Dr Carole Nakhle

This report was written in conjunction with Roberto Ulivieri.

In 1907, a United States court observed in its ruling that “oil is wild and will run away if it finds an opening.” Such a basic yet powerful feature of oil explains why Russian oil, if forced to leave the market through one door, will find a way to return through another – either in its crude state or disguised in a refined product. As a result, much guesswork is involved in estimating how many barrels global oil markets could lose if Russian supplies are curtailed, whether through embargoes or sanctions.

Being a liquid, oil is much easier to store and transport than natural gas (or, in fact, any other nonliquid fuel). Consequently, oil markets offer greater flexibility. For a buyer, the access to ports and oil depots automatically grants access to a global market where nearly three-quarters of the oil produced – a staggering 65 million barrels a day (mb/d) – change ownership across countries and regions while involving a myriad of traders the world over.

In contrast, in the natural gas market, infrastructure often links a buyer and a seller who become interdependent for being unable to either buy from somewhere else or sell somewhere else. That technical constraint explains why only a quarter of the gas produced is traded internationally.

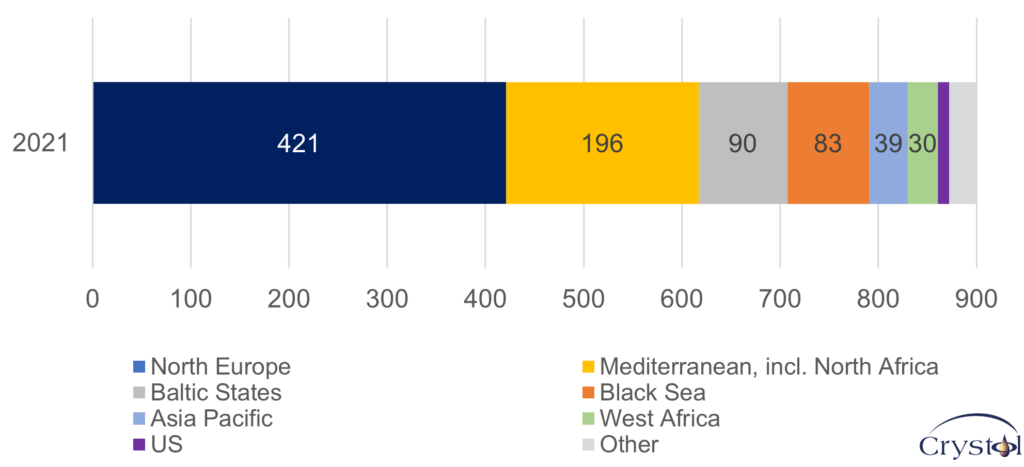

Russia’s diesel exports 2021, '000 barrels per day

Europe’s dependence

Russia’s importance to global and European oil markets stems from its role as a major exporter of both crude oil and oil refined products, primarily diesel.

In 2021, Russia produced 10.8 mb/d of oil (around 11 percent of the world total), out of which nearly 5 mb/d was sold abroad. About 1.5 mb/d was exported via pipeline to the Far East (China and the Pacific region), and around 0.5 mb/d typically supplies refineries in Belarus and Kazakhstan. Approximately 0.4 mb/d are produced in the Russian Far East and traded in the Pacific region.

Most of the remainder, approximately 2.5 mb/d, ended up in Europe, where European refineries largely processed it to make oil products, including diesel for local consumption. Additionally, Russia exports close to 3 mb/d of refined and semi-refined products (including 1 mb/d diesel), most of which stay in Europe. The rest is sent to the U.S. and Asia via Europe.

If Europe imposes sanctions on Russia’s oil exports, one might therefore expect Russia to lose access to its most important market and logistics and suffer economic consequences. This reasoning, though, does not consider the dynamics of the global oil trade.

Unrealistic expectations

For a successful sanctions scenario to materialize, all major oil consumers would need to reject Russian oil. However, among those who are unlikely to go down that route happen to be the world’s biggest net oil importers, namely China and India; they alone are large enough to absorb the entirety of Russian exports. In fact, some Indian refiners have bought more cargoes carrying Russian oil since the invasion of Ukraine began and have been open about their intention to benefit from the opportunity to buy at below-market prices. Chinese trader Unipec reportedly traded Urals to China in February. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov bluntly stated that Russia would be able to redirect crude oil not taken by European buyers to the Asia-Pacific market.

