Dr Carole Nakhle

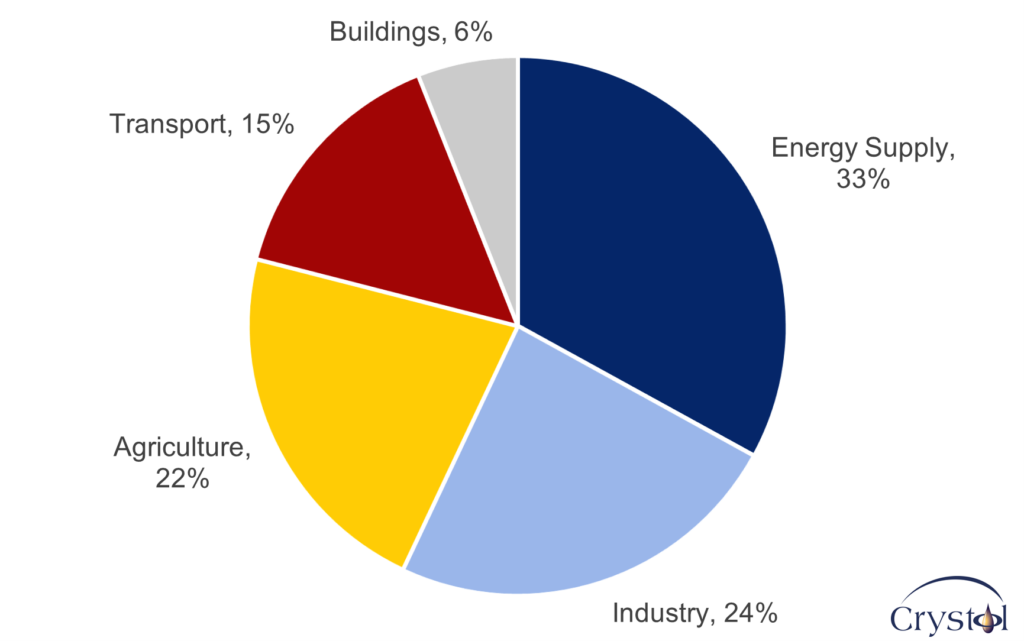

Globally, the transport sector is not the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the main culprit behind climate change. However, it is widely considered the most difficult sector to decarbonize. “Without aggressive and sustained mitigation policies being implemented, transport emissions could increase at a faster rate than emissions from the other energy end-use sectors,” the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned.

The sector has uniquely relied on a single fuel, petroleum, which supplies 95 percent of the total energy used by world transport. Road transport, both passenger and freight, is responsible for nearly three-quarters of all transport emissions. Continued growth in these activities could outweigh all climate change mitigation measures, the IPCC has argued.

It is no wonder that at COP26, the United Nations’ 2021 climate change conference in Scotland, the parties agreed to accelerate the transition to zero-emission vehicles to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. Their aim is to have all global sales of new cars and vans zero-emission by 2040, and by 2035 or sooner in leading markets.

Currently, electric vehicles (EVs) powered by low-emission electricity offer the greatest potential to decarbonize land-based transport. Their rapid deployment will also have the biggest detrimental impact on oil demand. Such a shift would mark the second time in history when electrification existentially threatens the oil industry, after the invention of the electric light bulb two centuries ago.

Greenhouse gas emissions by sector

Data Source: IPCC

Much of the debate over the future of the transport sector and EVs has focused on technical matters, like setting targets to reduce carbon emissions. But more qualitative questions are capturing growing attention: How will the adoption of EVs affect the billions worldwide who cannot afford them? And what would the end of oil mean for the developing countries whose economies depend on it? Overlooking issues of equity and justice in the energy transition risks worsening the global divide between rich and poor, and stoking new resistance to climate efforts in the developing world.

Existential threat

Oil entered the transport sector by chance. The early use of this fossil fuel was primarily for lighting. When Thomas Edison developed the first practical electric incandescent lamp, the oil industry of the era faced a serious threat: the oil lamp had become obsolete.

