In this exclusive interview with Simon Sarevski from the Austrian Economics Center, Dr Carole Nakhle, CEO of Crystol Energy, discusses the intertwined life between politics and economics of energy and its prospects for the future.

The green transition has made big waves for quite some time now. With the volatility of the green energy sources, the lack of infrastructure at present to support them, and the potential green energy storage problems, to name just a few of the problems green energy is facing, is the green energy transition a pipe dream and if not, in what timeframe can we expect it?

Dr Nakhle: The energy transition is happening and it is not the first time the world has transitioned from the dominance of one fuel to another. However, unlike previous transitions, it is being pushed by changes in preference and not as a result of an industrial revolution for instance (as was the case with coal) or competitive advantage of one fuel over another (as was the case with oil), and that by itself can make it more challenging than previous transitions.

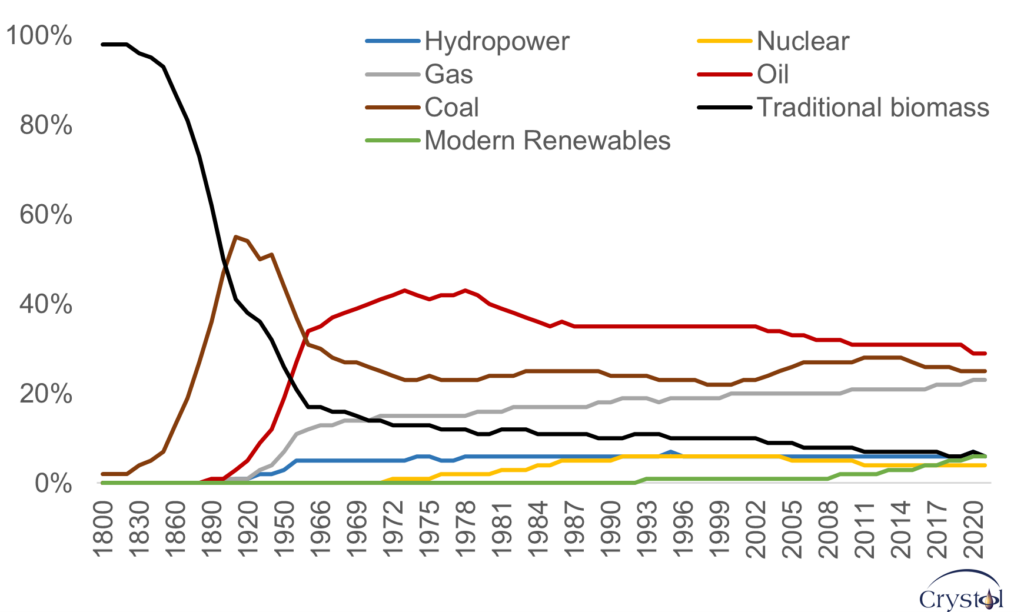

Today, the share of green energy – primarily renewable energy (e.g. solar and wind) in the world’s primary energy mix has been increasing and quite rapidly. However, this is happening from a low base. In 2021, modern renewable energy met 7 percent of the world’s primary energy; hydropower provided an equal share and nuclear 4 percent, but 82 percent is still coming from fossil fuels – that is oil (31 percent), coal (27 percent) and natural gas (24 percent). In this respect, we still have a long way to go for green energy to overtake fossil fuels and for the current energy transition to properly blossom. Arguing otherwise may well be a pipe dream.

How green is the green energy?

Dr Nakhle: We need to agree on what is ‘green’ energy. If it is just about the greenhouse gases emitted during the generation of electricity, then nuclear energy would take the top spot. But nuclear power is highly controversial because of the concerning environmental footprint – from the mining of uranium for instance to storing nuclear waste which remains active for hundreds of years. The mining of minerals and metals used to produce solar panels and wind turbines also has a notable environmental footprint. There are 50 shades of green!

The popularity of electric vehicles is almost unmatched by anything having “green” and “future” in its name. Is all the hype justifiable?

