Dr Carole Nakhle

The war in Ukraine has redefined many countries’ energy priorities, given its repercussions on energy security and import dependency. Less than two months following Russia’s invasion, the United Kingdom published a policy paper entitled “British energy security strategy,” which states how the country will accelerate “homegrown power for greater energy independence.” Not surprisingly, the host country of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference has placed a particular focus on renewable energy and nuclear power. However, equally interesting was the explicit recognition of the role domestic oil and gas resources, especially the North Sea energy fields, play in terms of energy security and climate agenda.

Not-so-surprising turn

“We’re going to make better use of the oil and gas in our own backyard by giving the energy fields of the North Sea a new lease of life,” British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said.

Around the same time, Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Kwasi Kwarteng sent a letter to the oil and gas industry bluntly stating, “we will not bend to the will of activists who naively want us to extinguish production in the UK Continental Shelf – doing so would put energy security and British jobs at risk, and simply increases foreign imports, whilst not reducing demand.” The business secretary further reiterated the government’s support for more investment “to accelerate and maximise domestic oil and gas production… to protect the North Sea as a major UK energy asset for decades to come.”

This puts the UK on a collision course with climate activists who have been calling for halting oil and gas exploration. Only a year ago, the International Energy Agency (IEA) argued in its flagship “Net Zero 2050” report that “there is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply in our net zero pathway … beyond projects already committed as of 2021.”

However, the UK’s latest energy strategy sensibly attempts to balance energy and climate security. It also recognizes the vital role of its oil and gas industry in ensuring secure energy supplies throughout the transition and in accelerating that transition by building on the industry’s expertise, capital and infrastructure. This is no easy task but is undoubtedly a more pragmatic approach to the energy transition.

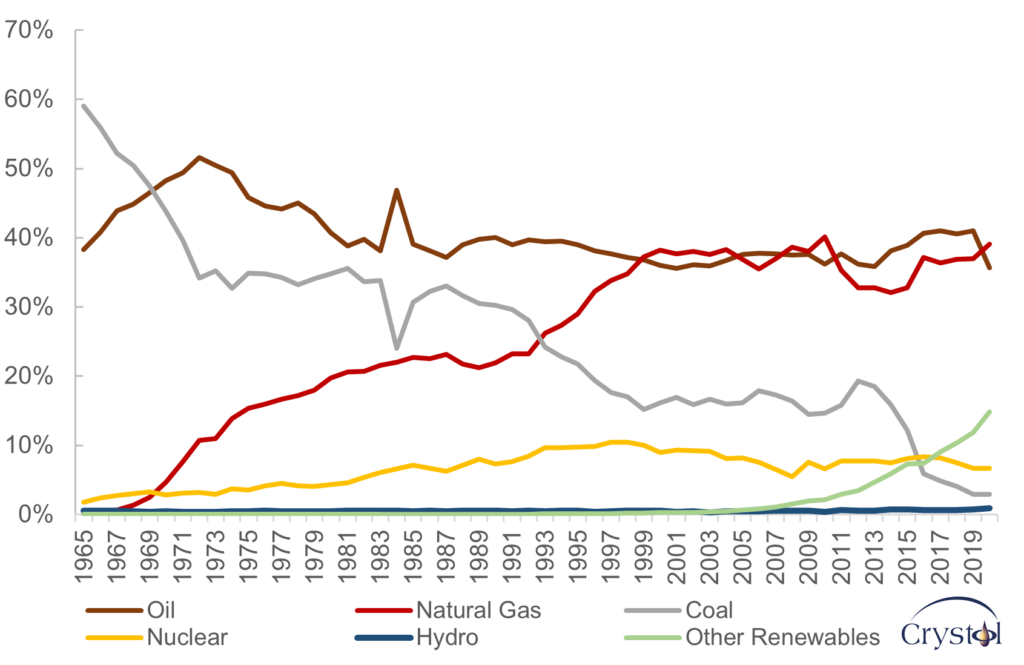

Evolution of the UK’s energy mix

Data Source: BP, 2021

Evolution

The UK’s energy mix has fundamentally shifted since 1965.

Coal, which was once the dominant fuel and powered Britain’s industrial revolution, has almost vanished from the country’s energy and electricity mix, with shares of 3 percent and 2 percent respectively – the lowest among the world’s largest economies. In power generation, coal’s share has been primarily replaced by natural gas, supported by production from the North Sea and renewable energy, and deployed at a fast rate since the late 2000s.

