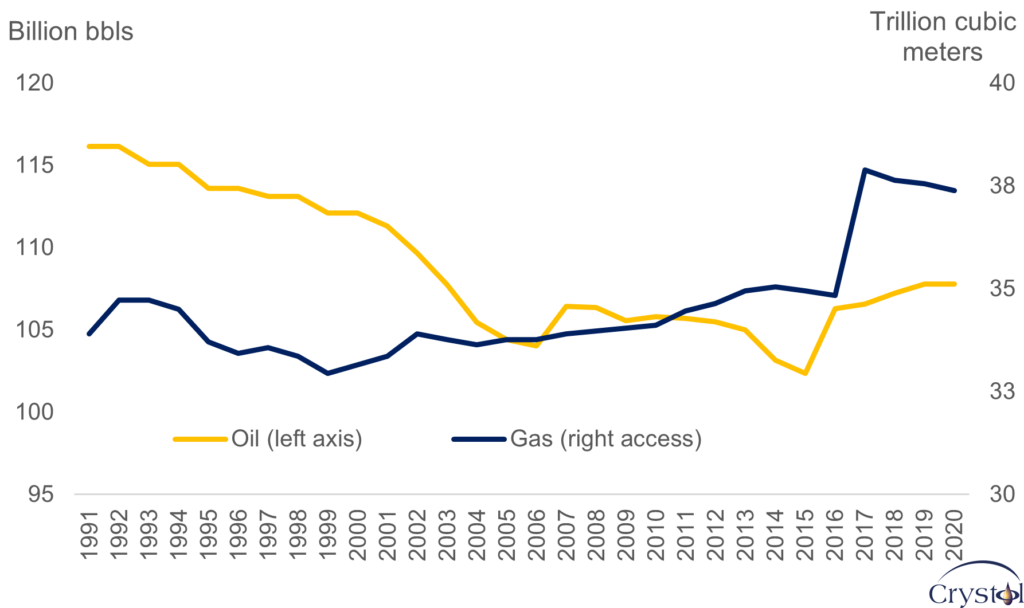

Russia’s proven oil & gas reserves

Data Source: BP

Russian perspective

Energy security is commonly analyzed from the perspective of consumers and energy importers and refers to reliable and affordable access to all fuels and energy sources. What is much less discussed, however, is energy security from the exporter’s perspective, which tends to revolve around the security of demand for their commodities as well as their vulnerability to external shocks. These external shocks can have a profound impact on the domestic economy, especially when it is largely dependent on revenues from those exports. Energy exporting countries therefore aim to boost their energy security by ensuring stable export volumes (preferably at high prices) and consequently stable inflow of energy export revenues.

The Russian government perceives energy security as one of the most important components of its national security. However, its approach to the matter has changed over time. That difference is clearly visible when comparing the government’s strategic documents on energy before and after the annexation of Crimea: before, the tone was measured and a subtle focus was placed on global cooperation; after, the wording became noticeably more defensive.

