Dr Carole Nakhle

In July, the United States and the European Union announced a trade deal that de-escalated growing tensions over tariffs and reinforced transatlantic economic ties. Under the deal, the U.S. agreed to reduce its proposed tariff on EU imports from 30 percent to 15 percent – a single, all-inclusive ceiling on nearly all EU exports currently subject to reciprocal tariffs. In return, the EU committed to significantly deepen its economic engagement with the U.S., including $600 billion in new investments by 2028, in addition to the more than $100 billion that European companies already invest in America every year. The EU will also lift major trade barriers, including eliminating all tariffs on U.S. industrial exports.

Energy emerged as a central pillar of the deal: The EU will notably expand its purchases of U.S. oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), nuclear fuel and related services, increasing annual imports from around $90-100 billion in 2024 to $250 billion annually over the next three years. This brings the total value of EU energy imports from the U.S. to a projected $750 billion by 2028 – the end of President Donald Trump’s current term in office.

Both sides have framed the agreement as a political and economic landmark. For Washington, it promises to generate tens of billions of dollars in annual revenue and reduce the U.S. trade deficit with Europe, allowing American businesses to increase their exports to the EU and expand business opportunities there. For Brussels, it offers stability and predictability, shielding European businesses and consumers from a full-blown trade war.

Energy lies at the core of the deal’s strategic purpose, reducing Europe’s dependence on “adversarial suppliers,” to quote the White House, and reinforcing energy security. The EU made that intention explicit, stating that the agreement will help replace Russian energy in European markets.

The agreement has not been universally welcomed. Critics have argued that the import targets are “unrealistic” and “delusional,” and that they exceed U.S. export capacity and clash with the EU’s declining gas demand and climate change agenda. Others caution that Europe may be replacing one dependency for another, shifting from overreliance on Russian energy to reliance on the U.S.

These concerns are legitimate. The long-term sustainability of the agreement remains uncertain, particularly if a future U.S. administration reverses course, as the Biden administration previously did by pausing new LNG export approvals. Nonetheless, overall, the deal provides a degree of certainty and stability that benefits both sides, even though its terms are not set in stone and the final outcome will be dictated by market trends.

For European consumers, it provides access to large energy supplies that are less prone to geopolitical coercion – a sharp contrast to past exposure to Russian energy. For American producers, it improves demand visibility, which is important to support long-term investment.

Most importantly, the deal sends a strategic message that goes well beyond the numbers. Transatlantic trade and energy policy are increasingly aligned in countering Russian influence and promoting supply diversification, and the U.S. has firmly positioned itself as Russia’s main energy rival in Europe.

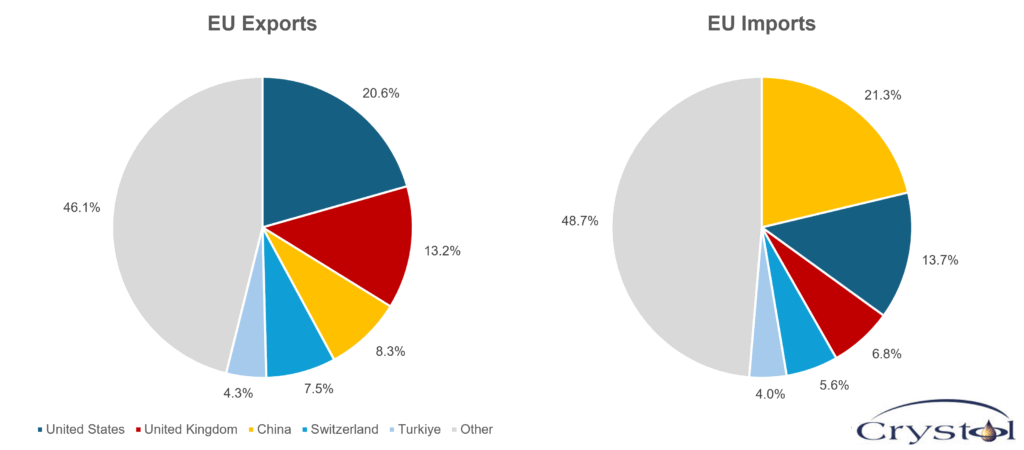

EU trade in 2024

Source: Council of the European Union

U.S. impact on European gas trade

America has long been one of the EU’s most important economic partners; its top export destination and second-largest source of imports after China. The 2008 shale revolution transformed the U.S. from a major importer into one of the world’s leading oil and gas producers and exporters. This shift had far-reaching effects on global energy markets, particularly in Europe, even before U.S. LNG exports began.