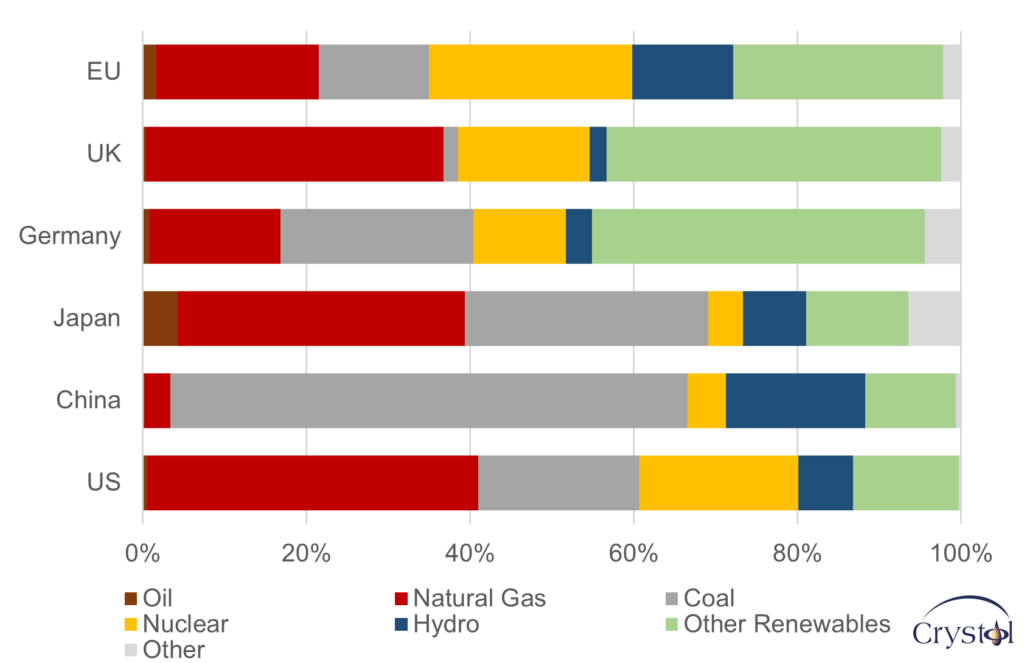

Today, the UK has the highest share of renewable energy (41 percent) in electricity generation among the world’s 10 richest economies. Although Germany has a similar percentage, coal still fuels 24 percent of that country’s electricity generation.

Electricity mix in the EU and the world’s five largest economies, 2020

Data Source: BP, 2021

Oil and gas continue to play an important role; together, they account for nearly three-quarters of the UK’s energy mix. The discovery of sizable volumes of hydrocarbons under the waters of the North Sea in the mid-1960s provided the impetus for their wider deployment domestically.

From an energy security perspective, the importance of these resources became particularly notable after the first oil shock in 1973, when the Arab producers within OPEC cut their supplies in retaliation for the West’s support of Israel in its war against Egypt. While British consumers were still exposed to the rise in oil prices following the shock, those prices boosted developments in the North Sea, which, back then, was considered a frontier area for oil and gas exploration and production. That investment later translated into higher production, contributing to the dilution of OPEC’s power over global oil markets.

