Dr Carole Nakhle

Today, hardly any energy-related discussion can go without a mention of the energy transition. The focus is on greening the world’s primary energy and electricity mixes, which are currently dominated by fossil fuels – coal, oil and natural gas. Achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – whereby the amount of such emissions taken out of the atmosphere equals the amount we put in – is also gaining momentum as a desirable goal. Energy systems, infrastructure and related policies are undergoing a massive transformation to save the planet from further warming, blamed mainly on fossil fuels.

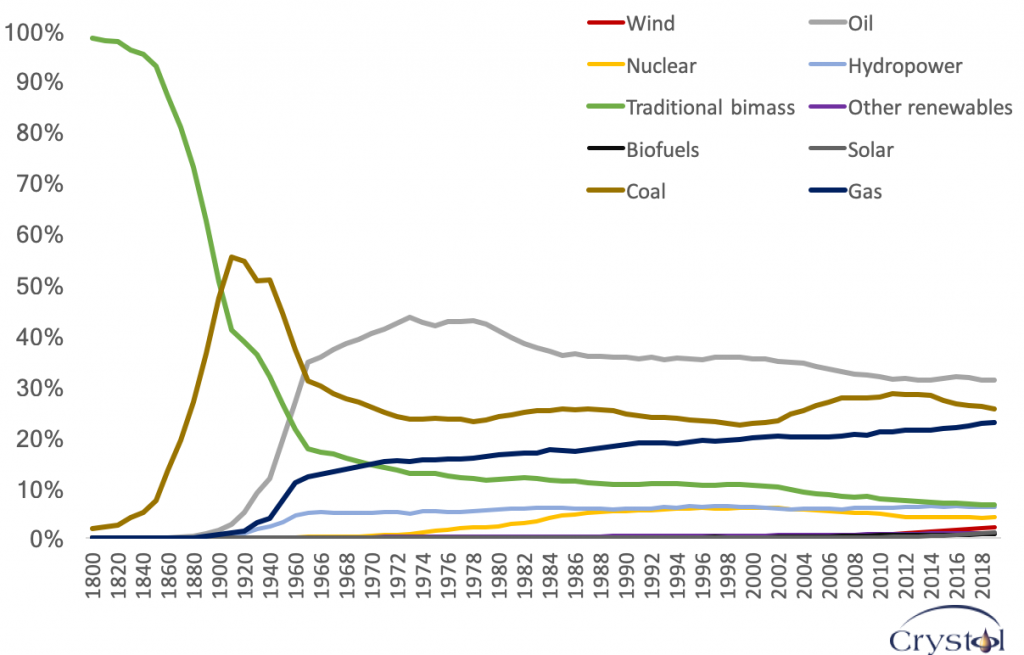

Share of Global Primary Energy Mix, 1800-2019

The story, however, does not end there. Significant and still largely unforeseen effects on our economies, societies, national security and geopolitics will accompany this process – a phenomenon that Dr. Alexander Mirtchev describes in his recent book “The Prologue: The Alternative Energy Megatrend in The Age of Great Power Competition.” Alternative energy developments have coalesced into a 21st-century “megatrend,” the author argues. They have reached a worldwide scope that transcends geographical borders, exerts influence over global actors and broader society, and gained an aura of permanence, he writes.

While the endpoint of this transformation is clear, the process itself is complex and its geopolitical consequences are still not well understood.

Megatrend

The energy transition refers to moving from fossil fuels to a greener future, where renewable and non-carbon-emitting technologies – such as biofuels, solar, wind, hydropower and nuclear power – satisfy most of our energy needs.

However, that is a simple depiction of a very complex, difficult-to-quantify process. It encompasses many facets that span years, even decades. For instance, some say that once a fuel has reached a 25-percent share of the primary energy mix, a transition in dominance has taken place. Although the International Energy Agency (IEA) lists several indicators to track today’s energy transition, from carbon intensity to investment in clean energy, the agency acknowledges that “no single indicator can fully capture the complexity of the global clean energy transition.”

Besides, not all transitions are driven by the same factors. Making historical comparisons is an interesting intellectual exercise but offers limited insight into the future. The rise of coal, the fuel of the Industrial Revolution, was propelled by a complete transformation of products, processes and whole societies. Decades later, oil displaced coal and became the dominant fuel after it became globally available at competitive prices and with superior properties compared to coal.

Today, the clean energy transition is driven not by unique applications or competitiveness, but by a change in preferences. This supports Dr. Mirtchev’s statement that “more than any other phenomena, the alternative energy megatrend could be analyzed as a socially constructed phenomenon,” driven by growing aspirations to protect the environment and human habitat. As a result, the current energy transition requires substantial government involvement to support the quest for a considerably different energy mix.

