Dr Carole Nakhle

Despite the prevailing sentiment of energy scarcity in Europe, there is no actual shortage of gas resources, including at the European Union’s doorstep. However, developing those resources and expanding the capital-intensive infrastructure to bring them to market will take time – and, more importantly, require producers to be confident that demand will be there for years to come.

This is the argument Norway – the EU’s second-largest oil and gas supplier after Russia – has made for years and recently reiterated. “If Europe commits to buying, Norway can replace more Russian gas,” its Minister of Petroleum and Energy Terje Aasland said in May.

One month later, on June 23, the EU and Norway announced they would be “strengthening energy cooperation.” The statement’s emphasis on the long term was striking, as was its support for future resource exploration. “Recognizing that Norway has significant remaining oil and gas resources and can, through continued exploration, new discoveries and field developments, continue to be a large supplier to Europe also in the longer term beyond 2030,” the joint statement read. “The EU supports Norway’s continued exploration and investments to bring oil and gas to the European market.”

Like any producer, Norway seeks to secure demand for its exports, which has made it one of the richest countries in the world and helped Europe reduce its dependence on Russian energy. The EU-Norway cooperation statement will buttress Norway’s continued access to its most important market.

On the supply side, local opposition to further exploitation of the country’s hydrocarbon resources has also posed a challenge. But, to the dismay of climate activists, the EU cooperation agreement gives the Norwegian oil and gas industries backing to pursue investment and expand both production and exports.

Model supplier

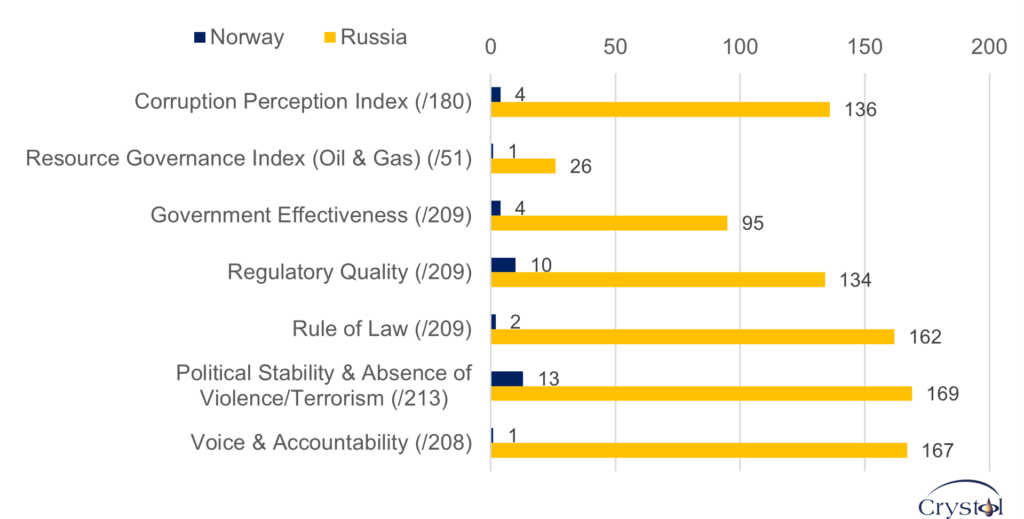

Norway is a remarkable oil and gas producer, outperforming its peers on nearly all governance indicators, particularly energy-related. When compared to Russia, the two countries find themselves on opposite ends of the governance spectrum.

Norway and Russia, selected governance indicators (ranked from 1, descending)

Data Sources: Transparency International, World Bank, Natural Resource Governance Institute

Since oil and gas production began in the North Sea in 1971, Norway has been the most reliable external supplier for the world and Europe.

Although its proven oil and gas reserves globally rank only 17 and 20, respectively, Norway is the world’s 11th and ninth producer of oil and gas – slightly ahead of Mexico for oil and almost on par with Saudi Arabia for gas. Thanks to its small local market and a heavy reliance on hydropower, which meets more than 92 percent of domestic electricity needs, Norway can export nearly all the oil and gas it produces.