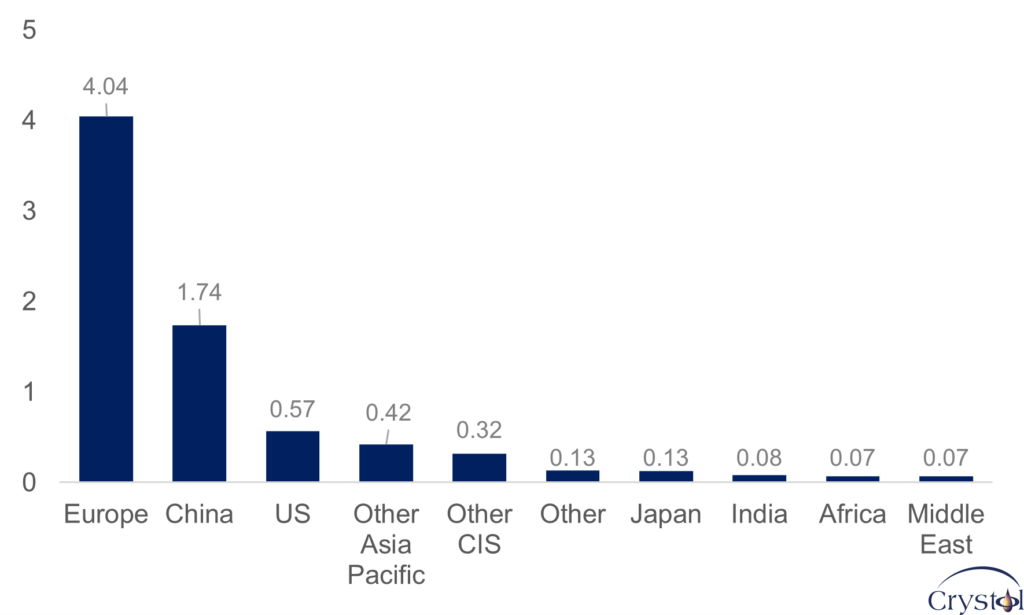

Russian oil exports by destination, 2020 - million barrels per day

Data Source: BP

For instance, the 2009 Energy Strategy for the period up to 2030 states that the long-term stability of energy markets and global energy security “must be provided without prejudice to any national interests whatsoever.” It also adds that “stable relationships with traditional consumers of Russian energy resources and shaping equally stable relationships on new energy markets are the most important vectors of the country’s energy policy in the sphere of global energy security provision in accordance with national interests of the country. … [The policy of Russia] is open and built on the principles of predictability, responsibility, mutual trust and taking into account interests of energy producers and consumers.”

In contrast, Russia’s Energy Security Doctrine of 2019 refers to Russia’s full participation in guaranteeing international energy security as “being hampered by restrictive measures introduced by several foreign states against Russia, including on the oil and gas sectors and the power system, as well as opposition from a number of foreign states and international organizations to energy projects that are under development with Russian participation.” It also highlights that one of the main sources of energy insecurity is the contraction of the traditional export market.

The doctrine was followed by the Energy Strategy to 2035, published in 2020, which includes increased exports, particularly to Asia and via liquefied natural gas (LNG) among government priorities. However, many factors will upset Russia’s plans: the international community’s response to the war combined with the legacy of 2014 sanctions, but also technical challenges related to Russia’s oil and gas production and exports as well as changing market dynamics in Europe and Asia.

Oil challenge

Russia is the world’s third-largest oil producer after the United States and Saudi Arabia and accounts for 12 percent of world production. However, its proven oil reserves rank sixth in the world (after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Iran and Iraq) and they have been depleting. In 2020, they were 7 percent lower than the levels recorded in 1991, whereas both the U.S. and Saudi Arabia increased their proved reserves by 114 and 14 percent respectively over the same period.

In its official energy documents, Russia’s most optimistic scenario is for oil production to plateau from 2024 to 2035 with a modest increase before then. In the more conservative scenario, oil production will decline over that period.

Russia’s difficulty in boosting its oil output stems from several challenges, including the depletion of its conventional oil reserves, as well as technological and economic sanctions since 2014. Russia has notable potential when it comes to shale oil, as it sits on the second-largest technically recoverable resource in the world after the U.S. However, the lack of access to Western technology and capital has prohibited the development of those resources and other conventional resources, particularly those located remotely or that are technically complex.