Security of supply

Currently, green energy is seen as the solution to “a range of energy and economic security concerns, such as the manipulation of energy supplies, commodity price fluctuations, and resource depletion.” Indeed, there is no shortage of commentaries, studies and policies on the security of oil and gas supplies. The United States’ decades-long quest to reduce reliance on Middle Eastern oil and the European Union’s continuous effort to weaken Russia’s grip on its gas supplies are the most prominent examples. There is an entrenched belief that the more a country depends on energy imports to meet its domestic needs, the more vulnerable its supply of energy is. In this respect, since renewable energy such as wind and solar is produced using domestically and widely available resources, security of supply ought to be less of an issue in a greener world.

However, Dr. Mirtchev begs to differ. Although not currently part of national security agendas, the clean energy transition has a security imprint that is immediately felt in sectors such as geopolitics, energy, defense, the environment, and the global economy.

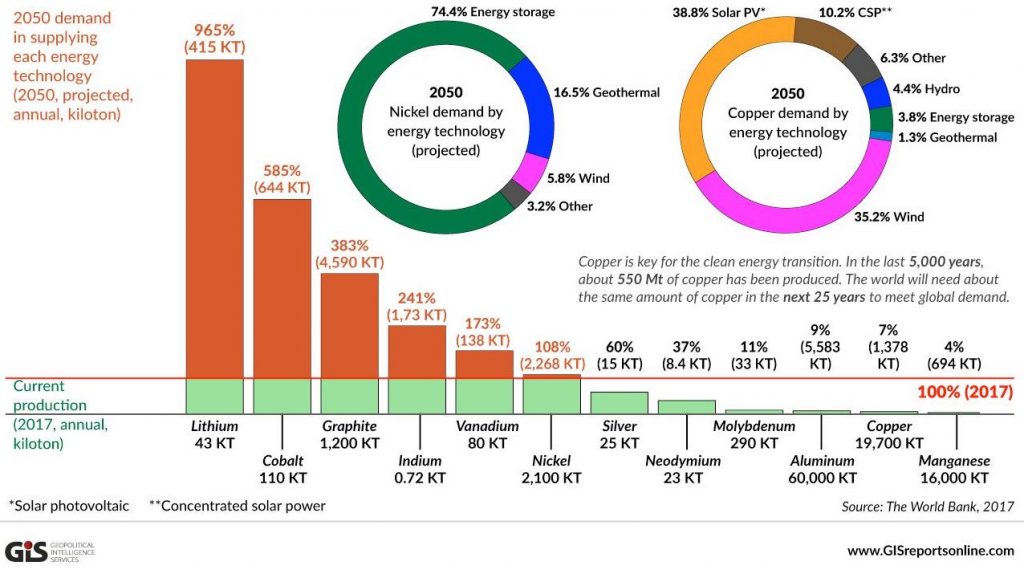

Take, for instance, the World Bank’s studies on the impact of the energy transition on demand for some materials used to produce green energy. According to one such report, “The Growing Role of Minerals for a Low Carbon Future,” if the world is to limit the global temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, demand for metals such as those used in electric storage batteries would grow by more than 1,000 percent. To reach 1.5 degrees – the target recommended by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the growth in demand will be even more dramatic. One can only imagine how expensive such demand increases would make energy, undermining supply security.

