Lord David Howell

In the battle to curb global climate change good intentions are everywhere. A major new U.N. Climate Change Conference is coming up (COP 26 in Glasgow this autumn, chaired by the U.K. and Italy), and U.S. President Joe Biden has vowed to bring the United States back into the Paris accord.

But what happens when good intentions and hard reality become so far apart that they cease to connect? That is just the situation that lies a year or two ahead on the climate change issue.

While nations and political leaders around the world are now strongly committed to targets for reducing carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases to zero, while many nations are dead set on virtuous green agendas and making real progress in cleaning up their energy production patterns, and while investment in renewables, especially wind and solar, will be roaring ahead, the global emissions numbers will be receiving little notice.

Instead, after the one-year respite caused by COVID-19, they will be staying stubbornly high, just as they were before the pandemic pushed down world energy demand for a while. In the 10 years up to 2019, global emissions rose 16%, taking them ever further away from the Paris Agreement goals. To get back on to the Paris path (world temperature no more than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels — and ideally 1.5 degrees), requiring a carbon neutral world by 2050, emissions would have to be falling substantially by at least 7.6% a year for at least the next 10 years.

This is just not going to happen unless some realities are faced. As the world economy bounces back, emissions will at best be plateauing and probably still be climbing. This will be despite strong pledges all around at the forthcoming conference, and despite considerable success in reducing emissions and advancing the green agenda, in countries such as the U.K. itself.

Renewable power costs may be falling dramatically; oil and gas investments are being boycotted; electric vehicles heavily encouraged; and energy bills for consumers being kept sky high (although with growing popular unrest). Yet annual global emissions keep adding to the global greenhouse around us, when it is drastic subtraction that is needed.

None of this may be welcome or popular news at the present time. But the hard facts are rolling down the road toward us, and soon they will have to be faced.

This means first and foremost, recognizing where the real drivers of persistently high global emissions lie, and where the practical chances of significant cuts lie. And the answer is not a mystery at all.

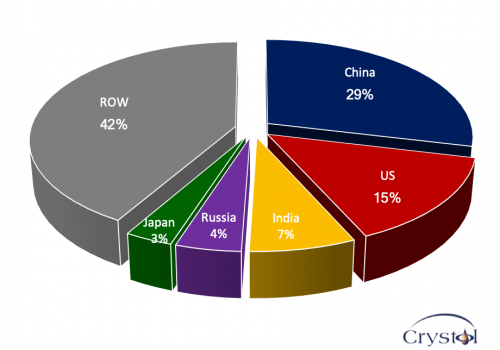

The biggest single world source of carbon emissions (46%) is coal burning, and the biggest coal-burning countries are China, India, Russia and the U.S. itself. Unless this figure is drastically cut back, all other “achievements” around the planet, however commendable — such as declining emissions trends in the U.K., Germany, Mexico, France and Japan — will simply be overwhelmed.

Share of Global CO2 Emissions by Country, 2019

Data Source: BP Statistical Review, 2020

So that is where the best minds, the best brains, the best science and technology and the most national and international efforts should be concentrated. The rest of the green agenda, now being pursued in many advanced economies may feel good and make environmental sense for the lucky citizens in these countries, but the impact is marginal in the climate battle and will remain so.

What therefore to do to tackle this real core of the global problem?

There is plenty of talk about closing coal-fire electricity down entirely, and in some European countries, such as the U.K., it is happening, although not in Germany and certainly not in Poland. But elsewhere it is only talk. Thirty-nine percent of Indian electricity still comes from coal and more stations are being constructed. In China, coal-fueled electric power still dominates (at more than 50%), despite that country’s vast renewables and nuclear expansion. Dozens more coal-fired stations are still being built across Asia.

These are mostly in countries that are hungry for more energy, with significant proportions of their populations without regular power supplies at all, and desperate for affordable energy to escape poverty. Their basic industries, like steel and cement, are vital to their future.

Nothing is going to halt the oncoming surge for more power, and from the cheapest source, which is coal by far. Nothing is going to halt their demand for greatly increased transport, whether gasoline or electric. Nothing in the way of examples from the West, or pledges, or lectures, is going to halt the burning of coal and the rising emissions that go with it.

The answer is not just to wring hands and pass resolutions deploring coal burning. That may be the present fashion but it will solve nothing. A way has to be found to burn coal cleanly, and that way does already exist. It can be done. The technologies for capturing, reusing or storing the carbon emitted are there. But the requirement is to get the cost of the process down, which demands massive further research and innovation on a Marshall Plan or Manhattan Project scale.

No amount of virtuosity on the part of the richer world in restricted flying, eating less meat, cycling instead of driving, solar paneling, planting more trees, higher fuel taxes or shutting down carbon intensive industries (and jobs) — however desirable some of these things are in themselves — will tackle the climate threat seriously or effectively.

None of these projects, programs and commitments will cut the large swathes out of annual emissions needed to avoid the coming danger point. Only a direct assault from every angle on the capture, piping away and re-usage of carbon from tens of thousands of coal plants across scores of Asian countries will check greenhouse Earth continuing to heat up remorselessly.

Courageous Western leaders must now explain and admit it, and start shifting their priorities and resources accordingly, to put this essential goal first and above all in the climate battle. But how much of that kind of courage is there around?

The article was first published by the Japan Times

Lord Howell was also quoted in Arab News Japan and South China Morning Post

Related Comments

“Energy Transition Implications on Exploration and Exploitation of Petroleum Resources“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Dec 2020

“Oil in the energy transition age“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Mar 2020