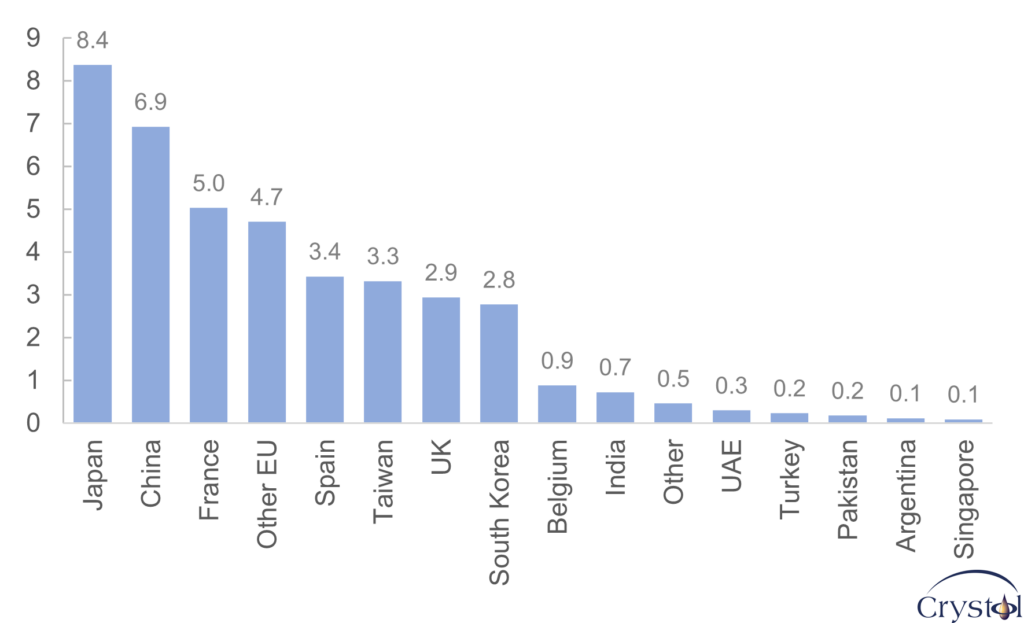

Russian LNG exports by destination, 2020 - billion cubic meters

Data Source: BP

The 2019 Energy Security Doctrine acknowledges the impact of the sanctions on restricting Russian energy companies’ access to modern technology, long-term funding and joint projects, thereby posing an economic and political threat. Under such circumstances, it was difficult to envisage significant growth in oil exports, particularly given the limited growth potential of Russia’s main market – Europe.

This sobering assessment came before the war in Ukraine. Now, however, the outlook for Russia’s oil industry has become bleak. The exodus of Western oil companies including oil field service providers, the new economic sanctions that dwarf those imposed in 2014 in terms of severity and reach, and the likely loss of the European market only spell trouble.

Gas potential

Russia seems to be pinning its hopes on its gas industry. The country is the world’s largest gas exporter and second-largest gas producer after the U.S. It also sits on the world’s largest proven gas reserves, which, unlike its oil reserves, have been growing rapidly. In 2020, they were 10 percent higher than their levels in 1991.

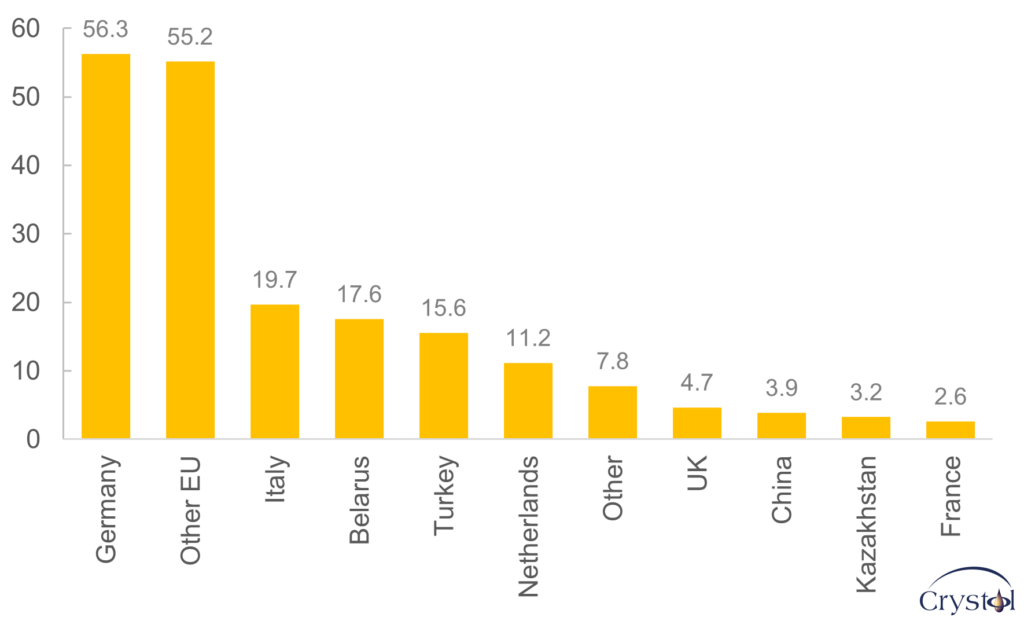

Russia’s Energy Strategy to 2035 forecasts significant growth for both gas production and exports – pipeline gas and even more so liquified natural gas, with Asia absorbing an increasing share of those exports. Currently, one pipeline – the Power of Siberia – connects Russia’s far eastern gas fields to China. The pipeline was agreed upon in 2014 (unlikely to be a coincidence), began operating in 2019 and has an annual capacity of 38 billion cubic meters (bcm). In February 2022, Russia announced a 30-year contract to supply gas to China via a new pipeline called the Power of Siberia-2, which has a capacity of 50 bcm and would supply China from the West Siberian gas fields via Mongolia. The pipeline is expected to be operational in 2030.