Dr Nakhle: EVs are increasingly popular but their popularity is concentrated in the developed rich economies, though China is the exception in the developing economies. EVs have the potential to end the dominance of oil in the transport sector but they are not quite green. Again, think of the mining of metals and minerals used to produce the batteries, and then the disposal of batteries. Also, one has to look at the source of electricity to charge EVs – is it generated entirely by green energy or by fossil fuels? Then there is an ethical dimension, whereby EVs are a luxury that the majority of people around the world cannot afford, not only because of the cost but also because of lack of access to reliable electricity, and in this respect, they don’t quite meet the basic feature of a ‘just energy transition’ which is ‘leave no one behind’.

What is the future of energy in the short to mid-term? Is it the small modular reactors or green and blue hydrogen or taking a turn back to old technology with huge fixed long-term investment projects or something else entirely?

Dr Nakhle: In the short to mid-term, the world’s primary energy mix is unlikely to look drastically different from what we have today. Technologies such as SMRs and green/blue hydrogen are promising but they are either yet to be proven or their application on a wide commercial scale is yet to happen.

Evolution of the world's energy mix

Data Sources: Our World in Data (based on Vaclav Smil), 2017; BP Statistical Review, 2022

Why do we see nuclear phase-outs and general opposition to nuclear power in some of the developed world?

Dr Nakhle: Nuclear power is probably the most controversial source of energy. On the one hand, it can generate virtually carbon-free electricity at scale, but on the other hand, it comes with a long list of concerns including safety and security, nuclear waste, and major upfront capital requirement. Those concerns have negatively affected the public acceptance of nuclear power, which saw its share of the world’s primary mix peaking in the 1990s and struggling to regain share since.

What role does Germany’s energy policy play in the current energy disaster facing the European Union?

Dr Nakhle: Germany is the largest economy in the EU and the European country with the biggest dependence on Russian energy supplies among its peers – a dependence that has increased until recently, unlike the overall trend in the EU. In 2021, for instance, more than half of Germany’s gas supply came from Russia, and Germany is Russia’s largest gas customer in the EU, accounting for nearly 53 percent of its exports to the Union. Russia’s exports to the EU are primarily by pipeline, with two major pipelines Nord Stream 1 (under the Baltic Sea to Germany) and Yamal (to Poland and Germany via Belarus) crossing the German territory, in addition to Nord Stream 2, a replica of Nord Stream 1 (both in terms of route and capacity). In that respect, one can argue that through Germany, Russia maintained a strong grip on the European gas market in particular, as Germany pursued its own economic interests.

However, the ‘special’ long-standing relationship between Germany and Russia has been broken following the war in Ukraine and we have seen Germany taking an unusually tough stance on Russia, starting with canceling the certification of Nord Stream 2 to openly describing Russia as an unreliable supplier and supporting EU sanctions on Russia.

As gas to the EU is shot down from the east, can the EU rely on North America for its LNG needs? Moreover, is it only a question of politics and energy availability or infrastructure and investment? After all, the energy has to reach Central and Eastern Europe somehow, doesn’t it?

Dr Nakhle: The EU should not rely on any single supplier irrespective of where the supplies are coming from. After all the basic pillar of energy security is diversity and diversity alone. North American LNG has surely helped in reducing the impact of the loss of Russian gas but so has Norwegian gas as well as gas coming from North Africa and the Middle East, among others. The EU should support the expansion of its gas import infrastructure while sending a consistent signal to investors and gas exporters alike that their market will be secured for years to come, and not just that their gas is wanted only as a ‘temporary’ solution to help the EU go through the crisis this winter.

Finally, although not directly related to the general topic of today’s conversation, I would like to end the interview with this: How to find freedom in an unfree world?

Dr Nakhle: Speak honestly, speak loudly, speak constantly, support like-minded friends, and be patient. The great castles of suppression will sooner or later be undermined.

Related Analysis

“Germany’s scramble to revamp its energy policy“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2022

“Thatcher’s energy plan was derailed – now we are paying a gigantic price“, Lord Howell, Sep 2022

“Energy policy confusion“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2022

Related Comments

“How did Europe arrive to the current energy crisis?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Oct 2022

“European gas crunch, African supply and the energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Sep 2022