More recently, CNOOC, Sinopec and Sinochem, three large Chinese state-owned refiners, have announced their intention to stop buying Russian crude. These companies jointly operate approximately 7 mb/d of refining capacity, but there is another 11 mb/d of capacity in China that is not operated by these companies.

Not all buyers share the same standard of ethics. Even without sanctions, many buyers (primarily Western-based, but also some Asian) have shied away from Russian crude for various reasons that include the difficulty of financing transactions, arranging the shipping and, above all, reputational risk.

Shell, for instance, faced a notable backlash after buying a cargo of Russian oil at the $27.85 per barrel (/bbl) discount to Brent – the industry’s commonly used benchmark against which many other crudes are assessed. ExxonMobil had to publicly clarify that a cargo received at its Fawley refinery was Kazakhstan crude shipped via Russia. Because of the widespread self-sanctioning, Urals, the main Russian export grade, sold at a discount. In January it was trading at $1/bbl below Brent. By March, it had fallen to below $30/bbl.

This is surely bad news for Russia. However, it is exactly that discount that will attract other buyers. Any refiner willing to process Urals crude purchased at current prices is certain to make its highest-ever margin. Supply chains will develop outside the sanction perimeter and Russian crude prices will gradually find a new equilibrium, perhaps at more moderate discounts. The outcome will depend on what share of the global market remains accessible to Russia, which will determine who has pricing power.

How, one may ask, has the tool of sanctioning oil exports largely worked against Iran, stunting its economic growth and curbing its regime’s militarist ambitions, but is expected to prove less effective against Russia? The short answer is that Iran is a much smaller oil exporter, the sanctions have been imposed on it for decades. Iran is not a significant exporter of refined products; at one point, it was actually a large importer of gasoline.

Technically, refineries are configured to take specific types of crude. Urals is a medium gravity crude, and European refineries will find it challenging to replace it. The most favorable options from the standpoint of logistics and pricing would be light crude. Like-for-like replacement would be available from the Middle East. However, Middle Eastern crude has historically fetched higher prices in the Asian market precisely because the European market used to be supplied by Russia. It will be interesting to see how the market allocates pricing power between European refiners with few options to replace Russian crude and sellers with their highest value markets flooded by cheap Russian crude. The price of European crude will most likely rise relative to the rest of the world.

Opportunities for third parties

The supply gap resulting from the loss of Russian diesel in Europe would have to be filled, most likely by supplies from the Middle East and Asia. For example, Total has announced it will stop buying diesel from Russia and replace it with diesel sourced from its share of the SATORP refinery in Saudi Arabia. This replacement, however, will not come for free. European diesel prices will have to increase relative to other markets to cover higher transportation costs and make such a trade viable.

Furthermore, Russian refineries can still sell diesel at very competitive prices, especially since they are subsidized. At current crude market prices, the margin for a European refinery could go negative by several dollars, while a Russian refinery can still sell at a profit.

In this case, a country like India (which exports 25-30 percent of its diesel production, and around 0.3 mb/d of it goes to Europe), can import discounted Russian diesel for local consumption and export their own diesel to Europe. India and China are notable for their size, but many other countries could do the same. Europe would pull more supplies from the global market and Russian diesel displaced from Europe would flow to other world markets to fill the gap.

Scenarios

Of course, Russia will incur some pain even in the currently imperfect world of sanctions. While it can keep selling oil and refined products, it would have to price them as needed to achieve a larger share of a smaller accessible market and to overcome any resistance related to the risk of dealing with it. It will have to penetrate markets that are further away and are more costly to access. The discounting will therefore stay at some level.

But Europe, too, will have to accept the inconvenient truth of facing higher prices – the result of severing relationships with a low-cost supplier of crude and products.

As long as there is no global coordinated effort to sanction Russian exports of crude oil and oil products, a partial sanctions regime would lead merely to a global rearrangement of trade flows with financial losses on both sides. This would produce some winners among those who will be there to capture the commercial opportunities.

Related Analysis

“Sanctions and the Economic Consequences of Higher Oil Prices“, Christof Rühl, Apr 2022

“Energy Markets and the Design of Sanctions on Russia“, Christof Rühl, Mar 2022

“No endgame for Ukraine“, Christof Rühl, Feb 2022

Related Comments

“Is Moscow turning to Asia?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2022

“Oil Prices and EU Energy Crisis“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2022

“Putin demands gas exports to be paid in rubles, and US SPR release“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2022

“The EU’s 4th round of sanctions on Russia“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Mar 2022

“Can Europe completely cut its reliance on Russian energy supplies?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Mar 2022