As a result, the Nordic country is the world’s seventh-largest oil exporter – after Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States – and is the fourth largest gas exporter, after Russia, the U.S. and Qatar. Norwegian energy exports are not exposed to the same risk facing exporters such as Algeria and Egypt, namely the rapid growth in domestic consumption that has limited their export potential.

Norway has been exemplary in managing its oil and gas revenues. Its Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) is the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund – even though it is several decades younger than funds such as those of the UAE or Kuwait, and despite the fact that Norway is a smaller oil producer than those countries. The Norwegian economy is also less exposed to the vagaries of oil and gas price volatility than many other producers.

Norway is also a climate-conscious producer of hydrocarbons. In 1991, it became one of the first countries to introduce a carbon tax, at a rate now among the world’s highest. Investment in renewable energy infrastructure is also one of the four key investment areas (alongside equities, bonds and real estate) for the GPFG.

Exports to Europe

Although not a member state, Norway has a close relationship with the EU through the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement and several other bilateral deals. The EU and Norway also enjoy active cooperation on foreign and security policy issues – part of a partnership based on “shared fundamental values and underpinned by our common heritage and history, as well as strong cultural and geographical ties,” as the EU puts it.

These factors help give Norway a clear advantage over other producers that the EU is turning to in order to reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas. Given the geographic proximity, Europe is a strategic market for Norwegian oil and gas, accounting for around 71 percent of Norway’s oil exports and nearly 100 percent of its gas exports in 2021.

The reach of Norwegian gas has been typically concentrated in Western Europe, transiting primarily via pipelines. Five gas pipelines connect the Nordic country to continental Europe, and two stretch to the United Kingdom, with a combined export capacity of more than 131 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year.

Gas pipelines connecting Norway to Europe

However, with the Baltic Pipe now under construction, which will send gas to Poland via Denmark, Norway has stepped onto the traditional “territory” of Russia, whose gas exports to Europe are concentrated in Central and Southeast Europe. The project is expected to deliver 10 bcm of gas annually to Poland, meeting nearly half of the country’s total consumption. The pipeline is set to be fully operational from October 2022, helping alleviate the blow caused by Russia cutting its gas supplies to Poland in April this year.

Norway also exports liquefied natural gas (LNG) but is a minor player in this market segment, accounting for less than 1 percent of global LNG trade, with 95 percent of its LNG sales heading to Europe due to the short distance.