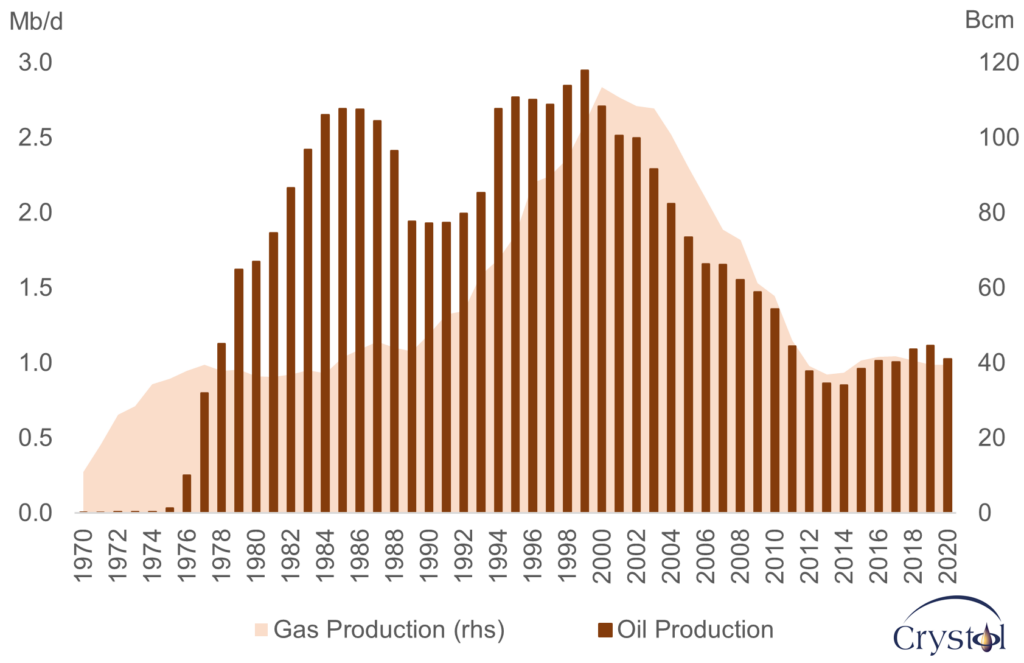

By 1999 – when oil production hit its maximum level – the UK was the world’s ninth-largest oil producer (after Saudi Arabia, the United States, Russia, Iran, Mexico, China, Norway and Venezuela). At 2.9 million barrels a day (mb/d), the UK produced more oil than most OPEC producers, with only Saudi Arabia (8.5 mb/d) and Venezuela (3 mb/d) pumping more.

Gas production also grew at a remarkable pace. At its peak in 2000 of more than 113 billion cubic meters (bcm), the UK was the world’s fourth-largest gas producer, after Russia, the U.S. and Canada.

UK oil & gas production

Data Source: BP, 2021

Energy security

Since hitting the peak, the UK’s oil and gas production has been declining, as the discovery and development of new reserves failed to keep pace with the maturation of existing fields.

Still, the UK remains a sizable oil and gas producer. Although it currently ranks 18 in the world for both oil and gas production, its oil output has been in the range of 0.8 to 1.1 mb/d in the last five years. Currently, the UK’s oil output is similar to Oman’s but outpaces Oman in gas production.

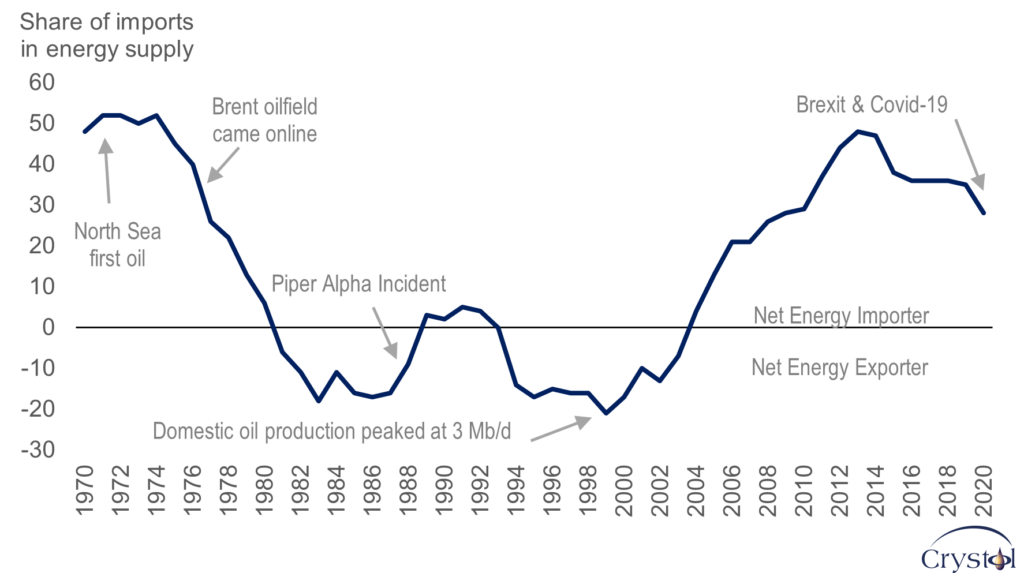

The decline in production has reversed the UK’s status from a net exporter to a net importer of both fuels. Oil and gas imports have increased consequently, and the growing dependence on imports has raised fresh concerns about energy security. However, the UK is still better placed than many countries in Europe when it comes to this issue.