Prior to the shale boom, the U.S. and EU competed for global gas supplies, but Europe relied heavily on Russian energy. As U.S. domestic production surged, its demand for imports declined. LNG cargoes originally destined for North America were diverted to Europe, increasing global supply and exerting downward pressure on gas prices.

This influx of spot-market LNG highlighted the price gap between flexible contracts and Europe’s oil-indexed, long-term agreements with Russia. European utilities bound by long-term Russian contracts faced higher costs as oil prices stayed elevated, prompting pressure on Gazprom to renegotiate terms. To defend its market share, Gazprom began offering more flexible pricing, including spot-linked sales. The episode marked a turning point in Europe’s gas pricing structure and further strained its energy relationship with Moscow. In 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin criticized Europe’s shift away from long-term contracts in favor of the spot market, calling it a “mistake.”

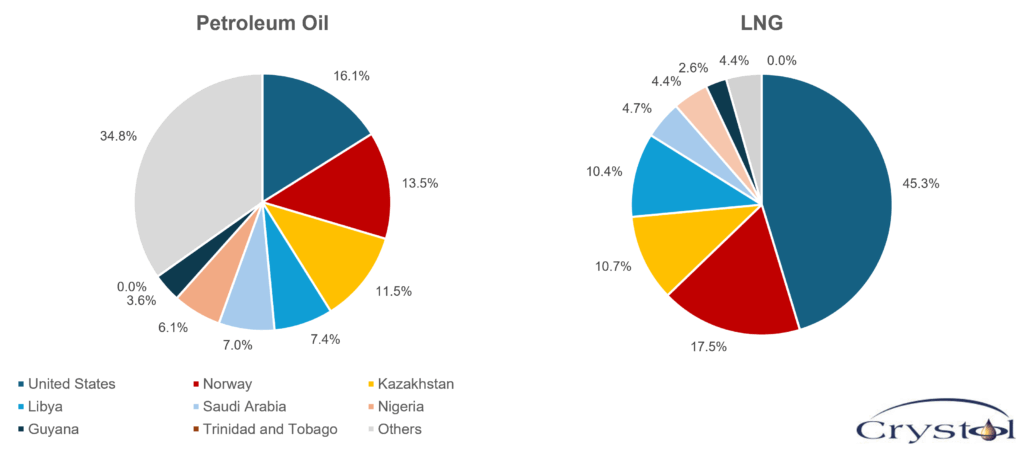

By the time U.S. LNG exports began, the market had already felt the disruptive impact of the shale revolution. In 2022, the U.S. became the world’s top LNG exporter, overtaking Qatar and Australia – a position it is expected to maintain as new export capacity comes online by 2028. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, U.S. LNG quickly filled the gap left by Russian supply, driven by soaring prices.

Unforeseen increase in U.S. energy exports

Long before the Ukraine crisis, Washington had been laying the institutional and commercial foundations for deepening its energy ties with Europe. The July U.S.-EU trade deal amplifies a strategy that has been steadily evolving for nearly a decade.

A key turning point came in July 2018, when President Trump and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker launched a new phase of U.S.-EU strategic energy cooperation. The goal was clear: to boost LNG imports from the U.S. to enhance Europe’s energy security and reduce its reliance on Russian gas. “They will be a massive buyer, and they will be able to diversify their energy supply. … The EU will build more terminals to import liquefied natural gas from the U.S. This is also a message for others,” President Trump said then. He also openly criticized Germany’s support for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, warning it would deepen Russia’s dominance over European gas markets.

At the time, U.S. LNG exports to the EU stood at just 4 billion cubic meters (bcm), with modest expectations that volumes would double to 8 bcm by 2022. What followed exceeded all projections: by 2022, LNG exports from America to the EU reached 55 bcm, or 72 bcm if the United Kingdom and Turkiye are included.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 accelerated the trend. The following month, then President Joe Biden and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen launched a Joint Task Force on Energy Security to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels. As part of the agreement, the U.S. pledged to “strive to ensure” at least 15 bcm of additional LNG deliveries to the EU in 2022, with further increases expected in subsequent years. In parallel, the commission committed to working with member states to ensure demand for up to 50 bcm per year of additional U.S. LNG through 2030, potentially pushing total U.S. LNG volumes to Europe above 120 bcm per year by the end of the decade.

