Dr Carole Nakhle

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent shockwaves across the world, especially in Europe. In energy markets, customers and households have been exposed to rapidly escalating prices at a critical time when the economy was only recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, the impact of the crisis on prices is only one side of the story and will likely be resolved by market mechanisms over time. The bigger and more lasting effect is the tectonic shift triggered in global trade, investment decisions and policy changes.

Energy security has always been an important pillar of the EU’s energy policy, but it has received varying attention over the years. In times of scarcity (even if only perceived), it acquires a great sense of urgency, but then it goes on the back burner when supplies are plentiful and prices low. Today, the issue is center stage once again. Everyone is closely watching Russian energy supplies to Europe, gauging the threats and hoping to weaken this political leverage. As described by European Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson: “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has aggravated the security of supply situation.”

Determination

Europeans had long been concerned that Russia was using its energy trade for political goals. The current crisis has confirmed these fears; Europe has not been able to sanction Russian energy exports because of its significant dependence. Since 2013, all EU member states have been net importers of energy, with Russia as the leading supplier of the main primary energy commodities – natural gas, crude oil and hard coal.

The invasion of Ukraine was one step too far for the international community. But the EU’s indecisiveness in imposing sanctions on Russia’s energy trade was criticized by many commentators. The EU has therefore announced its intention to phase out dependence on Russian fossil fuels well before 2030. “The new geopolitical and energy market reality requires us to drastically accelerate the clean energy transition and increase Europe’s energy independence from unreliable suppliers and volatile fossil fuels,” the European Commission declared in early March.

Several questions arise from this statement, chief among them where those supplies will come from. The focus has been largely limited to replacing Russian oil, coal and gas. However, as it has been widely recognized, a quick switch to other sources of fossil fuels is neither practical nor simple. Additional supplies need to be sourced to fill the massive gap left by the loss of not only the largest exporter of fossil fuels to the continent but also one of the lowest-cost suppliers. A fraction of those is readily available, but for more substantial volumes, investment is needed, especially given the competition from other regions and consumers.

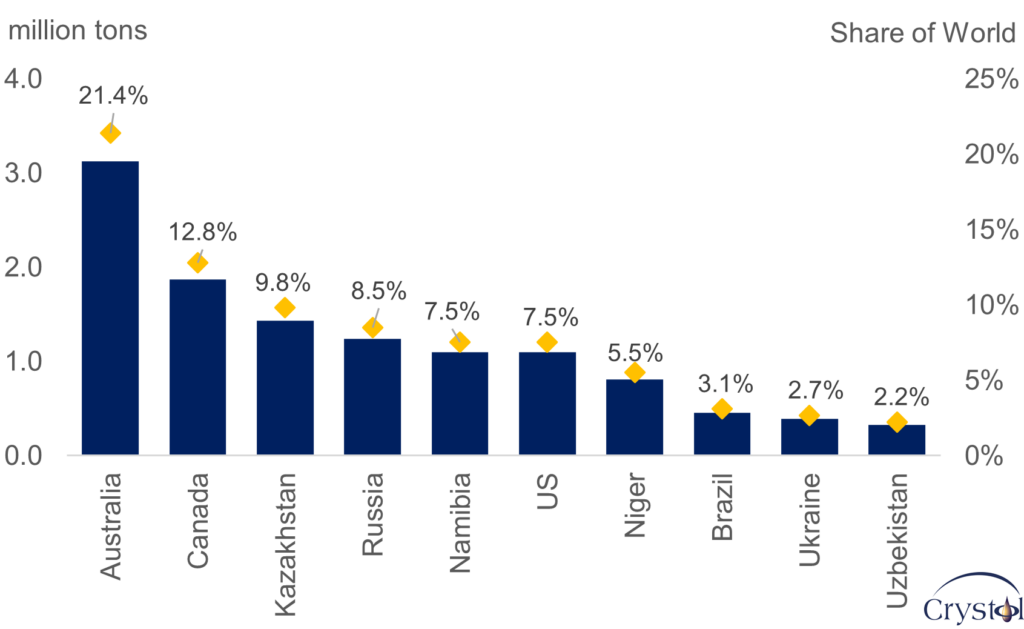

Uranium resources by country

Data Source: IAEA

Missing fuel

Investment is needed not only in oil, coal and gas but also in alternative sources of energy, including renewable energy and nuclear power. The International Energy Agency (IEA) acknowledges the role nuclear power can play in reducing the EU’s dependence on Russia’s gas supplies and recommends maximizing generation from the Union’s largest source of low-emissions electricity. Besides, in most 1.5 degrees Celsius pathways considered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the share of nuclear power in electricity generation is modeled to increase. Nuclear energy is also seen as more compatible with the EU’s climate change targets than fossil fuels.