Unreliable suppliers

Volume and reliability factors

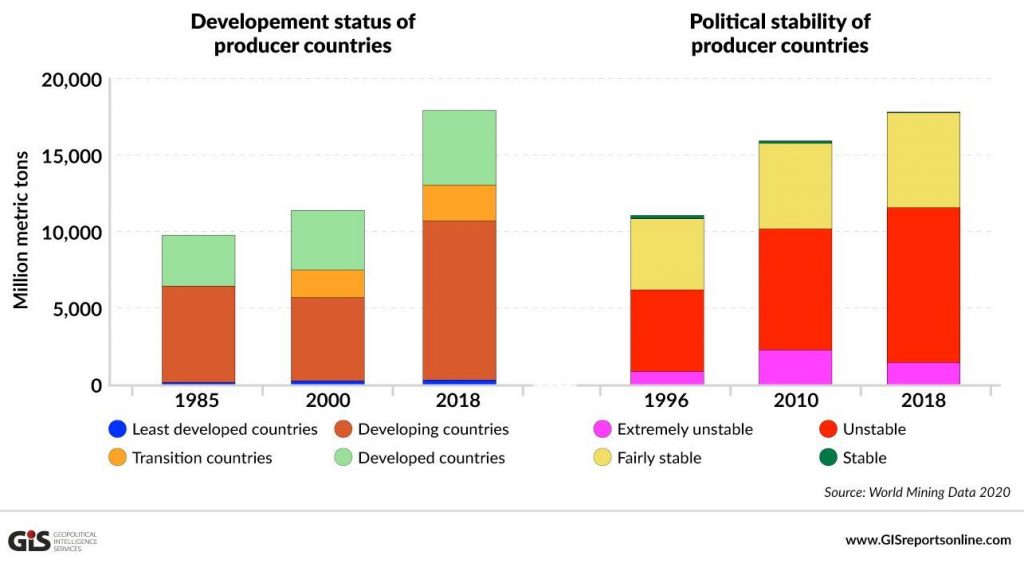

Then there are the other pillars of reliability and sustainability. According to the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism’s “World Mining Data 2020” report, only a small proportion of the metals needed to support the energy transition is produced in countries that qualify as stable. These countries also lack the institutional frameworks to support the sustainable development of the extractives industry.

This reality leads Dr. Mirtchev to argue that “[A]lternative energy developments have intrinsic direct security implications: Alternative energy itself is not simply a referent object that can be securitized, but also a potential source of threats that requires securitization.”

Geopolitical map

One valuable lesson from past energy evolutions and of particular relevance to today’s transition is that every change in the energy source paradigm was accompanied by a shift in who the global hegemon was. Walter Voskuil once observed in a 1942 study on coal and political power in Europe that “only a highly industrialised nation can wage a war on a large scale.” For a long time, energy and politics have been closely intertwined and will likely remain so, no matter what the source of energy is or where it is coming from.

The British Empire was largely built on coal. “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country,” Soviet Russia’s cofounder Vladimir Lenin argued in 1920. And U.S. foreign policy has been greatly influenced by oil – to ensure uninterrupted access to plentiful supplies, which shaped American strategy in the Middle East. The situation changed once the shale revolution unlocked abundant domestic resources and the U.S. became the world’s largest oil and gas producer, overtaking Saudi Arabia and Russia and benefiting from higher oil prices (which it long saw as an economic threat).

In fact, in 2020, the once unthinkable happened: the U.S. brokered a deal between Saudi Arabia and Russia that culminated with the announcement of the OPEC+ deal. Under that agreement, the group cut production by a historic 9.7 million barrels a day, putting a floor under oil prices as the Covid-19 pandemic hit the energy sector severely. “I hated OPEC. You want to know the truth? I hated it. Because it was a fix. But somewhere along the line that broke down and went the opposite way,” U.S. President Donald Trump (2017-2021) said in an interview in 2020, only a few years after he asked, “Why, with all of our own (oil) reserves, we’ve allowed this country to be held hostage by OPEC, the cartel of oil-producing countries, some of which are hostile to America.”

Meanwhile, China, the world’s largest producer of solar, wind and hydro energy – as well as coal – has a shot at global hegemony as it tries to dominate the green energy space, directly and indirectly. The World Bank wrote in a 2017 report, “the most notable finding is the global dominance China enjoys on metals – both base and rare earth – required to supply technologies in a carbon-constrained future.”

In “The Prologue,” Dr. Mirtchev warns that the alternative energy megatrend might lead to unforeseen geopolitical divides based on the new global resource map, ultimately creating tensions over energy-related spaces and geography. But even before the dominance of green energy is fully established and the world finally turns the page on the fossil fuels era, the dynamics at the early stages of the process will also have interesting geopolitical implications.

Demand for metals and minerals in a 2-degree Celsius rise scenario

All forecasting agencies agree that even under the most aggressive climate change policies, the world will continue to use oil and gas for some time. The national oil companies will benefit, particularly in the low-cost-producing Middle East – especially as the private oil companies, mostly in the developed world, expand the share of renewable energy in their portfolio at the expense of hydrocarbons. No wonder the likes of Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) continue to invest heavily in oil and gas with ambitious production capacity expansion targets. These companies and their governments are readying for a fierce competition that will include other important producers, such as the U.S. and Russia.

Middle Eastern oil producers may embrace a “low price high volume” strategy – something they showed the world they could do when they opened the taps in March 2020. Under such a scenario – which is not unlikely, at least not in the early phases of the energy transition – other prominent producers, including the U.S. and Russia, could lose out. But will they simply watch and wait?

With all these moving parts, one can easily indulge in a much deeper and extensive analysis, as Dr. Mirtchev does in the more than 400 pages of “The Prologue.” But even that comes with a sober warning: “the current developments are just a glorious prologue for the things to come. And the things to come are obscured not just by clouds but most probably (and expectedly) far beyond our current visions and imaginations.”

Related Analysis

“The energy transition: Some inconvenient truths“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2021

“Oil in the energy transition age“, Dr Carole Nakhle, May 2020

Related Comments

“International Oil Companies and Energy Transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2021

“OPEC+ Output Decision and the Challenges of Energy Transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2021

“The greening of oil companies“, Dr Carole Nakhle, May 2021