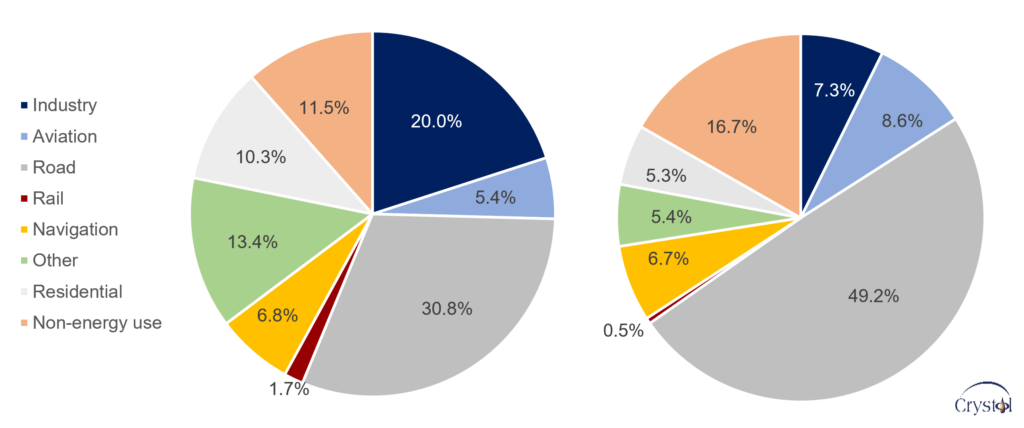

But just as one door closed, another, much bigger door opened: the development of the internal combustion engine, which gave oil a new lifeline that sustains it to this day. And while its use in sectors such as power generation has been declining since the first oil shock in 1973, its dominance of the transport sector – which captures more than 65 percent of total oil consumption – has been preserved.

The future of transport is thus central to the outlook for oil demand. Today, electrification is taking another run at the oil industry. If recent trends in EV sales continue and the relevant government plans materialise, the end of the oil age will be nearer than originally thought. The need for economic diversification in oil-dependent economies has accordingly become much more urgent.

Share of oil final consumption by sector, 1973 and 2019

Data Source: IEA

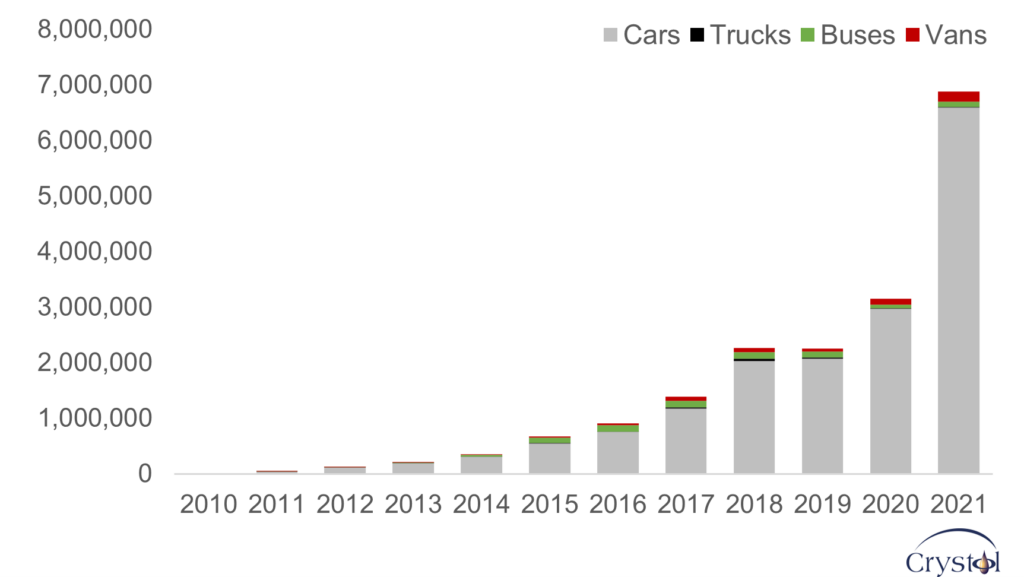

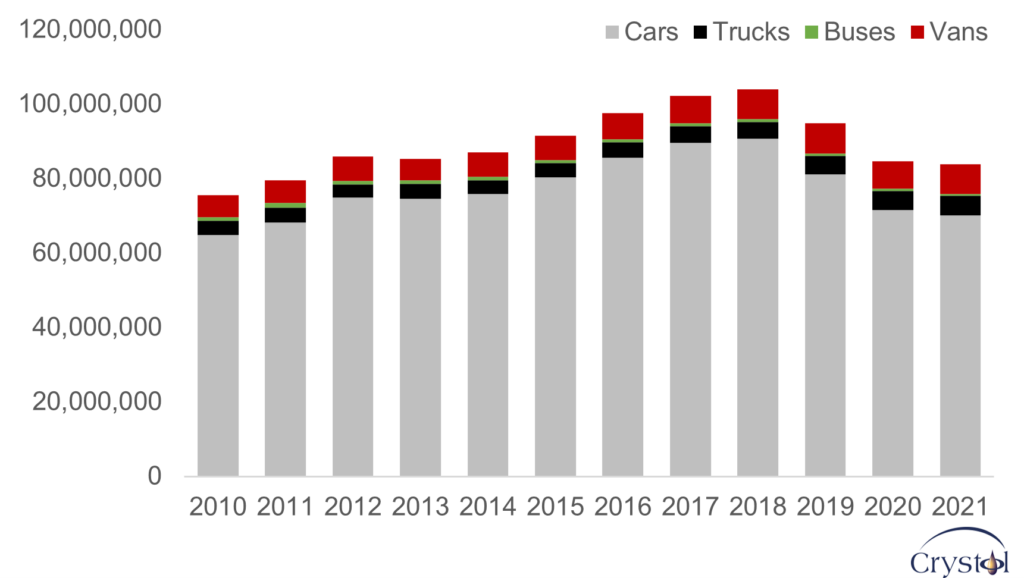

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), sales of EVs in 2021 doubled from the previous year to a new record of 6.6 million. While still a small absolute share – for comparison, global car sales grew to around 66.7 million automobiles in 2021, and today there are more than 1.4 billion cars worldwide – the growth rate has been staggering. The market share of EVs quadrupled in 2021 compared to 2019, and sales of EVs in the first quarter of 2022 were 75 percent more compared to the same period only a year ago.