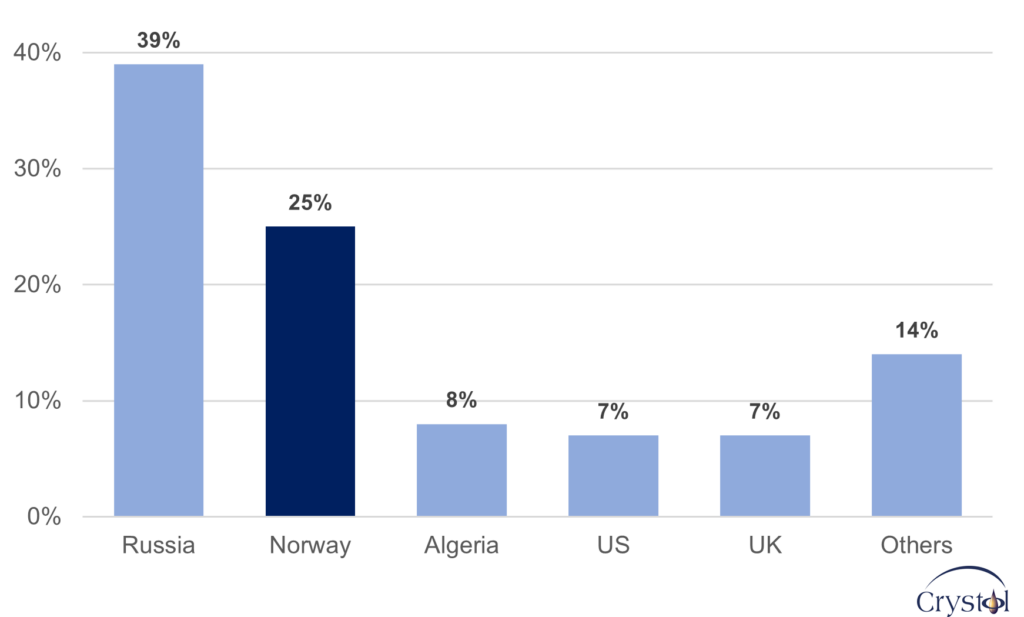

In total, Norway accounts for 25 percent of the EU’s gas imports. Although it trails Russia, which dominates the market with a share of 39 percent, Norway dwarfs other suppliers. Algeria, the third-largest gas supplier to Europe, accounts for only 8 percent. In this respect, Norway has been Russia’s main competitor in Europe and will not hesitate to grow its presence in the market. The question is whether it has the capacity to expand its footprint much more.

EU gas imports by source, 2021

Data Source: Eurostat

Untapped resources

Norway claims to have the resources to send more gas to Europe. It has been able to deliver additional volumes of gas to Europe at short notice after Russia invaded Ukraine and gradually cut its supplies. The Norwegians took temporary measures like delaying maintenance and increasing gas production permits in certain fields. But Norway is currently producing and exporting at near full capacity, and further increases in exports will need to be supported by more significant output growth.

Norwegian authorities expect oil and gas production to continue to increase until 2024 and decline afterward. However, the longer-term decline can be reversed or decelerated should large discoveries be made – and the potential seems to be there. To date, only a third of the country’s gas resources have been produced and sold, with two-thirds of expected natural gas resources yet to be exploited.

Still, not all those resources have been discovered or proven technically and commercially exploitable. And the remaining sizeable resources seem to be located in the least explored seas of the Norwegian shelf, namely the Norwegian and Barents Seas. The North Sea has been the powerhouse of Norway’s oil and gas exploration and production for decades, and the government expects most discoveries in that area to be relatively small. In contrast, the northern part of the Barents Sea has the greatest likelihood of significant discoveries on the Norwegian shelf.

Apart from technical challenges, including a lack of infrastructure, exploring the pristine Arctic waters has long been a critical issue – aggravated in recent years by concerns over climate change. In 2021, for instance, climate activists sued the Norwegian government on the grounds that oil and gas licensing permits given in the Barents Sea threatened their right to a clean environment under the country’s constitution. More recently, the environmental group Friends of the Earth Norway has argued that Europe’s current energy situation does not justify more oil and gas exploration. At the same time, the opposition Socialist Left Party described an increase in such activity as an environmental mistake. Opening up those areas for further exploration will only attract more hostility.

Norway certainly has the potential to play a more prominent role in the European gas market. However, how big that role will be depends on the government’s ability to balance its economic and strategic interests and an ambitious climate change agenda. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have tilted the scales in favor of the former. The EU’s latest energy cooperation agreement gives strong backing to Norway’s oil and gas industry.

Facts & Figures

- At 67%, the Norwegian state is the main shareholder in Equinor, the largest gas producer on the Norwegian continental shelf and the second-largest gas supplier in Europe after Gazprom.

- Norway ranks 52 and 60 in the world for oil and gas consumption, respectively.

- The GPFG is a long-term investor in around 9,000 companies in 70 countries.

- Norway has two LNG export plants: Snohvit LNG, with an export capacity of 6.6 bcm per year, and Nordic LNG, with export capacity of 0.4 bcm year.

- In 2021, Norway exported around 115 bcm of gas to Europe, with Germany (43%) and the UK (29%) the biggest recipients, followed by France (15%) and Belgium (13%), according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

- Gas sales from Norway are expected to rise by 8% in 2022.

- There are 71 producing fields in the North Sea, compared to 21 in the Norwegian Sea and only two in the Barents Sea.

Related Analysis

“Russia’s oil is in long-term decline – and the war has only added to the problem“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2022

“Kazakhstan: An energy opportunity for the EU“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2022

Related Comments

“Record profits for oil-producers“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Aug 2022

“Russia’s war help Qatar reassert its importance“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jul 2022

“Could Iran and Venezuela Help Biden’s Gas Crisis?“, Dr Carole Nakhle, Jun 2022

“Europe looks to Africa for energy security“, Dr Carole Nakhle, May 2022