In parallel, Russia has been expanding its LNG exports and is among the four largest LNG exporters in the world (after Qatar, Australia and the U.S.), although LNG exports are still small compared to the country’s traditional pipeline business. In 2021, LNG exports stood at 17 percent of total exports of Russian gas. However, due to the relatively low costs, large resource base and geographical positioning, Russian LNG can be among the most profitable.

Russian pipeline exports by destination, 2020 - billion cubic meters

Data Source: BP

The Crimea sanctions limited Russia’s access to sophisticated LNG technologies but domestically produced LNG export technology has been given explicit support in the government’s road map on the localization of critically important energy equipment for mid- and large-scale LNG projects. Such an import substitution policy has been successful to a certain extent. Novatek, for example, was successful in developing its own liquefaction technology, “Arctic Cascade,” which is already been applied in the expansion of the Yamal LNG project and the Obsky LNG project. Gazprom is also developing its own liquefaction technology for large-scale LNG projects but has yet to implement it.

However, as with oil, the reaction of the international community to the war in Ukraine will delay or limit the realization of Russia’s potential LNG expansion plans.

No guarantee

Russia has been preparing for a shift in the geography of energy demand toward Asia and a slowdown in growth in the European market, a trend that has accelerated since 2014. However, Moscow’s strategy is not based on market substitution but on diversifying export destinations and routes to minimize the threats to its energy security.

What Russia did not prepare for is a complete loss of the European market – a difficult scenario to envisage but one that is becoming increasingly probable. For instance, in the worst scenario of the Energy Strategy, Russia expected gas exports to Europe first to increase to 2025 after which they would start to fall. However, even then, Europe would continue to absorb a significant share of Russia’s gas exports through 2035.

If Europe delivers on its recent promise to be free of Russian oil and gas imports by 2030, Moscow will have a significant surplus capacity to divert elsewhere, with Asia being the main destination. That, however, would make Russia too exposed to one market, jeopardizing its export diversification strategy.

Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the Asian market would absorb additional oil and gas exports that Russia would divert away from Europe, especially in the light of existing supplies coming from elsewhere, including from the Middle East. When it comes to LNG, major producers have all planned to ramp up their presence in key markets. These include the U.S., Qatar and East Africa, just to name a few of Russia’s major competitors in this decade. The U.S. offers contractual flexibility to buyers. Qatar could very well compete with Russia on cost. East Africa could also compete with Russia in growing markets in South Asia (especially India) and Northeast Asia due to its advantageous geographical position.

The war in Ukraine has opened a new chapter for global energy markets, for exporters and importers alike. Russia’s energy strategy and doctrine will have to be rewritten accordingly.

Facts & Figures: Energy in Russia

- Global economic growth is projected to slow from an estimated 6.1% in 2021 to 3.6% in 2022 and 2023. This is 0.8 and 0.2 percentage points lower for 2022 and 2023 than projected in January (IMF, World Economic Outlook April 2022)

- Russia is the 11th-largest economy in the world, but its GDP is only 7% of that of the U.S. – the largest economy in the world

- Russia’s technically recoverable shale oil resources are estimated to be 74.6 billion barrels, compared to 78.2 billion barrels in the U.S.

- Revenues from oil and gas accounted for 45% of Russia’s federal budget in 2021

- The bulk of Russia’s oil and gas fields are concentrated in Western and Eastern Siberia

- Rosneft and Gazprom, both state-owned, are the largest oil and gas producers in Russia, respectively

- In 2021, Russia accounted for approximately 8% of global LNG supply

Related Analysis

“Sanctions and the Economic Consequences of Higher Oil Prices“, Christof Rühl, Apr 2022

“Energy Markets and the Design of Sanctions on Russia“, Christof Rühl, Mar 2022