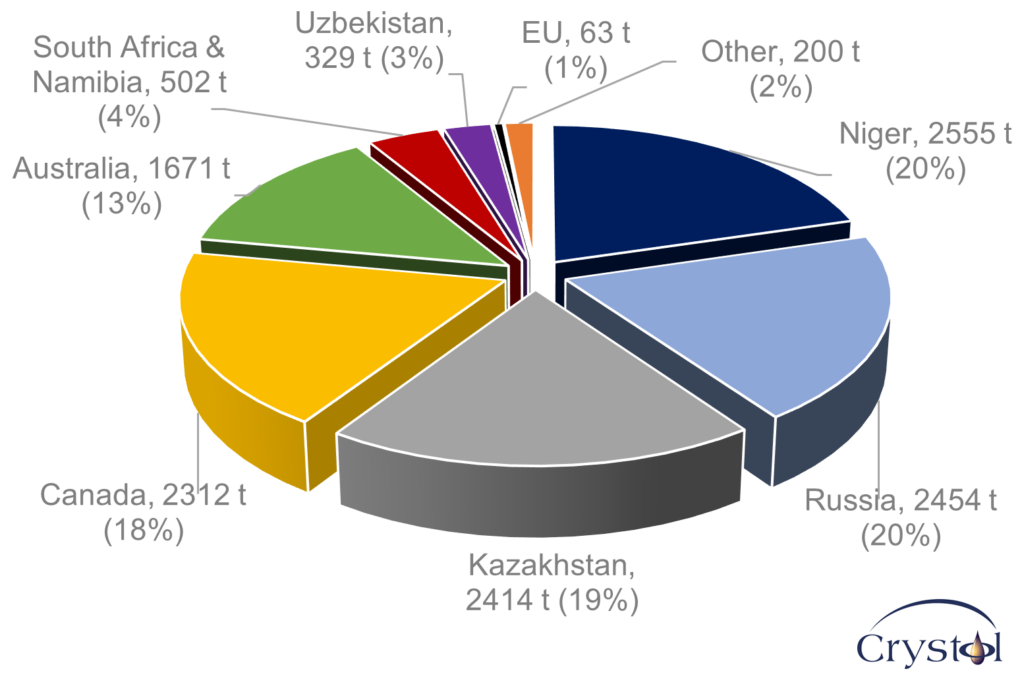

Nuclear power meets around 25 percent of the EU’s electricity generation, though in countries like France it is more than 66 percent. Russia is the second-largest exporter of uranium to the EU, providing 20.2 percent of the Union’s needs, after Niger (20.3 percent). Somehow, this aspect of Russia’s trade with the EU has been widely omitted from the bloc’s official statements in response to the ongoing crisis. This could partly be because only 13 members of the Union use nuclear power, but some of them export nuclear-generated electricity to neighboring countries.

More importantly, nuclear energy is a controversial issue. In February, the European Commission unveiled its taxonomy for environmentally sustainable activities and extended this categorization to nuclear energy if countries can prove they can safely dispose of the waste. Such a classification, however, created a backlash, as opponents of nuclear power argue that it has the potential to “do significant harm,” which precludes securing the EU’s green label.

Sooner or later, the EU will come under pressure to revisit its dependence on Russian uranium. At a press briefing in March this year, Swedish Minister for Energy and Digital Development Khashayar Farmanbar stated that the Swedish government “wants to see two concrete changes to the European energy supply. Firstly, the EU needs to stop depending on Russian gas. Secondly, the EU member states need to stop importing nuclear fuel from Russia.”

Phasing out Russian uranium while safeguarding (or even expanding) domestic nuclear power would mean increasing reliance on other countries. However, the EU needs to carefully assess the risk that comes with relying on other suppliers. Kazakhstan, for instance, has the potential to fill some of the gaps created by the loss of Russian uranium. However, the EU would have to weigh the geopolitical risks. Kazakhstan faces Russian claims to some of its northern territories and depends on Moscow and Beijing to export its resources.

Wider perspective

The EU’s security of supply is clearly laid out in the 2015 European Energy Security Strategy: “EU prosperity and security hinges on a stable and abundant supply of energy” – a definition that continues to apply, although it tends to single out natural gas as the main fuel of concern. The IEA uses a more comprehensive phrasing: “reliable, affordable access to all fuels and energy sources,” especially as the energy transition has expanded the scope of what constitutes energy security. This ought to be the definition that the EU adopts and pursues.

EU uranium imports by country, 2020 (tons)

Data Source: Euratom

One study further expands the concept and argues that energy security must extend beyond traditional concerns like the security of fossil fuel supplies. “Energy security – equitably providing available, affordable, reliable, efficient, environmentally benign, proactively governed and socially acceptable energy services to end-users – is inextricably tied up both with traditional conceptions of national security and with emerging concepts of human rights and individual security,” the document concludes.

This definition, if fully adopted, would cause serious problems for the EU, as some of the Union’s key energy exporters, particularly in developing economies, do not score well on many of those aspects. Such goals may also seem unachievable in the midst of the current crisis, but they should give the EU a sense of direction when reaching out for new energy supplies and committing to long-term purchases.

Related Analysis

“The potential of small nuclear reactors“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Mar 2022

“Times letters: High energy prices and the switch to net zero“, Lord Howell, Dec 2021

Related Comments

“Will the gas crisis in Europe act in favour of nuclear energy?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2022