These initiatives have been pivotal in supporting the EU’s ambition to eliminate Russian energy imports entirely by 2027.

EU energy imports

Source: Eurostat

Questionable numbers underlying targets

According to the European Commission, the projected $250 billion per year over the next three years reflects the estimated average value of EU energy imports from the U.S. The commission says the figure is based on robust assessments that considered several factors: current import volumes, expected increases in oil, gas, and nuclear fuel imports as part of the shift away from Russian energy, and major U.S. energy technology investments, services and exports to the EU – especially in the nuclear sector, including conventional and small modular reactors (SMRs).

Many have questioned the credibility of the figures. When viewed against current market prices, critics argue that meeting this target would require the EU to import up to 930 bcm of LNG, more than three times its total gas consumption in 2024, which stood just below 300 bcm. While the EU is an important market for gas, the import needs stem from a decline in domestic production, and not because demand is growing rapidly, as is the case in Asia. Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Europe’s natural gas market showed limited growth. EU gas demand had peaked in 2010 and by 2022 was 19 percent lower.

Meanwhile, remaining Russian gas imports (both pipeline gas and LNG) to the EU for this year are expected to average around 23 bcm. This does not create sufficient demand to absorb the additional planned imports from the U.S.

Observers have also questioned the reliability of the supply. The physical export capacity of the U.S. is currently around 117 million metric tons per year, equivalent to around 150 bcm of gas. While this may expand to 212 million tons per year (roughly 272 bcm) by 2028, that projection depends on the rapid completion of several projects that are still awaiting final investment decisions.

In short, the math does not add up, leading some analysts to conclude that the EU’s energy spending pledge is unlikely to materialize.

To complicate matters further, commercial, not political, decisions determine market needs. A mix of private and state-owned companies import gas in the EU. The European Commission can aggregate demand for LNG to negotiate better terms through its joint purchasing of gas initiative, which it established in 2022 to improve the EU’s purchase position vis-a-vis non-Russian pipeline gas and LNG imports. However, the commission cannot force companies to buy the fuel.

Then comes the question of sustaining demand for, and purchases of, fossil fuels while upholding the EU’s climate commitments. The European Environmental Bureau (EEB), the continent’s largest network of environmental NGOs, warns that the centerpiece of the deal is fundamentally incompatible with the EU’s 2030 climate targets. The EU has rejected the accusation, stating that it still aims to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