The momentum is expected to hold, if not accelerate, particularly as governments continue to introduce measures favoring EVs – from subsidies and tax credits to a straightforward ban on the sale of new diesel/gasoline engine vehicles. In the United States, the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act provides EV tax credits of up to $7,500, in the hope of reaching a target set last year to have EVs comprise at least half of new vehicles by 2030. Norway announced the world’s most aggressive plan, with the sale of new petrol and diesel cars to be banned beginning in 2025.

Global electric vehicle sales

Data Source: IEA

Climate colonialism?

The zeal for electric vehicles is strongest in rich, developed economies. Among developing economies, China – which accounted for half of the growth in EV sales during 2021 – is the exception. Elsewhere, in countries outside the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, EV sales have been meager. In Brazil, India and Indonesia, for instance, EVs account for less than 0.5 percent of car sales, according to the IEA.

Affordability is a major barrier. For instance, in major markets, the price of a battery-powered EV tends to be 20-45 percent more expensive than a conventional car. Subsidies can help close the gap, but not all governments can sustain the generous handouts typical of those more endowed, especially with poorer nations facing more immediate issues of high food and energy prices. The majority of the world’s population today, which is concentrated in the developing world, cannot afford access to personal vehicles, or in many cases to any form of motorized transport.

Another crucial issue for the spread of EVs is access to electricity. A study by the Energy for Growth Hub estimates that a staggering 45 percent of the world’s population does not have access to reliable power. Unless that changes, the penetration of EVs will be significantly limited in such countries.

Global conventional vehicle sales

Data Source: IEA

Meanwhile, the metals and minerals needed to produce EVs and their batteries are mined in a number of developing countries, such as the cobalt-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo (one of the five poorest nations in the world). As the market for EVs expands, the mining of these minerals and metals will increase accordingly.

Setting aside the environmental footprint, these activities also pose socioeconomic and political risks in poorer countries, which often lack the institutions to manage a rush of new capital – the “resource curse” phenomenon. In many developing economies, resource wealth fails to deliver sustainable growth, in fact aggravating the poverty it promised to cure.

Unless the above three issues are tackled, the expansion of EVs may be aligned with the energy transition as defined by richer nations – but it will not be evenly distributed. This will likely foster resentment in poorer countries, with negative repercussions for the climate change agenda. Already, concepts such as “climate colonialism” and “green colonialism” have gained currency.

Just transition

A 2020 study described a “just energy transition” as one found in the “convergence of energy transitions and socioeconomic concerns.” Along similar lines, the Declaration on Zero Emissions Vehicles, struck at the COP26, recognizes “the importance of ensuring the transition to zero-emission vehicles is just and sustainable so that no community is left behind.”

Yet, under existing conditions outside the most developed nations, it remains unclear how the ambitious global targets for green vehicles can be achieved without leaving many communities behind.

A rapid transition to electric vehicles has widely been promoted without consideration for objectives like the UN Sustainable Development Goal 7, which refers to “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

As long as equity is not at the center of decarbonizing transport, EVs will remain a luxury beyond the reach of many living in poorer countries, who will greet the climate agenda with greater skepticism.

Facts & Figures

- In 2012, around 120,000 electric cars were sold worldwide. In 2021, more than that many are sold each week, with nearly 10 percent of global car sales now electric (IEA).

- Public spending on subsidies and incentives for EVs nearly doubled in 2021, to nearly $30 billion (IEA).

- Light-duty cars and trucks produce 40 percent of transportation CO2. Decarbonizing the sector will require that between 66 and 90 percent of passenger automobiles are zero-emission vehicles by 2050 (International Council on Clean Transportation).

- Transport is responsible for almost a quarter of European greenhouse gas emissions, with road transport by far the biggest emitter in the sector (European Commission).

- More vehicles were sold in China in 2021 (3.3 million) than in the entire world in 2020 (IEA).

- Transport demand is expected to more than double by 2050, compared to 2015 (International Transport Forum).

Related Analysis

“AI and the global energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2022

“Technology breakthroughs 2022: Energy storage“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jan 2022

“Time for realism in the climate battle“, Lord David Howell, Feb 2021

“The long road ahead for electric vehicles“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Nov 2017