UK energy import dependency

Data Source: Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, UK

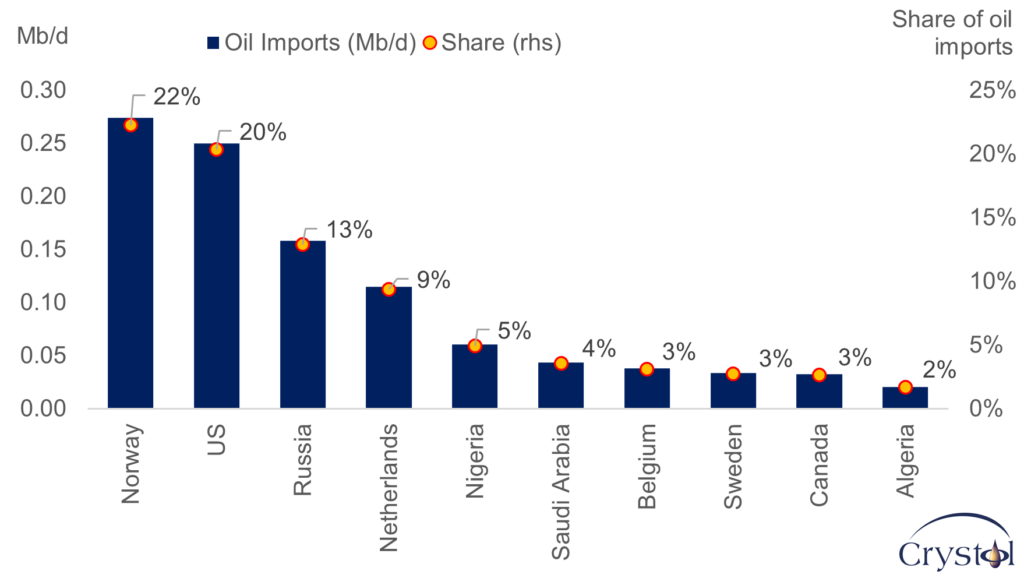

Despite its maturity, the North Sea still meets 83 percent and 54 percent of domestic oil and gas needs, respectively. Imports meet the rest, but the UK’s sources of supplies are well-diversified. For both oil and gas, Norway is the largest supplier (22 percent of oil imports and 55 percent of gas by pipeline), followed by the U.S. (20 percent) for oil and Qatar (20 percent via liquefied natural gas, LNG) for natural gas. Russia is the third-largest supplier of oil to the UK, providing around 13 percent of the country’s oil imports (160,000 barrels per day).

For gas, Russia ranks fourth (after the U.S., which provides 11 percent via LNG), but its exports represent only five percent of the UK’s gas import needs. In this respect, the UK is not as exposed to Russia as many EU countries. This explains why in March this year, the UK was swift to announce that it would phase out Russian oil imports by the end of 2022.

Major UK oil suppliers

Data Source: Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, UK

Bridging the gap

The UK has committed to net-zero emissions by 2050. This may seem a very ambitious goal for an established oil and gas producer keen on safeguarding its hydrocarbons industry. However, apart from its contribution to energy security, both the government and the industry see the North Sea as central in the energy transition. “There is no contradiction between our commitment to net zero and our commitment to a strong and evolving North Sea industry. Indeed, one depends on the other,” the government stated.

The North Sea has many features that support the energy transition. Apart from the fact that domestic production has a lower carbon footprint than imported energy, the extensive availability of infrastructure can be used to deploy offshore wind, for instance. The North Sea’s depleted oil and gas fields and empty caverns can be used to store carbon dioxide through Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology. The industry’s vast expertise can be deployed to spur the production of hydrogen.

The ongoing cooperation between the government and the industry and the competitive market structure has been central to tackling the country’s and the sector’s challenges. In 2021, the government published the North Sea Transition Deal, the first of its kind globally, which builds on that partnership to support the decarbonization of oil and gas. In response to the deal, the industry has committed to a gradual reduction in production emissions in the coming years to achieve a net-zero basin by 2050.

The UK’s latest approach to the energy transition will not appeal to everyone, but it is undoubtedly grounded in pragmatism and is an avenue worth pursuing.

Facts & Figures

- The UK economy is the fifth-largest in the world after the U.S., China, Japan and Germany.

- Based on the current production forecast, the UK’s oil and gas reserves could sustain production from the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) for another 20 years or more.

- In 2020, 28% of the UK’s energy needs were met by imports.

- Britain’s electricity mix relies on 38% of fossil fuels, mostly gas.

- By 2030, the government aims to have 95% of the country’s electricity generation from low-carbon sources.

- The oil and gas industry has committed to a series of targets to drive down emissions to achieve cleaner production: 10% by 2025; 25% by 2027; 50% by 2030; and a fully net-zero basin by 2050.

- The UKCS is home to around 290 offshore installations, over 10,000 km of pipelines, 15 onshore terminals and over 2,500 wells. It supports around 147,000 jobs directly and in the supply chain.

Related Analysis

“Energy Markets and the Design of Sanctions on Russia“, Christof Rühl, Mar 2022

“An Energy Crisis Like No Other“, Lord Howell, Oct 2021

“Trying to grasp the geopolitics of the energy transition“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Sep 2021

“The energy transition: Some inconvenient truths“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2021

Related Comments

“A changing global energy map“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2022