Import dependency concerns

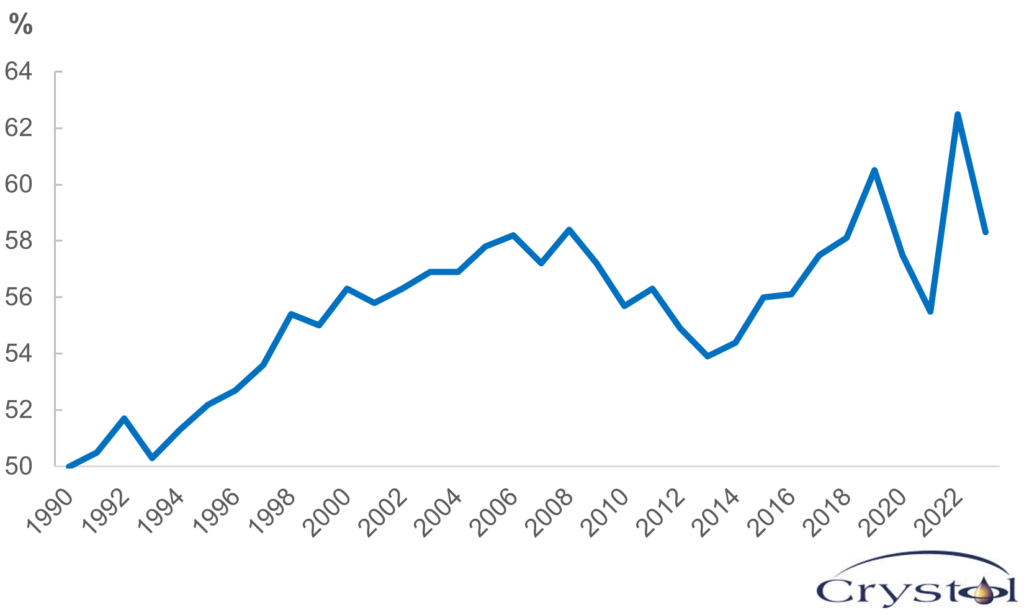

The EU is likely to remain reliant on energy imports to meet a significant share of its domestic needs over the coming decade – a vulnerability with both economic and security implications, as highlighted by a study from the U.S. Federal Reserve. In that context, securing supplies from a trusted ally such as the U.S. can be seen as an important pillar of Europe’s energy security. That strategy has already proven effective: Although gas prices spiked in 2022, the crisis was relatively short-lived as LNG, particularly from the U.S., helped fill the gap.

However, if the EU is to meet its spending commitments under the July trade deal with the U.S., it could risk undermining the very diversification efforts it has worked hard to achieve. Import dependency reached its highest level since 1990 in 2022. Since then, the EU has taken steps to lessen its reliance on external suppliers. In its energy security strategy, the commission states: “A key part of ensuring secure and affordable supplies of energy to Europeans involves diversifying supply routes. This includes identifying and building new routes that decrease the dependence of EU countries on a single supplier of natural gas and other energy resources.”

European energy import dependency ratio

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve

The current deal, however, risks making the EU overly reliant on a single supplier, even one as reliable as the U.S. Political dynamics can shift quickly. The same caution applies to the U.S. If it were to deliver the full volume of supplies committed under the deal, it would increase its exposure to the European market and its evolving policies, particularly those tied to climate change and decarbonization.

To address such concerns, the European Commission has proposed a dedicated framework – AggregateEU – to collect demand from EU buyers and match it with competitive U.S. LNG supplies for the period 2025 to 2050. The mechanism aims to balance strategic alignment with market flexibility, ensuring that energy cooperation remains resilient in the face of political and economic shifts.

Scenarios

The deal should be viewed in context rather than through headline figures alone. Many details are still unclear, and the $750 billion target by 2028 includes a mix of energy imports – not just LNG. Moreover, converting spending targets into actual volumes depends heavily on price assumptions, and market conditions could change significantly over the coming years.

As the European Commission has clarified, while indicative projections exist, the final breakdown between oil, LNG and nuclear fuel will be contingent on several variables, including commodity prices, exchange rates and investment decisions by private companies. Ultimately, outcomes will be shaped by commercial transactions, not political commitments.

Importantly, the deal is non-binding and imposes no legal obligations on either side. Even if the targets are not met, the current tariff framework will expire with President Trump’s term in 2028, leaving Washington without leverage to retaliate.

The July U.S.-EU trade deal is best viewed not as a rigid contract, but as a political signal – one that builds on more than a decade of increasingly intertwined energy and trade interests. While the numbers may raise eyebrows, the message is clear: the U.S. and Europe are strategically aligned in countering Russia’s influence, at least in energy trade. What happens next will hinge on both market fundamentals and political continuity.

Most likely: Strategic alignment holds

Despite doubts over the numbers, this scenario reflects what is already underway: U.S. LNG capacity is expanding, EU demand for reliable non-Russian energy remains and commercial relationships are driving long-term contracts. The deal amplifies a natural, market-supported shift already in motion. Even if targets fall short, all signs point to closer cooperation, reinforced by shared strategic goals and a decade of institutional groundwork.

Less likely: Political or market disruptions derail progress

In this less likely, but still plausible, scenario, political changes in the U.S. or accelerated EU decarbonization efforts undermine the deal. U.S. export policies could tighten, or European buyers may not follow through due to falling gas demand. Trust could erode, and the momentum built since 2018 may stall.

Related Analysis

“U.S. shale oil and gas: From independence to dominance“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2024

“The UK attempts to become a ‘clean energy superpower’”, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2024

“Energy security: Perceptions versus realities“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2024

Related Comments

“Experts warn of trade tensions on oil demand“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Apr 2025

“Why London is a great place for energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Feb 2025